Tatiana Castro, Los Tiempos:

Park Rangers Must Face Harassment from Encroachers and Illegal Miners

Park ranger Marcos Uzquiano patrols a protected area. | Courtesy of park rangers

Park ranger Marcos Uzquiano patrols a protected area. | Courtesy of park rangers A park ranger reports on illegal constructions in Tunari.

A park ranger reports on illegal constructions in Tunari.

Park rangers must confront the lack of human resources, adverse working conditions, harassment from encroachers, and judicial harassment in their tasks of protecting the 23 parks and protected areas in Bolivia. They feel defenseless and unauthorized.

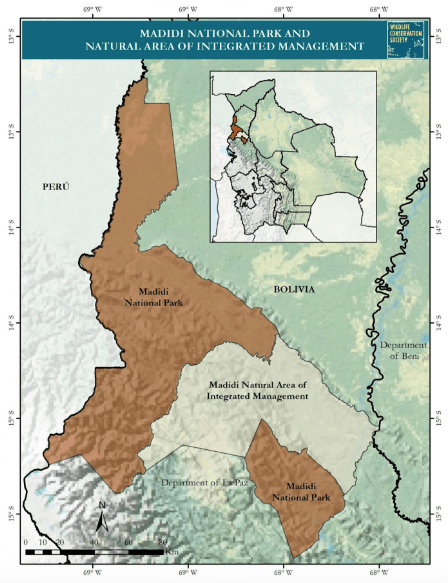

The vice president of the Bolivian Association of Park Rangers Conservation Agents (Abolac), Jimmy Torrez Muñoz, warns that in Madidi National Park, the most serious problem is the presence of illegal mining in the rivers.

Park rangers Marcos Uzquiano, who currently holds the position of president of Abolac, and Raúl Santa Cruz are an example of the harassment that exists from mining companies engaged in illegal exploitation in the parks of eastern Bolivia; both face a trial for denouncing the aggressions of a businessman when he was transporting heavy machinery into Madidi National Park “by force and without any authorization.”

The problem is more serious because they also do not have the necessary support from the administrators of the National Service of Protected Areas (Sernap), which preferred to step aside from the litigation, despite the fact that the conflict arose in the performance of their work. “We haven’t even received a supportive call,” laments Uzquiano.

On the subject, the executive director of Sernap, Johnson Jiménez, clarified that it is a private process. Therefore, they cannot get involved.

Torrez mentions that in other parks such as the Protected Area of Toro Toro National Park, in Potosí, the most serious conflict is with land encroachers.

Park rangers are carrying out a judicial process for the occupation of about 2 hectares of land, and despite the “dispossession and eviction” mandate, the encroachers have not been removed. Instead, they are victims of intimidation and threats through resolution votes asking for their dismissal. From Sernap, in this case, support was given to the “protection body” of Toro Toro National Park.

Torres mentions that in Tunari National Park, where he currently works, the problem of aggregate exploitation and intimidation by encroachers who want to take over land above the 2,750-meter mark is added. “Many times we have been kidnapped and even threatened with the burning of our cars,” recalls the park ranger.

All park rangers must face the violence of groups of encroachers who want to settle in protected areas, Torres points out.

Another problem is that there are very few of them to cover thousands of hectares. In the case of Tunari National Park, there are eight to monitor an area of 300,000 hectares, and, in the case of the Biosphere Reserve and Biological Station of Beni, there are nine for 135,000 hectares, for example.

Uzquiano complains about the neglect. The central government does not attend to the deteriorated camps, does not protect the personnel with life insurance, and does not support the processes they face against encroachers. “We do not receive support, but rather we are questioned, unauthorized, and unprotected.”

The Process

The case began on March 30, 2023, when park ranger Raúl Santa Cruz learned of the intentions to bring heavy machinery into the Virgen de Rosario sector without authorization. That same night, miner Ramiro Cuevas arrived to enter the protected area with heavy machinery, but the request was denied; it was then that Santa Cruz was threatened with derogatory words and even threatened with a chair.

Santa Cruz reported what happened to Uzquiano, who spread the incident on his social networks, which was seized upon by Cuevas to sue them for defamation. “They want to intimidate park rangers and environmental defenders so that they do not dare to denounce,” laments Uzquiano.

“We were never formally notified at our homes or workplaces,” denounces Uzquiano.

The machinery managed to enter the park under pressure and threats in the early hours of the following day. They are still operating in the protected area.

“We are very concerned that the Bolivian justice system, the Apolo court, admitted a lawsuit against two park rangers so diligently. All we wanted was to safeguard physical integrity and, on the other hand, prevent the entry of machinery into the protected area so as not to cause further deterioration and environmental pollution,” says Uzquiano.

From the National College of Biologists, they demand, through a statement, justice for the park rangers to enable solutions from the political administrative environment of the country, to guarantee their human and labor rights.

Uzquiano says that an adverse judgment will make them “not dare to confront a miner or logger because there will be no necessary support.”

There are around 295 park rangers distributed in all national parks in Bolivia, which in total cover an area of 182,716.99 square kilometers.

Guardaparques deben encarar acoso de avasalladores y de mineros ilegales

El guardaparques Marcos Uzquiano patrulla un área protegida. | Gentileza guardaparques

El guardaparques Marcos Uzquiano patrulla un área protegida. | Gentileza guardaparques Un guardaparques notifica sobre construcciones ilegales en el Tunari.

Un guardaparques notifica sobre construcciones ilegales en el Tunari.

Los guardaparques deben encarar la falta de recursos humanos, condiciones adversas de trabajo, asedio de avasalladores y acoso judicial en sus tareas de protección de los 23 parques y áreas protegidas en Bolivia. Se sienten indefensos y desautorizados.

El vicepresidente de la Asociación Boliviana de Guardaparques Agentes de Conservación (Abolac), Jimmy Torrez Muñoz, alerta que en el Parque Nacional Madidi el problema más serio es la presencia de la minería ilegal en los ríos.

Los guardaparques Marcos Uzquiano, quien actualmente ocupa el cargo de presidente de Abolac, y Raúl Santa Cruz son un ejemplo del acoso que existe por parte de las mineras que se dedican a la explotación ilegal en los parques del oriente boliviano; ambos afrontan un juicio por denunciar las agresiones de un empresario cuando internaba maquinaria pesada dentro del Parque Nacional Madidi “por la fuerza y sin ninguna autorización”.

El problema es más serio porque además no cuentan con el respaldo necesario de los administradores del Servicio Nacional de Áreas Protegidas (Sernap), que prefirió hacerse a un lado del litigio, pese a que el conflicto se desató en el cumplimiento de su trabajo. “Ni siquiera hemos recibido una llamada de respaldo”, lamenta Uzquiano.

Sobre el tema, el director ejecutivo del Sernap, Johnson Jiménez, aclaró que se trata de un proceso privado. Por lo tanto, no pueden involucrarse.

Torrez menciona que en otros parques como el del Área Protegida del Parque Nacional Toro Toro, en Potosí, el conflicto más serio es con los avasalladores de tierras.

Los guardaparques llevan adelante un proceso judicial por la toma de unas 2 hectáreas de la zona y, pese al mandamiento de “desapoderamiento y desalojo”, no se logra el retiro de los avasalladores. Más bien son víctimas de amedrentamiento y amenazas a través de votos resolutivos en los que piden su destitución. Desde el Sernap, en este caso, se apoyó al “cuerpo de protección” del Parque Nacional Toro Toro.

Torres menciona que en el Parque Nacional Tunari, donde actualmente trabaja, se suma la problemática de la explotación de los agregados y el amedrentamiento de los avasalladores que quieren apropiarse de tierra sobre la cota 2.750. “Muchas veces hemos sido secuestrados e incluso nos han amenazado con la quema de nuestros coches”, recuerda el guardaparques.

Todos los guardaparques deben encarar la violencia de grupos de avasalladores que quieren instalarse en las áreas protegidas, señala Torres.

Otro problema es que son muy pocos para atender miles de hectáreas. En el caso del Parque Nacional Tunari, son ocho para vigilar una extensión de 300 mil hectáreas, y, en el caso de la Reserva de la Biosfera y Estación Biológica del Beni, son nueve para 135 mil hectáreas, por ejemplo.

Uzquiano reclama por el abandono. Desde el Gobierno central no se atiende a los campamentos que se encuentran deteriorados, no se protege al personal con seguros de vida y no se apoya los procesos que encaran contra los avasalladores. “No recibimos el apoyo y más bien somos cuestionados, desautorizados y desprotegidos”.

El proceso

El caso se inició el 30 de marzo de 2023, cuando el guardaparque Raúl Santa Cruz se enteró de las intenciones de ingresar maquinaria pesada al sector de Virgen de Rosario, sin autorización. Ya en la noche del mismo día llegó el minero Ramiro

Cuevas para ingresar con la maquinaria pesada al área protegida, pero se le negó el pedido; fue entonces que Santa Cruz fue víctima de amenazas con palabras despectivas e incluso fue amenazado con una silla.

Santa Cruz dio parte a Uzquiano de lo sucedido y éste difundió el hecho en sus redes sociales, esto fue aprovechado por Cuevas para denunciarlos por difamación. “Ellos quieren amedrentar a los guardaparques y defensores ambientales para que no se atrevan a denunciar”, lamenta.

“Nunca fuimos notificados formalmente en nuestros domicilios ni en nuestro lugar de trabajo”, denuncia Uzquiano.

Las maquinarias lograron ingresar al parque bajo presión y amenazas en la madrugada del día siguiente. Las mismas siguen operando en el espacio protegido.

“Nos preocupa de sobremanera que la justicia boliviana, el juzgado de Apolo admita de manera tan diligente una demanda en contra de dos guardaparques. Lo único que queríamos era precautelar la integridad física y, por el otro lado, impedir el ingreso de la maquinaria al área protegida para que no siga ocasionando mayor deterioro y contaminación ambiental”, señala Uzquiano.

Desde el Colegio Nacional de Biólogos demandan, a través de un pronunciamiento, justicia para los guardaparques que permitan soluciones desde el entorno político administrativo del país, que permitan garantizar sus derechos humanos y laborales.

Uzquiano dice que una sentencia adversa hará que “no se atrevan a ponerse al frente de un minero o maderero porque no habrá el apoyo necesario”.

En Bolivia hay unos 295 guardaparques distribuidos en todos los parques nacionales que, en total, cuentan con una extensión de 182.716, 99 kilómetros cuadrados.