Francesco Zaratti:

I find significant ambiguities in the concept of “Economic Damage to the State” (EDS), which generally refers to the impact on the state’s assets by officials and authorities but has become a pretext for political persecution.

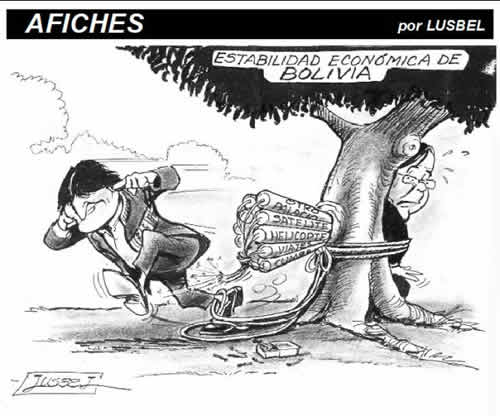

EDS is one of the most common offenses within a society that idolizes the State and tends to manifest itself on various scales. For example, it is not uncommon for public servants to take office supplies home, or for authorities to use official vehicles for personal errands, or for police officers to exchange fines for bribes, or for legislators who neither legislate nor oversee to increase their salaries at will, among other things. Some of these acts may seem trivial, but they reveal an ethical attitude towards the State that is inconsistent with the embraced ideology. It is often argued – as in the joke about the guy reprimanded by the public pool caretaker for urinating in the water – that “everyone does it.” “That’s true,” replied the caretaker, “but not from the diving board.”

Indeed, there are small and large economic crimes, as recognized by article 4.5 of Law 1390 of August 27, 2021, which sets at one million dollars (at the legendary exchange rate of 7 Bs/$) the “serious” harm to the State. So, what crimes are we talking about to classify them as serious?

Of course, there is the corruption of public servants to benefit (via insider information, fraud, or irregularities) from tenders and contracts, even to the detriment of the State’s interests, which is the one paying the bribes. Likewise, according to the MAS government, the recent MAS blockades caused immense damage to the State.

The performance of the State Attorney’s Office in international arbitrations is questionable, even within the framework of the “mission impossible” of defending arbitrary acts of governments. The Quiborax and Glencore cases, more recently, seriously challenge former lawyers of Evo, heads of that institution.

YPFB has officially admitted the loss of $130 million due to the exploratory failure of Boyuy. It was told from the beginning: since there was no specific contract, the drilling of Boyuy legally became part of the “services” of the Margarita field and, therefore, a recoverable cost for Repsol.

Certainly, there are acts that, even if they cause damage to the State, are not punishable, such as those resulting from the implementation of policies approved in a democratic election through government programs. It could be argued that Evo Morales’ “nationalization” is, in the long term, a failure because the final damage to the State outweighs the immediate benefits. However, it was a policy approved democratically, and that makes it immune. Hence the importance of debates between candidates, and not, cowardly, “with the people.”

The difference lies in how those policies are carried out. Let me explain. Lithium extraction is a national milestone, but was the choice of the evaporation method for the pools the result of rational analysis? We are talking about nearly a billion dollars literally “down the drain.” The same, and even more so, applies to the Ammonia and Urea Plant (PAU), which often produces more shutdowns than urea, even stopping only to allow more gas to be exported to Argentina. Did the defense in arbitrations not have insider information and incompetence that warrant an audit by the Comptroller? And didn’t Boyuy show more culpable desperation than legal care? In short, there is EDS also when state policies are implemented poorly, due to obvious personal responsibilities, and that damage should not go unpunished.

Finally, who will be held accountable for the damage caused by the cunning words of a Cuban agent and former US ambassador?

Encuentro grandes ambigüedades en el concepto de “Daño Económico al Estado” (DEE), que en términos generales es la afectación al patrimonio del Estado por parte de funcionarios y autoridades, pero que se ha vuelto motivo de persecución política.

El DEE es una de las faltas más comunes en el seno de una sociedad que idolatra al Estado y suele manifestarse a distintas escalas. Por ejemplo, no es raro que servidores públicos se lleven útiles de la oficina a su casa; o que autoridades utilicen vehículos oficiales para menesteres privados; o que policías canjeen multas por coimas; o que diputados, que no legislan ni fiscalizan, se incrementen el sueldo a su gusto, entre otras linduras. Algunos de esos hechos pueden parecer bagatelas, pero revelan una actitud ética hacia el Estado que no condice con la ideología abrazada. Se suele apelar -como en el chiste del tipo reprochado por el cuidador de la piscina pública por orinar en el agua- a que “todos lo hacen”. “Es cierto -replicó el cuidador- pero no desde el trampolín”.

En efecto, hay delitos económicos pequeños y grandes, como reconoce el art. 4.5 de la Ley 1390 de 27 de agosto de 2021 cuando fija en un millón de dólares (al cambio legendario de 7 Bs/$) la afectación “grave” al Estado. Pues, ¿de qué delitos estamos hablando para tipificarlos como graves?

Desde luego está la corrupción de servidores públicos para beneficiarse (vía infidencia, fraude o irregularidades) de licitaciones y contratos, incluso lesivos a los intereses del Estado que es quien paga las coimas. Asimismo, según el gobierno del MAS, los recientes bloqueos del MAS causaron un ingente daño al Estado.

La actuación de la Procuraduría del Estado en los arbitrajes internacionales es por demás cuestionable, aun en el marco de la “misión imposible” de defender actos arbitrarios de los gobiernos. Los casos Quiborax y Glencore, de más fresca memoria, interpelan seriamente a ex abogados de Evo, cabezas de esa institución.

YPFB ha admitido oficialmente la pérdida de 130 M$ por el fracaso exploratorio de Boyuy. Se les dijo desde un comienzo: al no tener un contrato específico, la perforación de Boyuy entró legalmente a ser parte de los “servicios” del campo Margarita y, por tanto, un costo recuperable de Repsol.

Por cierto, hay actos que, aun originando daños al Estado, no son punibles, como los que derivan de la aplicación de políticas aprobadas en una elección democrática mediante programas de gobierno. Se podría afirmar que la “nacionalización” de Evo Morales es, a largo plazo, un fiasco, porque el daño final al Estado supera los beneficios inmediatos. Sin embargo, fue una política aprobada democráticamente y eso la hace impune. De ahí surge la importancia de los debates entre candidatos, y no, cobardemente, “con el pueblo”.

La diferencia la marca la forma de llevar a cabo esas políticas. Me explico. La extracción del litio es un hito nacional, pero ¿la elección del método de evaporación de las piscinas fue fruto de análisis racionales? Estamos hablando de casi mil M$ literalmente “al agua”. Lo propio, y a mayor razón, vale para la Planta de Amoníaco y Urea (PAU) que suele producir más paros que urea, incluso llegando a parar sólo para permitir exportar más gas a la Argentina. ¿Acaso la defensa ante arbitrajes no tuvo infidencias e incompetencias que ameritan una auditoria de la Contraloría? ¿Y Boyuy no mostró más desesperación culposa que cuidados legales? En suma, hay DEE también cuando se aplican mal las políticas de Estado, por evidentes responsabilidades personales, y ese daño no debería quedar impune.

Finalmente, ¿A quién se le cobrará el daño causado por unos dichos ladinos de un agente cubano y ex embajador de los EE. UU.?

https://fzarattiblog.wordpress.com/2024/02/17/dano-economico-al-estado/