H.C.F. Mansilla, Los Tiempos:

This slogan, chanted in a modest public demonstration on October 25, 2023 by urban youth groups, represents one of the few testimonies of sociopolitical rationality that has been heard in recent times. The expression refers equally to traditional peasant groups and modern private entrepreneurs as those responsible for forest fires. Irrationality—the country’s collective mentality—expands and affects almost all social sectors. This makes any serious initiative to avoid ecological disasters in Bolivia very difficult.

Mass education, the majority of the media and family practices are not favorable to rational regulations, such as the consideration of the long term, the protection of the environment, pluralistic democracy, the effective validity of human rights, the fight against corruption and public discussion of programmatic options.

The vast majority of the Bolivian nation is, of course, not an explicit supporter of forest fires or authoritarianism in socio-political life. But implicitly the general mentality of Bolivian society is not favorable to the preservation of the environment nor to a pluralistic democracy. The pro-ecological potential, therefore, remains very low, because disinterest in the long term, disdain for political rationalism and the cult of collective feelings and emotions remain predominant. This is clearly perceived in the lack of understanding of abstract concepts such as the conservation of the tropical forest so that in the future, that is, in the long term, it continues to be a strong determinant of atmospheric humidity and oxygen.

Some details of this topic can be clarified by mentioning recurring phenomena in the Andean region. Next to the grandeur of the landscape of the high mountains is the flatness of human work: the majestic mountain range as a backdrop and the plastic garbage announcing the proximity of urban settlements. The most serious thing lies in the fact that no one is aware of this realm of ugliness: neither the social movements, nor the political parties, nor the progressive intellectuals, nor the small liberal groups that have emerged lately.

The majority of Bolivians, regardless of their geographical, social or ethnic origin, are routine and conventional in their daily life and in their values orientation, but they are not conservationists in the ecological sense: they do not take convenient and effective care of the vulnerable soils. and landscapes and rather devotes itself to destroying nature.

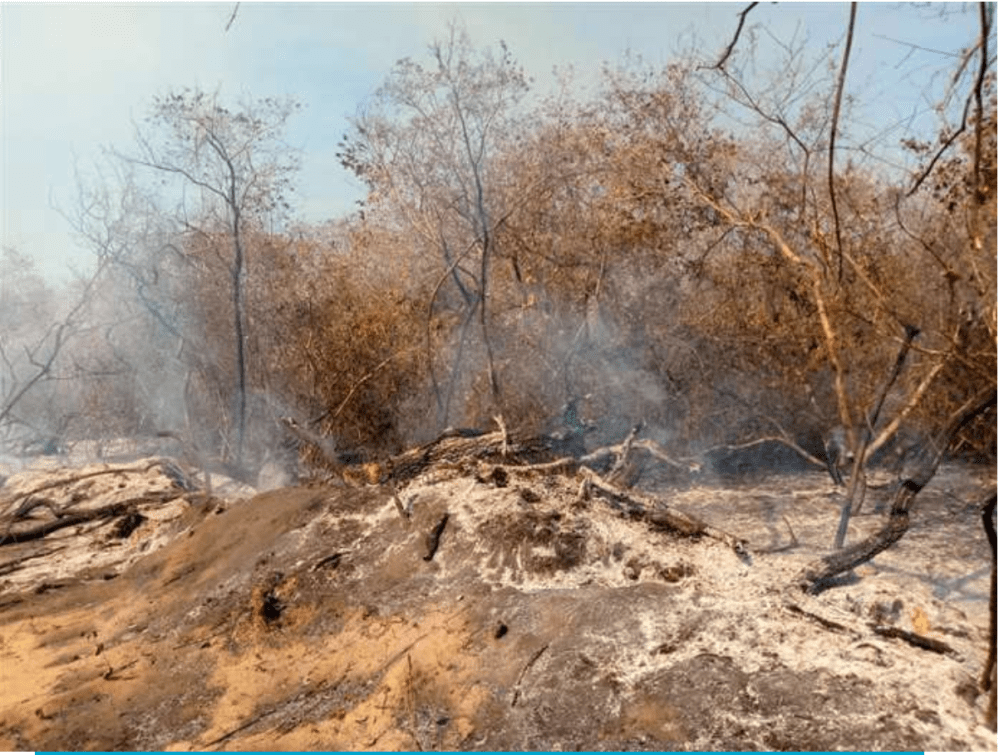

Almost all social groups contribute, sometimes without suspecting it, to a true environmental catastrophe. They try, for example, to expand the agricultural frontier by burning the vegetation cover in tropical regions, which according to them means bringing progress to the jungle. For several years now, immense fires have been occurring in eastern Bolivia, burning millions of hectares annually. Almost no one cares. For example: no political party, no Indianist intellectual, no indigenous organization, no representation of peasant interests, but also no university institution and no business union, shows indignation or initiates a slight protest at this phenomenon, induced by the hand of human beings to expand the agricultural frontier.

The general result that can be verified empirically is deplorable: forests burned, surfaces cleared, land eroded. In a word: the death of nature lurking at every step. Prosperous businessmen and modest workers are equally responsible for this disaster. Disaster? In reality, everyone is happy—except for some marginal farmers directly affected by the fire and some sensitive people in urban centers—because now the land can be used much more profitably and easily. Everywhere a surface cleared by fire is economically much more valuable than one still covered by uncomfortable jungle.

In the specific case of tropical soils, the following can be stated, for which I base myself on works that have appeared in the last four decades, works that have not lost their explanatory effectiveness and that very early pointed out the seriousness of the ecological situation. In Peru and Bolivia we must mention the peasants dedicated to the cultivation of coca and the production of cocaine, who contribute on a large scale to the expansion of the agricultural frontier. Other sectors, such as colonizers, farmers, ranchers, soybeans, timber businessmen, subsistence workers and searchers for gold and valuable minerals in tropical rivers, also do their part in reducing forests in the lowlands. In short: it is difficult to find a social sector that does not lend its help to the progressive elimination of tropical forests.

The ecological crisis also affects colonizers from highlands who try to find a new existence in the humid areas of the Amazon. According to the very early testimony of Wagner Terrazas Urquidi (1973), tropical soils are highly vulnerable because they generally contain a very thin and fragile layer of humus, which deteriorates irretrievably after the original plant cover is destroyed. Faced with the relatively rapid depletion of the productivity of tropical soils and the emergence of eroded surfaces, colonizers, coca growers, soybean growers and loggers, among other sectors, are forced to constantly search for new cultivation areas and to constantly expand the agricultural frontier.

Soon and in the face of public indifference, the rainforest will be a mere literary memory.

Esta consigna, coreada en una modesta manifestación pública el 25 de octubre de 2023 por grupos juveniles urbanos, representa uno de los pocos testimonios de racionalidad sociopolítica que se ha escuchado en los últimos tiempos. La expresión alude por igual a grupos campesinos tradicionales y a empresarios privados modernos como los responsables de los incendios forestales. La irracionalidad —la mentalidad colectiva del país— se expande y afecta a casi todos los sectores sociales. Esto hace muy difícil cualquier iniciativa seria para evitar desastres ecológicos en Bolivia.

La educación masiva, la mayoría de los medios de comunicación y las prácticas familiares no son favorables a normativas racionales, como la consideración del largo plazo, la protección del medio ambiente, la democracia pluralista, la vigencia efectiva de los derechos humanos, la lucha contra la corrupción y la discusión pública de opciones programáticas.

La inmensa mayoría de la nación boliviana no es, por supuesto, partidaria explícita de los incendios forestales ni del autoritarismo en la vida sociopolítica. Pero implícitamente la mentalidad general de la sociedad boliviana no es favorable a la preservación del medio ambiente ni tampoco a una democracia pluralista. El potencial proecológico, por lo tanto, sigue siendo muy bajo, porque el desinterés por el largo plazo, el desdén por el racionalismo político y el culto de los sentimientos y las emociones colectivas permanecen como predominantes. Esto se percibe claramente en la incomprensión de concepciones abstractas como la conservación del bosque tropical para que en el futuro, es decir a largo plazo, siga siendo una fuerte determinante de la humedad y del oxígeno atmosféricos.

Algunos detalles de esta temática se pueden aclarar mencionando fenómenos recurrentes en la región andina. Al lado de la grandiosidad del paisaje de las altas montañas se halla la chatura de la obra humana: la majestuosa cordillera como telón de fondo y la basura plástica anunciando la proximidad de los asentamientos urbanos. Lo más grave reside en el hecho de que nadie es consciente de este reino de la fealdad: ni los movimientos sociales, ni los partidos políticos, ni los intelectuales progresistas, y tampoco los pequeños grupos liberales que han surgido últimamente.

La mayoría de los bolivianos, independientemente de su origen geográfico, social o étnico, es rutinaria y convencional en su vida cotidiana y en sus valores de orientación, pero no es conservacionista en la acepción ecológica: no cuida de manera conveniente y efectiva los vulnerables suelos y paisajes y más bien se consagra a destruir la naturaleza.

Casi todos los grupos sociales contribuyen, a veces sin sospecharlo, a una verdadera catástrofe medioambiental. Tratan, por ejemplo, de ensanchar la frontera agrícola incendiando el manto vegetal en las regiones tropicales, lo que significa según ellos llevar el progreso a la selva. Desde hace ya varios años ocurren inmensos incendios en el Oriente boliviano, ardiendo anualmente millones de hectáreas. A casi nadie le importa. Por ejemplo: ningún partido político, ningún intelectual indianista, ninguna organización indigenista, ninguna representación de intereses campesinos, pero tampoco ninguna institución universitaria y ningún gremio empresarial, muestra indignación o inicia una leve protesta por este fenómeno, inducido por la mano del ser humano para ampliar la frontera agrícola.

El resultado general que se puede constatar empíricamente es deplorable: bosques incendiados, superficies taladas, terrenos erosionados. En una palabra: la muerte de la naturaleza rondando a cada paso. Prósperos empresarios y trabajadores modestos son por igual responsables de este desastre. ¿Desastre? En realidad, todos están contentos —salvo algunos cultivadores marginales afectados directamente por el incendio y alguna gente sensible en los centros urbanos—, pues ahora el terreno puede ser utilizado de manera mucho más rentable y fácil. En todas partes una superficie desboscada por el fuego es económicamente mucho más valiosa que una cubierta aún por la incómoda selva.

En el caso específico de los suelos tropicales se puede aseverar lo siguiente, para lo que me baso en obras aparecidas en las últimas cuatro décadas, obras que no han perdido su eficacia explicativa y que muy tempranamente señalaron la gravedad de la situación ecológica. En Perú y Bolivia hay que mencionar a los campesinos consagrados al cultivo de la coca y a la elaboración de cocaína, los cuales coadyuvan en gran escala a la expansión de la frontera agrícola. Otros sectores, como los colonizadores, los agricultores, los ganaderos, los soyeros, los empresarios de la madera, los trabajadores de subsistencia y los buscadores de oro y minerales valiosos en ríos tropicales, hacen también su parte en la reducción de las arboledas en las tierras bajas. En suma: es difícil encontrar un sector social que no preste su ayuda a la progresiva eliminación de los bosques tropicales.

La crisis ecológica también toca a los colonizadores provenientes de tierras altas que tratan de encontrar una nueva existencia en las zonas húmedas de la Amazonía. Según el testimonio muy temprano de Wagner Terrazas Urquidi (1973), los suelos tropicales son altamente vulnerables por contener generalmente una capa de humus muy delgada y frágil, que se deteriora de manera irremisible después de que se destruye la cubierta vegetal original. Ante el agotamiento relativamente rápido de la productividad de los suelos tropicales y el surgimiento de superficies erosionadas, los colonizadores, los cocaleros, los soyeros y los madereros, entre otros sectores, están obligados a buscar constantemente nuevas áreas de cultivo y a ampliar sin cesar la frontera agrícola.

Dentro de poco y ante la indiferencia pública, la selva tropical será un mero recuerdo literario.

https://www.lostiempos.com/actualidad/opinion/20231027/columna/ni-coca-ni-soya-bosque-no-se-toca