By El Diario:

Government seeks to retain power

Analysts: Bolivia is experiencing an economic, energy, and education crisis

- Bolivia’s economy has not changed its productive model; it still depends on the sale of natural resources.

- Traditional sectors account for more than 70% of exports: mining and hydrocarbons.

The current administration of the Movement for Socialism (MAS) has led Bolivia into an economic, energy, and education crisis. Now, the government’s concern is focused on retaining power rather than solving the disaster caused by its improvised economic policies, without considering that the main problem lies in its excessive public spending, which feeds loss-making state-owned companies, according to analysts.

This perception also appears to be shared by Moody’s, which recently downgraded Bolivia’s credit rating again, noting a weak government with a risk of default.

“The economy is falling apart, Moody’s downgraded our rating to Ca, international liquid reserves are around 50 million dollars, and inflation is soaring at 14.6%. But the government continues to deny the crisis. It wouldn’t be surprising if the next one arrested is the data—on charges of statistical sedition,” wrote economist Gonzalo Chávez on his account @GonzaloCHavezA.

Economists warned in 2014 that Bolivia’s economy had entered a period of slowdown, when that year’s indicator dropped compared to 2013. However, authorities insisted on continued spending to drive growth and reduced international reserves.

At the time, economist and professor at the Technical University of Oruro (UTO), Ernesto Bernal, pointed out that the economy began to decelerate from 2014 due to low oil and gas prices. He also suggested the government should change its economic model.

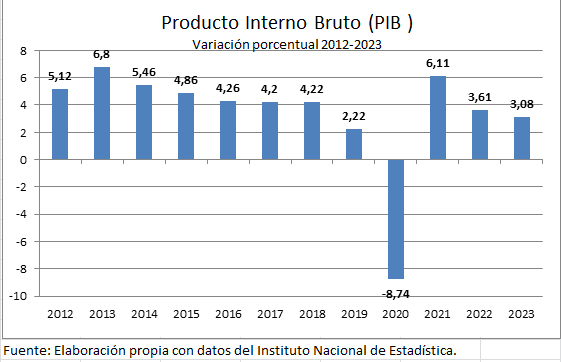

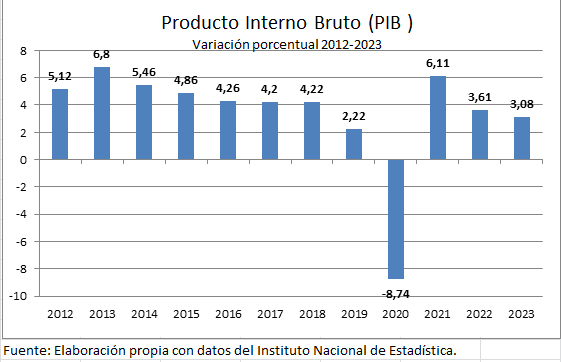

As a reminder, in 2013 the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew by 6.8%. In subsequent years, that figure steadily declined until it reached 2.2% in 2019. Then the pandemic in 2020 caused a -8.7% recession, and in 2021 a statistical rebound brought a 6.1% increase. But the pattern repeated: a year later, the government’s projections fell far short of reality.

International organizations and Bolivian economists independently agreed that growth in 2024 would not exceed 2%, and might be only slightly more—far below the government’s projection of 3.71%. For this year, 2025, the estimate has been lowered to 3.51%, while inflation is expected to rise to 7.5%.

The economic slowdown has been accompanied by a shortage of foreign currency, fuel scarcity, and inflation. The president of the Tarija Departmental College of Economists, Fernando Romero, said in an interview with this media outlet that the dollar shortage began when the Central Bank of Bolivia (BCB) announced it would buy U.S. currency from exporters at a rate higher than the official exchange rate.

This move triggered a currency shortage and the creation of a parallel market, as the BCB was unable to meet demand for dollars at the official rate. Desperate entrepreneurs and traders turned to the parallel market. The dollar is currently trading above 13 bolivianos.

Energy

The government’s dollar shortage and storms at the port of Iquique, Chile, caused last year’s fuel shortages—an issue that persists today. Service stations display “no gasoline” signs, and long lines of trucks wait to fill up on diesel for work.

This situation is due to declining gas and liquid production, stemming from the lack of exploration during Evo Morales’s administration—despite the then-Minister of Economy and Public Finance, Luis Arce, having the resources from the international oil price boom to invest in this area.

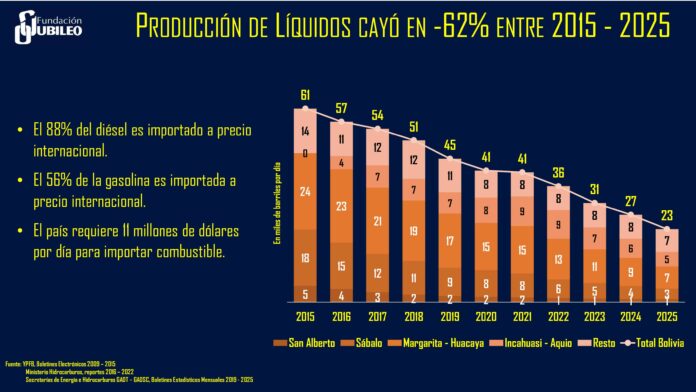

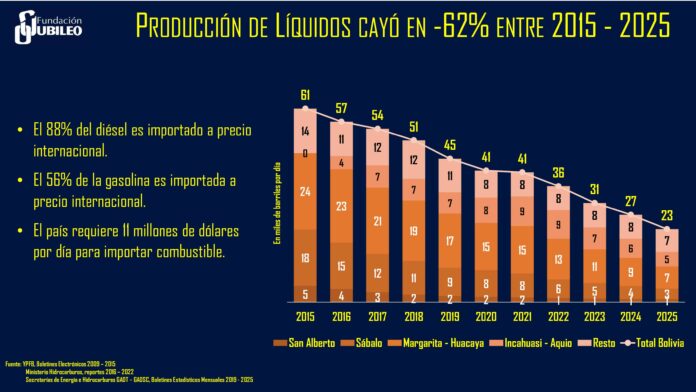

Production dropped from 60 million cubic meters per day (MMmcd) in 2014 to 32 MMmcd in 2024, and it is expected to fall further to 26 MMmcd this year, according to the Jubileo Foundation.

As a result, fuel imports and associated subsidies have increased annually. Budgets for subsidies have been exceeded and, in some cases, tripled, while import costs have also risen—approaching 4 billion dollars.

Bolivia needs, on average, 11 million dollars per day to import fuel—resources that are currently unavailable due to the shortage of foreign currency. This was warned by energy expert Raúl Velázquez from the Jubileo Foundation, according to a post by Fides Bolivia radio on its account @GrupoFides.

Chávez has also reiterated on social media that Bolivia has lost about 4 billion dollars in revenue. He explained that during the high oil price boom years, income reached 6 billion dollars, but in recent years that figure has barely exceeded 2 billion.

Economist and former BCB director Gabriel Espinoza asked on his account @g_espinoza: Why is the government increasing the ethanol percentage to levels likely incompatible with most of the country’s vehicle fleet?

“For a very simple reason: it’s not just that we don’t have dollars to import fuel (first bad news: on average, in 2023, we imported 55% of the gasoline we consumed—the highest figure in recent history), but also our production is plummeting (second bad news: for that reason, in the short and medium term, we’ll need even more dollars),” he reflects.

He argues that Bolivia’s economic situation is so dire that the appropriate comparison is not with Argentina (which produces much of what it consumes and now has a positive energy outlook), but with cases like Sri Lanka or Libya, which ran out of energy, food, and dollars in a short period—where prices rose rapidly and shortages began to appear in essential supply chains.

Education

Chávez not only points to an economic crisis, but also notes that the current administration has pushed education into crisis as well, as shown in a study conducted by the Plurinational Observatory for Educational Quality.

International media outlets such as Infobae headlined their concern over Bolivia’s education level: only three out of every 100 students passed math and chemistry in a diagnostic exam.

The study was carried out by the Plurinational Observatory for Educational Quality, and 40,000 students from public and private schools in both rural and urban areas participated in the test.

Moreover, in 2021, a study by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) concluded that education levels in Bolivia were low in subjects such as Mathematics, Reading, and Science, according to the Santa Cruz-based outlet El Deber.

As a reminder, the ruling party implemented the Avelino Siñani Law with the goal of improving the country’s educational quality. However, it appears that the law has failed to achieve its objectives.

Por El Diario:

Gobierno busca mantener el poder

Analistas: Bolivia registra crisis económica, energética y educativa

- La economía boliviana no cambió su matriz productiva, depende de la venta de recursos naturales.

- Los tradicionales tienen más del 70% de las exportaciones: minería e hidrocarburos.

La actual administración de gobierno del Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS) llevó a Bolivia a una crisis económica, energética y educativa, ahora la preocupación del Gobierno se centra en mantener el poder en vez de solucionar el desastre causado por sus políticas económicas improvisadas, sin tomar en cuenta que el problema principal se encuentra en su excesivo gasto público, alimentando a empresas deficitarias, de acuerdo con analistas.

Al parecer esa percepción también tiene la empresa Moody’s, cuando bajó nuevamente la calificación crediticia y observa un gobierno débil y con riesgo de un default.

“La economía se cae a pedazos, Moody’s nos rebaja la calificación a Ca, las reservas internacionales líquidas rondan los 50 millones de dólares y la inflación vuela al 14,6%. Pero el Gobierno sigue negando la crisis. No sería raro que el próximo detenido sea el dato. Por sedición estadística”, escribió el analista económico Gonzalo Chávez en su cuenta @GonzaloCHavezA.

Los economistas advirtieron en 2014, que la economía boliviana ingresó en un período de desaceleración, cuando este indicador bajó en comparación del 2013, pero las autoridades insistieron en seguir gastando para subir el crecimiento y redujeron las reservas internacionales.

En su momento, el economista y docente de la Universidad Técnica de Oruro (UTO), Ernesto Bernal, señaló que a partir de 2014 la economía ingresó en una desaceleración por los precios bajos del petróleo y el gas, además sugirió que el Gobierno debería cambiar su modelo.

Como se recordará en 2013, el Producto Interno Bruto (PIB) alcanzó un 6,8% de crecimiento, en los años posteriores la cifra fue cayendo hasta el punto de llegar a 2,2% en 2019; entretanto, la pandemia en 2020 provocó una recesión de -8,7%, en 2021 el rebote estadístico provocó una cifra positiva de 6,1%, pero la historia se volvió a repetir, pues un año después las proyecciones del Gobierno estuvieron lejos de la realidad.

Organismos internacionales y economistas bolivianos coincidieron, por separado, que el crecimiento de 2024 no pasaría de 2% o tal vez sea un poco más, que estará lejos de la proyección gubernamental de 3,71%.

Para la presente gestión 2025, se baja la estimación a 3,51%, mientras que la inflación sube a 7,5%.

A la desaceleración de la economía se sumó la escasez de divisas y la falta de combustible, así como la inflación. El presidente del Colegio Departamental de Economistas de Tarija, Fernando Romero, en una entrevista con este medio de comunicación, indicó que el problema con los dólares empezó cuando el Banco Central de Bolivia (BCB) anunció comprar la moneda estadounidense a los exportadores a un precio mayor a la cotización oficial.

Esa medida provocó la escasez de divisas y la creación del mercado paralelo, debido a que el BCB no podía con la demanda de dólares al tipo de cambio oficial, y la desesperación de empresarios y comerciantes se volcó al mercado paralelo. Actualmente, el valor está por encima de los 13 bolivianos.

Energética

La iliquidez de dólares que tiene el Gobierno y las marejadas en el puerto de Iquique, Chile, provocó el año pasado la escasez de combustibles, que se mantiene, en las estaciones de servicio con letreros de no hay gasolina, filas largas de camiones que aguardan cargar diésel para su trabajo.

Esa situación obedece a la caída de la producción de gas y líquidos, debido a la falta de exploración en la gestión de Evo Morales, cuando el ministro de Economía y Finanzas Públicas, Luis Arce, tenía en sus manos los recursos por el boom de los precios del petróleo en el mercado internacional para esta tarea.

De alcanzar una producción de 60 millones de metros cúbicos día (MMmcd) en 2014 a 32 MMmcd en 2024 y para la presente gestión se espera que la cifra siga bajando a 26 MMmcd, según los datos de la Fundación Jubileo.

En ese contexto, cada año las importaciones de combustibles aumentaron, así como los recursos del subsidio y el de importaciones. Los presupuestos programados para el subsidio pasaron y en algunos casos se triplicaron, mientras que para las compras la cifra también sube, bordea los 4.000 millones de dólares.

Bolivia necesita, en promedio, 11 millones de dólares al día para importar combustibles, recursos que actualmente no tiene disponibles debido a la escasez de divisas. Así lo advirtió el experto en temas energéticos de la Fundación Jubileo, Raúl Velázquez, de acuerdo a una publicación de radio Fides Bolivia en su cuenta @GrupoFides.

Ya Chávez reitera en sus redes sociales, que Bolivia dejó de percibir alrededor de 4.000 millones de dólares. Explicó que en los años del boom del precio alto del petróleo, los ingresos alcanzaron los 6.000 millones, pero en los últimos años la cifra apenas pasó los 2.000 millones.

El economista y exdirector del BCB, Gabriel Espinoza, publicó en su cuenta @g_espinoza, una pregunta: ¿Por qué el Gobierno sube el porcentaje de etanol a niveles que probablemente no sea tolerado por la mayoría del parque automotor en el país?

“Por una cuestión muy simple, no solo es que no tenemos dólares para importar combustibles (primera mala noticia: en promedio, en el 2023, importamos el 55% del consumo de gasolina, la cifra más alta de la historia reciente), sino que nuestra producción viene cayendo en picada (la segunda mala noticia: por ese motivo, en el corto y mediano plazo, necesitaremos cada vez más dólares)”, reflexiona.

Sostiene que la situación de la economía boliviana es tan dramática que la comparación correcta no es con Argentina (que produce mucho de lo que consumo y, ahora, tiene una perspectiva energética muy buena), sino con casos como los de Sri Lanka o Libia, que se quedaron sin energía, alimentos y dólares en un período muy corto, en el que los precios suben muy rápido y se empezaron a ver desabastecimientos en cadenas sensibles para la población.

Educación

Por otra parte, Chávez no sólo menciona que hay crisis económica, sino que la actual administración del Estado llevó a la educación a una crisis, así lo muestran el estudio que hizo el Observatorio Plurinacional de Calidad Educativa.

Medios internacionales, como Infobae, titularon que hay preocupación por el nivel educativo en Bolivia: solo tres de cada 100 estudiantes aprobaron matemáticas y química en un examen de diagnóstico.

Señala que el estudio fue realizado por el Observatorio Plurinacional de Calidad Educativa. 40.000 alumnos del área rural y urbana de colegios públicos y privados participaron en la prueba.

No obstante, en 2021 un estudio de la Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura (Unesco) estableció que los niveles de educación en Bolivia son bajos en áreas como Matemáticas, Lectura, Ciencias, publicaba el medio cruceño El Deber.

Como se recordará, el partido en función de gobierno puso en marcha la Ley Avelino Siñani, con el objetivo de mejorar la calidad educativa del país, y al parecer, la norma no cumplió los objetivos.