By Jorge Manuel Soruco, Vision 360:

The Park Ranger Has 20 Years of Experience

Always fascinated by the Amazon, the park ranger from San Buenaventura is fighting for his job and credibility after being unjustifiably dismissed.

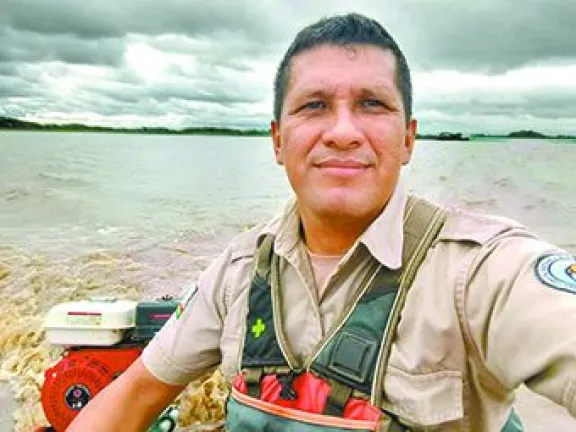

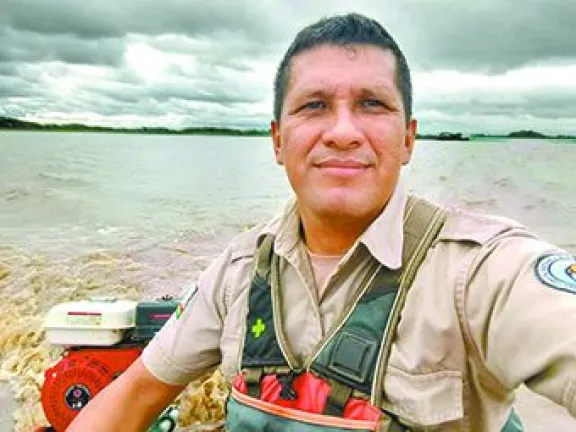

Marcos Uzquiano travels carrying two monkeys. PHOTO: Marcos Uzquiano

The jaguar is his spirit animal. Many significant moments in his life have been marked by encounters with the predator or events related to it. Marcos Uzquiano exhibits the jaguar’s fierceness when it comes to defending national biodiversity, whether against illegal mining or poaching.

His first encounter left a lasting impression on the native of San Buenaventura, in the northern part of La Paz department. “As a child, my brother and I went fishing. We were on the shore when we saw a jaguar jump across the stream, almost right next to us, and begin approaching. We were scared and started running, with the animal chasing us. Later, we thought it might not have intended to attack us because, if it had wanted to, it could have easily done so. We ran shouting toward a camp, which made the caretaker come out and shoot at the animal. That touched my soul and inspired me to find ways to protect life in that area,” he recalls.

It was the death of other specimens of that species that led Uzquiano to his current situation: unjustified dismissal and disciplinary proceedings by the management of the National Service of Protected Areas (Sernap).

The park ranger is the first firefighter. He is the one who must deal with poachers

A Struggle Fraught with Risks

“Sernap initiated disciplinary proceedings against me for denouncing forest fires and the death of a jaguar on my social media,” Uzquiano explains to Visión 360.

The animal was reportedly run over. It was later taken to the facilities of a Chinese company in Cochabamba, Sinohydro, where it was dismembered and butchered.

Adding to this is the park ranger’s participation in international events. At one such event held in Brazil last year, Uzquiano learned about a group of poachers entering the country from Argentina to kill jaguars.

After a period of investigation, Uzquiano and others, including environmental activists, filed a complaint with the Santa Cruz Prosecutor’s Office for the crime of biocide following the deaths of five felines in that department.

“They enter with irregular flights, which could even be linked to other illegal activities such as drug trafficking”; there are even reports of the involvement of a family from a former president, with ties to the authorities. He prefers to keep that identity confidential until the corresponding investigation is conducted.

It was only a few months later, on December 31, that Uzquiano received the dismissal memorandum, but without any explanation. Last week, a disciplinary process was initiated against him because, as he was informed, he violated rules by participating in international events and being part of the Bolivian Association of Park Rangers and Conservation Agents (Abolac).

These actions sparked public rejection, as Marcos is known as an important worker defending national parks. Protests in his favor took place at the Sernap offices.

They enter with irregular flights, which could even be linked to other illegal activities such as drug trafficking.

However, its director, Johnson Jiménez Cobo, did not respond to the criticisms. He even went as far as to accuse journalists of “harassing” him when they asked about the reasons for Uzquiano’s dismissal and those of other officials.

But this is not the first time Marcos has faced dismissal and legal proceedings. He already went through this in 2015 and 2019, always after denouncing an illegal act.

Like his colleagues in various national parks, Uzquiano has faced pressure and even threats from different groups seeking to take advantage of the reserves.

Initially, these came from illegal mining entrepreneurs. “It’s an activity that holds a lot of economic power, the ability to interfere or generate influence in political decisions, even at the national level,” he explains.

“We’ve suffered a lot of persecution, a lot of threats, not just professionally but also physically. Many park rangers have been intimidated, prevented from carrying out their duties. We were threatened with having our motorcycles taken away, being beaten, or thrown into the river. Even with being disappeared during the patrols we conduct,” adds the park ranger.

But that doesn’t stop him. Whether in Madidi, Pilón Lajas, Tipnis, or Beni, Uzquiano continued traveling long distances to try to prevent the loss of the ecosystem he has been protecting for over 20 years.

A life in the jungle

His interest in the work of a park ranger began in his childhood. “Growing up next to the river and the beauty of our country, in addition to the threats it faces. I felt it so personal that when I saw people in the 1980s coming in to exploit it, it bothered me. From a very young age, I would tell my mom that I wanted to become a tiger, a jaguar.”

In 1995, the Madidi National Park was created. Taking advantage of that, the teenager Marcos volunteered as a park ranger. That’s how he began learning the secrets of this profession.

We have suffered a lot of persecution, a lot of threats, not just professionally but also physically.

At the same time, he pursued a degree in Accounting. He also completed specializations in conservation and management of protected areas, which always brought him back to Madidi. “As a volunteer, I did tasks such as managing the radios, receiving reports from the park rangers, and acting as a night watchman at the main camp. I cleaned, took care of things, and slept there. And I loved it.”

In 2001, he applied for a merit-based position and successfully obtained the role of park ranger at Madidi National Park. “It was the greatest achievement of my life. I felt immense pride, an intense feeling, of having accomplished something I truly wanted to do since I was a child.”

He worked in that area for eight years. After a four-year break, he returned, this time as the protection chief for Zone B of Madidi Park in the Apolo area. In 2015, he was transferred to the Isiboro Sécure Indigenous Territory and National Park (Tipnis). In 2020, during the pandemic, he worked at the Pilón-Lajas Biosphere Reserve and TCO, and in 2021, he was transferred to the Beni Biosphere Reserve and Biological Station.

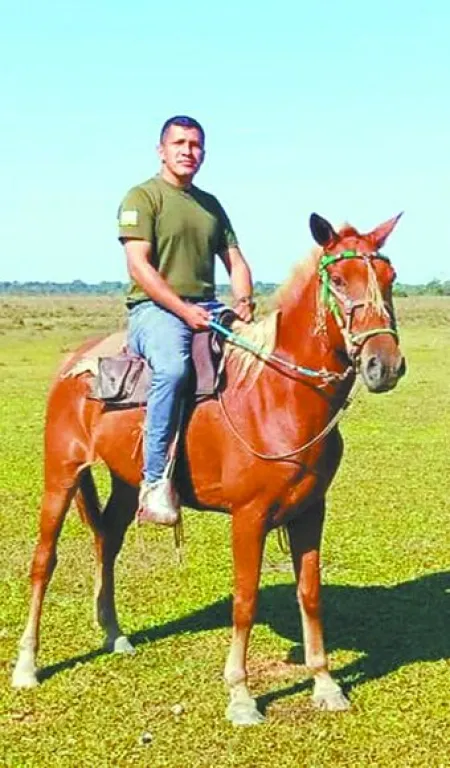

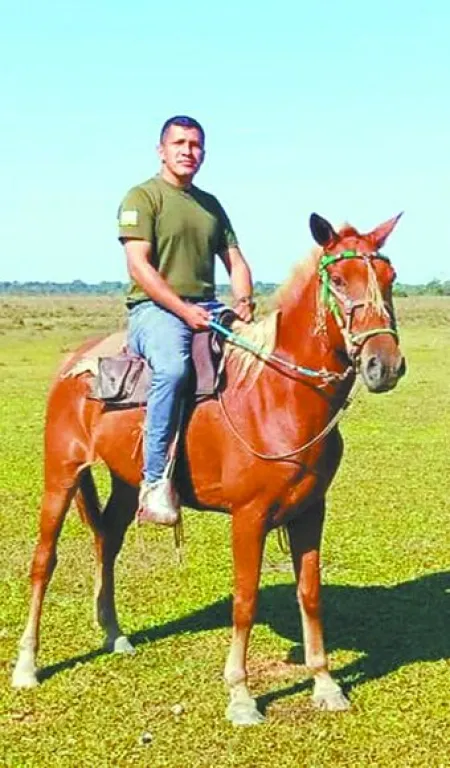

During these 20 years, he traversed vast jungle and high-altitude areas by motorcycle, jeep, boat, horseback, and on foot. He realized that his role, and that of his 305 colleagues across the country, is to be the first line of defense for the ecosystem. “The park ranger is the first firefighter, the one who has to negotiate with poachers so they don’t kill species. Keep in mind that we are far from help, and any assistance takes days to arrive.”

Not everything is bad. In fact, the rewards outweigh the disappointments, such as helping biologists identify a new species, saving sloths, collaborating with indigenous communities, and perhaps the most spectacular, encountering his spirit animal again.

“I was sleeping in a camp, alone. I heard a very faint whistle in the early morning and realized it was the jaguar. It came to sniff behind my tent; I could feel it clearly, right next to my head. We don’t carry weapons, but we do have a flashlight and machete, so I gathered my courage and confronted it. It looked at me and turned around, as if recognizing me.”

BIOGRAPHY

DATE OF BIRTH

He was born in San Buenaventura, department of La Paz, on August 16, 1976.

STUDIES

He is an accounting assistant. He is a technical expert in tourism and also studied English, a language he speaks fluently. He is also a technical assistant in conservation and sustainable management of natural resources.

ANIMALS

He helped identify new species within Madidi National Park. He loves big cats, monkeys, and sloths. However, he is not very fond of large spiders.

Por Jorge Manuel Soruco, Visión 360:

El guardaparques tiene 20 años de experiencia

Siempre fascinado por la Amazonia, el guardaparques de San Buenaventura se encuentra luchando por su puesto de trabajo y credibilidad tras ser despedido sin justificación.

Marcos Uzquiano viaja cargando dos monos. FOTO: Marcos Uzquiano

El jaguar es su animal espiritual. Muchos puntos importantes de su vida estuvieron marcados por encuentros con el depredador o por hechos relacionados con él. Y es que Marcos Uzquiano muestra la fiereza del felino cuando se trata de defender la biodiversidad nacional, ya sea de la minería ilegal o de la caza furtiva.

Su primer encuentro dejó una marca permanente en el originario de San Buenaventura, del norte del departamento de La Paz. “De niño fuimos con mi hermano a pescar. Estábamos en la orilla cuando vimos a un jaguar saltar el arroyo, casi junto a nosotros, y comenzar a acercarse. Nos asustamos y comenzamos a correr, con el animal detrás de nosotros. Después pensamos que tal vez no tenía la intención de atacarnos, porque si quería lo hubiese logrado fácilmente. Nos acercamos gritando a un campamento, lo que hizo que el cuidador saliera y disparara contra el animal. Eso me tocó en el alma y me animó a ver maneras de proteger a la vida en esa zona”, recuerda.

Fue la muerte de otros ejemplares de esa especie lo que llevó a Uzquiano a su actual situación: el despido injustificado y proceso disciplinario por parte de la dirección del Servicio Nacional de Áreas Protegidas (Sernap).

El guaraparques es el primer bombero. Es quien tiene que lidiar con los cazadores furtivos

Una lucha con muchos riesgos

“El Sernap me inició un proceso administrativo sancionador por denunciar en mis redes sociales sobre los incendios forestales que estaban ocurriendo y la muerte de un jaguar. Ambos casos en mis redes sociales”, explica a Visión 360.

El animal supuestamente fue atropellado. Posteriormente se lo llevó a las instalaciones de una empresa china en Cochabamba, la Sinohydro, donde fue descuartizado y desmembrado.

A eso se suma la participación del guardaparques en eventos internacionales. En uno de ellos, realizado en Brasil el año pasado, Uzquiano se enteró de un grupo de cazadores furtivos que ingresaban al país desde Argentina para matar jaguares.

Así, tras un periodo de investigación, el guardaparques y otras personas, incluyendo activistas ambientalistas, denunciaron ante la Fiscalía de Santa Cruz el delito de biocidio por la muerte de cinco felinos en ese departamento.

“Ingresan con vuelos irregulares, que, incluso, pueden estar vinculados con otras actividades ilícitas como narcotráfico”; incluso hay denuncias de la participación de una familia de un expresidente, con vínculos con las autoridades. Esa identidad prefiere mantener en reserva hasta que se haga la investigación correspondiente.

Fue así que pocos meses después, el 31 de diciembre, Uzquiano recibió el memorándum de despido, pero sin ninguna explicación. La semana pasada se le inició un proceso disciplinario, porque, según le informaron, incumplió normas al participar en eventos internacionales y ser parte de la Asociación Boliviana de Guardaparques y Agentes de Conservación (Abolac).

Estas acciones provocaron el rechazo de la población, puesto que Marcos es conocido como un importante trabajador en defensa de los parques nacionales. Manifestaciones a su favor se dieron en las instalaciones del Sernap.

Ingresan con vuelos irregulares, que, incluso, pueden estar vinculados con otras actividades ilícitas como narcotráfico.

Sin embargo, su director, Johnson Jiménez Cobo, no respondió a las críticas. Incluso llegó a acusar a los periodistas de “acosarlo”, cuando le preguntaban por las razones del despido de Uzquiano y de otros funcionarios.

Pero, no es la primera vez que Marcos se enfrenta a una destitución y procesos. Ya lo hizo en 2015 y 2019, siempre después de denunciar un acto ilegal.

Al igual que sus compañeros en los distintos parques nacionales, Uzquiano ha recibido presión, e incluso amenazas, de diferentes grupos interesados en aprovecharse de las reservas.

Inicialmente fueron empresarios de la minería ilegal. “Es una actividad que tiene mucho poder económico, mucha capacidad de interferir o generar influencias en las disposiciones políticas, incluso a nivel nacional”, explica.

“Hemos sufrido mucha persecución, mucha amenaza, no solamente laboral sino también física. Muchos guardaparques han sido intimidados, impedidos de cumplir sus funciones. Se nos amenazó con quitarnos las motocicletas, de ser golpeados o tirados al río. Incluso de desaparecernos en los patrullajes que realizamos”, agrega el guardaparques.

Pero eso no lo detiene. Ya sea en el Madidi, Pilón Lajas, Tipnis o Beni, Uzquiano continuó recorriendo grandes distancias para tratar de evitar que se pierda el ecosistema que viene protegiendo desde hace más de 20 años.

Una vida en la selva

Su interés en el trabajo de guardaparques surgió en su niñez. “Creciendo al lado del río y la belleza de nuestro país, además de las amenazas que enfrenta. Lo sentía tan mío que cuando miraba a gente que, en la década de los 80, entraban a depredar, me molestaba. Desde muy niño le decía a mi mamá que quería convertirme en un tigre, en un jaguar”.

En 1995 se creó el Parque Nacional Madidi. Aprovechando eso, el adolescente Marcos se presentó como guardaparques voluntario. Así comenzó a aprender los secretos de esa profesión.

Hemos sufrido mucha persecución, mucha amenaza, no solamente laboral sino también física.

Paralelamente siguió la carrera de Contabilidad. También realizó especializaciones en conservación y manejo de áreas protegidas. Y siempre lo llevaba de vuelta al Madidi. “Como voluntario, hacía labores como de atención de las radios, recibir los reportes de los guardaparques, hacer de sereno en el campamento principal. Limpiaba, cuidaba, dormía ahí. Y me encantaba”.

En 2001 se postuló a un concurso de méritos y logró, así, obtener el cargo de guardaparques del Parque Nacional Madidi. “Para mí fue el logro más grande de mi vida. Sentí un orgullo tremendo, una sensación así, bien intensa, de haber logrado algo que yo realmente quería hacer desde niño”.

Trabajó ocho años en esa zona. Después de una pausa de cuatro años regresó, pero esta vez con el cargo de jefe de protección de la zona B del Parque Madidi, en la parte de Apolo. En 2015 fue trasladado al Territorio Indígena y Parque Nacional Isiboro Sécure (Tipnis). En el 2020, en la pandemia, trabajó en la Reserva de la Biosfera y TCO Pilón-Lajas y en 2021 fue transferido a la Reserva de la Biosfera y Estación Biológica de Beni.

Durante esos 20 años recorrió amplias zonas selváticas y de altura en moto, jeep, bote, caballo y a pie. Comprendió que su papel, y el de sus 305 colegas en todo el país, es el de ser la primera línea de defensa del ecosistema. “El guardaparques es el primer bombero, el que tiene que negociar con los cazadores furtivos para que no maten especies. Tenga en cuenta que estamos alejados y toda ayuda está a días de llegar”.

No todo es malo. De hecho, las satisfacciones son más que las decepciones, como ayudar a los biólogos a identificar una nueva especie, salvar a los perezosos; colaborar con las comunidades indígenas y, quizá lo más espectacular, volverse a topar con su animal espiritual.

“Estaba durmiendo en un campamento, solo. Escuché un silbido, muy fino, en la madrugada y me di cuenta que era el jaguar. Llegó a olfatear detrás de mi carpa, lo sentí clarito, aquí al lado de mi cabeza. No portamos armas, pero sí linterna y machete, por lo que me armé de valor, lo encaré de frente. Me vio y se dio la vuelta, como reconociéndome”.

BIOGRAFÍA

Í° NACIMIENTO · Nació en San Buenaventura, departamento de La Paz, el 16 de agosto de 1976.

Í° ESTUDIOS · Es auxiliar contable. Es técnico medio en turismo, también estudió inglés, idioma que maneja de forma fluida. Asimismo es técnico auxiliar en conservación y manejo sustentable de los recursos naturales.

Í° ANIMALES · Ayudó a identificar nuevas especies dentro del parque Madidi. Ama a los grandes felinos, monos y perezosos. Eso sí, no es muy amigo de las grandes arañas.

It is highly upsetting that this extermination came by the money Chinese bid. By corrupting the local people, illegal Chinese miners not only bring mercury, which contaminates Bolivian rivers, but also poisons the local indigenous people. The Chinese illegally profit from the gold they extract, and, due to their despicable preferences, they go in search of jaguar fangs.