Editorial, El Deber:

It is both paradoxical and tragic. Where large deposits of silver and tin were discovered and exploited, today poor families and decimated communities survive. Where natural gas was discovered and exported, fueling the powerful industries of Brazil and Argentina, there are still regions that have not overcome the most critical levels of access to health and education, for example, although there were mayors who paved streets without having proper sewage systems.

This strange synthesis of luck and misfortune has been defined as the famous “resource curse”, a phenomenon repeated in various parts of the world where oil, emeralds, gold, or all kinds of minerals were discovered; strangers arrived, among them adventurers, outlaws, and businessmen, who emptied the earth’s bowels and left.

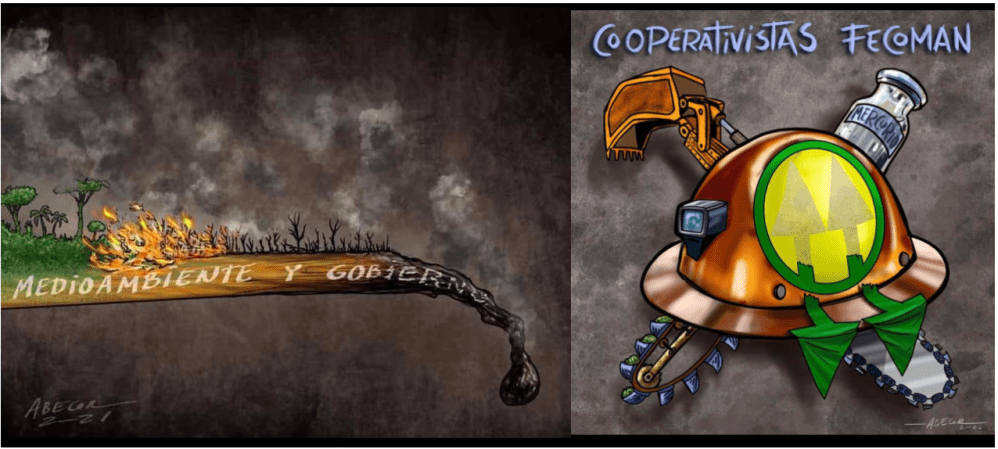

This story is repeated again in Bolivia with the gold rush, the precious mineral that is largely exploited by mining cooperatives and illegal companies that resist paying royalties and taxes and, most importantly, leave a trail of terrible environmental destruction and damage.

A clear example of this is the municipality of Teoponte, located in the north of La Paz. A documentary aired some years ago by Discovery Channel revealed that in the 1960s, over 500,000 ounces of gold were produced, and in return, the miners left their machinery rusted and useless. After a period of abandonment, Teoponte once again experienced the gold rush alongside Guanay, Mapiri, and Tipuani. Now the business is in the hands of mining cooperatives.

According to data from the National Institute of Statistics (INE), in 2022, exports of raw gold exceeded $3 billion, but due to pressures and dynamite blasts, gold mining cooperatives enjoy tax privileges and labor exemptions, use mercury indiscriminately, have access to subsidized diesel for machinery, and enjoy absolute impunity in all their actions.

In 2023, the cooperatives mobilized in La Paz to legalize their operations in nature sanctuaries, using dynamite, machinery, and a group of parliamentarians who are vigilant in stopping laws that affect their interests. Amid this conflict, David R. Boyd, United Nations Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment, reminded that: “Mining should never be allowed in protected areas. This violates the human right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment and, in the case of Bolivia, also violates the rights of Mother Nature. Outside protected areas, mines require the free, prior, and informed consent of indigenous peoples.” The pressure ceased, but the threat continues.

A clear example of this is the Tuichi River, where dozens of “legal” and illegal cooperatives settled. Several studies and journalistic reports estimate that only for road construction, approximately 378,000 square meters were deforested, equivalent to 54 stadiums. This situation affects the Tuichi and eleven other tributaries, has disrupted the lives of indigenous communities, and is causing high levels of contamination. And so, environmentalists and indigenous people denounce that at least 10 protected areas are under threat due to the greed of gold seekers.

Who has the word and authority to stop these disasters? The State, through the Ministries of Mining and Environment, along with other government agencies. But it is difficult to have hope and faith in that management. The reason is simple. The Government has strong political ties with the cooperatives, and now a representative of the sector is Minister of Mining. There are plenty of reasons for dismay because in the rivers affected by mining, not everything that glitters is gold, far from it.

Es paradójico y trágico a la vez. Allí donde se descubrieron y explotaron grandes reservorios de plata y estaño hoy sobreviven familias pobres y comunidades diezmadas. Allí donde se descubrió y exportó el gas natural que movió las potentes industrias de Brasil y Argentina hoy quedan regiones que aún no han superado los niveles más críticos de acceso a la salud y educación, por ejemplo, aunque no faltaron los alcaldes que asfaltaron calles sin tener un buen alcantarillado.

Esa extraña síntesis de suerte y desgracia se ha definido como la famosa maldición de los recursos naturales, un fenómeno repetido en varios lugares del mundo donde se descubrió petróleo, esmeraldas, oro o todo tipo de minerales; llegaron extraños. entre aventureros forajidos y empresarios, vaciaron las entrañas de la tierra y se marcharon.

Esa historia se repite nuevamente en Bolivia con la fiebre del oro, el precioso mineral que en gran medida es explotado por cooperativas mineras y empresas ilegales que se resisten a pagar regalías e impuestos y, lo más grave, dejan un rastro de terrible de depredación y daños al medio ambiente.

Un claro ejemplo de ello es el municipio de Teoponte, ubicado en el norte de La Paz. Un documental difundido hace algunos años por Discovery Channel reveló que en la década de los 60 del siglo XX se produjo más de 500.000 onzas de oro y, por todo pago, los mineros dejaron su maquinaria oxidada e inservible. Después de un tiempo de abandono, Teoponte volvió a vivir el auge del oro junto a Guanay, Mapiri y Tipuani. Ahora el negocio está en manos de las cooperativas mineras.

Según datos del Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (INE), en 2022, las exportaciones de oro en bruto superaron los 3.000 millones de dólares, pero a fuerza de presiones y dinamitazos las cooperativas mineras auríferas gozan de privilegios impositivos y exenciones laborales utilizan mercurio de forma indiscriminada, acceden al diésel subvencionado para mover y maquinaria y gozan de impunidad absoluta en todas sus acciones.

En 2023 los cooperativistas se movilizaron en La Paz para legalizar sus operaciones en santuarios de la naturaleza y para ello utilizaron dinamitas, maquinarias y un grupo de parlamentarios que están vigilantes para frenar normas que afecten sus intereses. En medio de ese conflicto, David R. Boyd, relator especial de las Naciones Unidas sobre derechos humanos y medioambiente, recordó que: “Nunca debe permitirse la minería en zonas protegidas. Esto viola el derecho humano a un medioambiente limpio, sano y sostenible y, en el caso de Bolivia, también viola los derechos de la madre naturaleza. Fuera de las áreas protegidas, las minas requieren el consentimiento libre, previo e informado de los pueblos indígenas”. La presión cesó, pero la amenaza continua.

Un claro ejemplo de ello es el rio Tuichi en el que se asentaron decenas de cooperativas “legales” e ilegales. Varios estudios y denuncias periodísticas estiman que solamente para la apertura de caminos se deforestó, aproximadamente, 378 mil metros cuadrados, equivalentes a 54 estadios. Situación que afecta al Tuichi y otros once afluentes, ha trastocado la vida las comunidades indígenas y está dejando un alto índice de contaminación. Y así. ambientalistas e indígenas denuncian que al menos 10 áreas protegidas están bajo amenaza por la angurria de los buscadores de oro.

¿Quién tiene la palabra y autoridad suficiente para frenar estos desastres? El Estado, a través de los ministerios de Minería y Medio Ambiente, junto a otras agencias gubernamentales. Pero es difícil tener esperanza y fe en esa gestión. La razón es simple. El Gobierno tiene fuertes lazos políticos con las cooperativas y ahora un representante del sector es ministro de Minería. Sobran razones para la desazón porque en los ríos afectados por la minería, no todo lo que brilla es oro, ni mucho menos.

https://eldeber.com.bo/opinion/oro-mercurio-y-deforestacion_359733