Editorial, El Deber:

For almost a decade, the Bolivian economy has had a worrying fiscal deficit, mostly attributed to the subsidy of imported hydrocarbons. It is undeniable that the subsidized price of gasoline and diesel has contributed to containing inflation and has generated economic benefits, which means that any attempt to eliminate it faces social resistance, as occurred in 2010 when President Evo Morales reversed his ‘gasolinazo’ ‘ because of popular pressure.

The deficit persists and is reflected in the 2024 General State Budget, which provides for a subsidy of 1.4 billion dollars for the acquisition of hydrocarbons and a fiscal deficit of 7.8%. Both figures indicate the continuity of the Government’s economic policy to avoid social conflicts. The crucial question is: How long will the State be able to bear these losses?

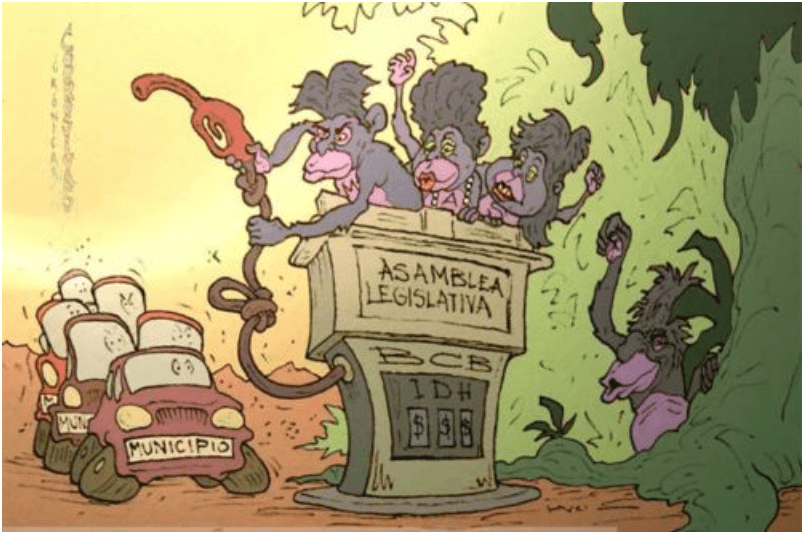

Like test balloons, voices have emerged within the ruling party that suggest the unsustainability of the status quo. Even President Luis Arce admitted in a speech that the country pays a “huge” price for the import of diesel and gasoline. A MAS deputy proposed reconsidering the subsidy, pointing out its links to illegal activities.

Experts warn about the negative effects of the subsidy, from state debt to the shortage of dollars and the low country risk rating. Smugglers take advantage of the situation, re-exporting up to 20% of the cheap fuel to other countries, where they sell it at the international price. Illegal mining also benefits, causing fuel shortages for domestic and legal consumption. The biggest losers are industry, construction and agriculture, sectors that pay taxes and generate growth for the country.

There are partial low-risk solutions that have not been taken advantage of. The Government has not taken steps to allow other actors to close the subsidy gap without significant social impact. For example, the law allows private entrepreneurs to directly import fuels, an option that would reduce tax expenditure and eliminate shortages for the productive sector. However, this possibility has not been accepted by centralism, apparently due to its desire to monopolize strategic decisions.

Some energy analysts propose sophisticated options, such as differentiated pricing for fuel consumers, suggesting that owners of high-end vehicles should pay more. They even propose that the supply of diesel and gasoline be denied to undocumented or ‘chutos’ vehicles.

Gradual adjustments and smart measures could minimize the impact on the population, allowing for a smoother transition rather than an abrupt removal of subsidies. A commitment to ethanol could reduce dependence on imported fuels, making it essential for the Government to negotiate with producers a greater supply of this substitute biofuel.

The participation of various actors, including civil society representatives and energy experts, in a process of consultation and dialogue is essential before making significant decisions. This would help to better understand the implications and consider various perspectives.

The need for adjustments becomes increasingly urgent, and there are now more politicians from the ruling party and the opposition who recognize it, except those who will surely try to take political advantage of an imminent popular rejection. Despite everything, the country has no choice but to advance in the gradual application of corrective measures to begin to reverse this unsustainable situation.

La economía boliviana arrastra desde hace casi una década un preocupante déficit fiscal, mayormente atribuido a la subvención de los hidrocarburos importados. Es innegable que el precio subvencionado de la gasolina y el diésel ha contribuido a contener la inflación y ha generado beneficios económicos, lo cual hace que cualquier intento de eliminarlo enfrente una resistencia social, como ocurrió en 2010 cuando el presidente Evo Morales revirtió su ‘gasolinazo’ por la presión popular.

El déficit persiste y se refleja en el Presupuesto General del Estado de 2024, que prevé una subvención de 1.400 millones de dólares para la adquisición de hidrocarburos y un déficit fiscal del 7,8%. Ambas cifras indican la continuidad de la política económica del Gobierno para evitar conflictos sociales. La pregunta crucial es: ¿Hasta cuándo podrá el Estado soportar estas pérdidas?

Como globos de ensayo, han surgido voces dentro del oficialismo que sugieren la insostenibilidad del statu quo. Incluso el presidente Luis Arce admitió en un discurso que el país paga un precio “descomunal” por la importación de diésel y gasolina. Un diputado del MAS propuso reconsiderar la subvención, señalando sus vínculos con actividades ilegales.

Los expertos alertan sobre los efectos negativos del subsidio, desde el endeudamiento estatal hasta la escasez de dólares y la baja calificación de riesgo-país. Los contrabandistas aprovechan la situación, reexportando hasta un 20% del combustible barato a otros países, donde lo venden al precio internacional. La minería ilegal también se beneficia, causando escasez de combustibles para el consumo interno y legal. Los grandes perjudicados son la industria, la construcción y la agropecuaria, sectores que tributan y generan crecimiento para el país.

Hay soluciones parciales de bajo riesgo que no se han sabido aprovechar. El Gobierno no ha tomado medidas para permitir que otros actores cierren la brecha del subsidio sin un impacto social significativo. Por ejemplo, la ley permite a los empresarios privados importar directamente combustibles, opción que reduciría la erogación fiscal y eliminaría la escasez para el sector productivo. Sin embargo, esta posibilidad no ha sido aceptada por el centralismo, aparentemente debido a su deseo de monopolizar las decisiones estratégicas.

Algunos analistas energéticos proponen opciones sofisticadas, como precios diferenciados para los consumidores de combustibles, sugiriendo que los propietarios de vehículos de alta gama deberían pagar más. Proponen, incluso, que se niegue el abastecimiento de diésel y gasolina a los vehículos indocumentados o ‘chutos’.

Ajustes graduales y medidas inteligentes podrían minimizar el impacto en la población, permitiendo una transición más suave en lugar de una eliminación abrupta de las subvenciones. Una apuesta por el etanol podría reducir la dependencia de combustibles importados, siendo esencial que el Gobierno negocie con los productores una mayor provisión de este biocombustible sustituto.

La participación de diversos actores, incluidos representantes de la sociedad civil y expertos en energía, en un proceso de consulta y diálogo, es fundamental antes de tomar decisiones significativas. Esto ayudaría a comprender mejor las implicaciones y considerar diversas perspectivas.

La necesidad de ajustes se vuelve cada vez más urgente, y ya hay más políticos del oficialismo y de la oposición que lo reconocen, excepto aquellos que seguramente tratarán de sacar rédito político de un inminente rechazo popular. A pesar de todo, el país no tiene más opción que avanzar en la aplicación gradual de medidas correctivas para comenzar a revertir esta situación insostenible.

https://eldeber.com.bo/edicion-impresa/una-subvencion-dificil-de-sostener_349053