By Marco Antonio Belmonte, Vision 360:

- Land seizures,

- export restrictions,

- legal uncertainty for investments, and

- infrastructure problems are hindering greater development.

Santa Cruz is a leader in productive development, exports, and is the fastest-growing economy in Bolivia. However, to further contribute to both its own development and that of the country, it faces four major obstacles: lack of legal certainty for investment, export restrictions, land seizures, and infrastructure and logistics problems.

“Land seizures, blockades, dollar shortages, irregular diesel supply, droughts that have severely affected soybean and winter crops, low international prices, and the uncertainty stemming from the country’s political situation—all of this complicates the environment for investment, production, and exports in the region,” Gary Rodríguez, general manager of the Bolivian Institute of Foreign Trade (Ibce), told Visión 360.

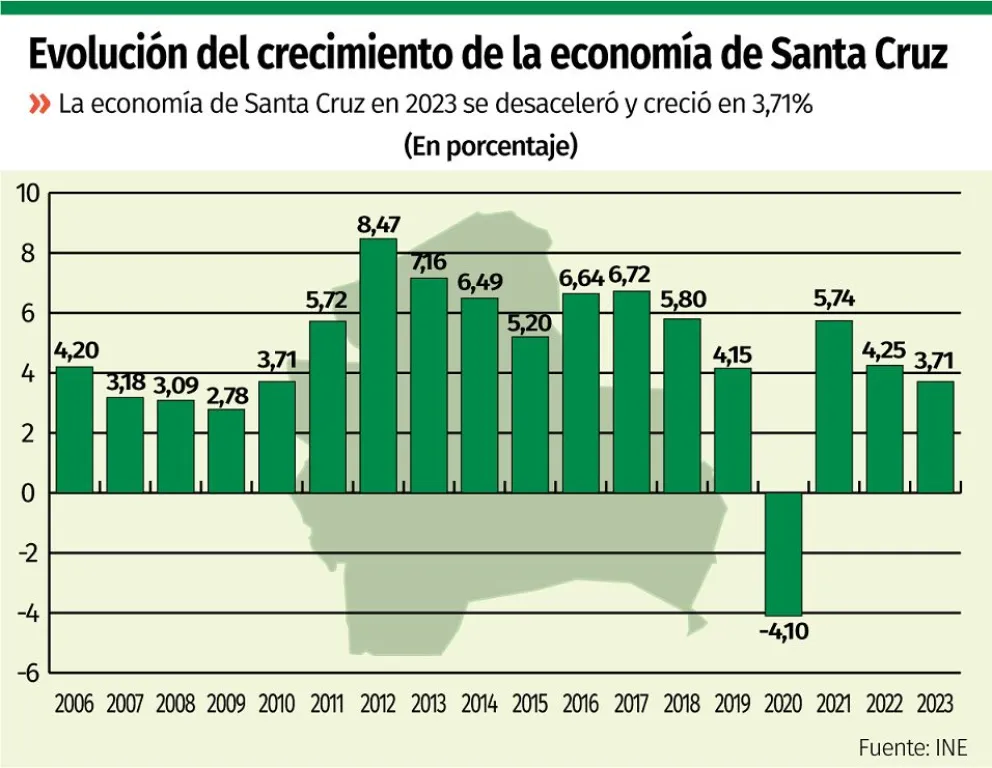

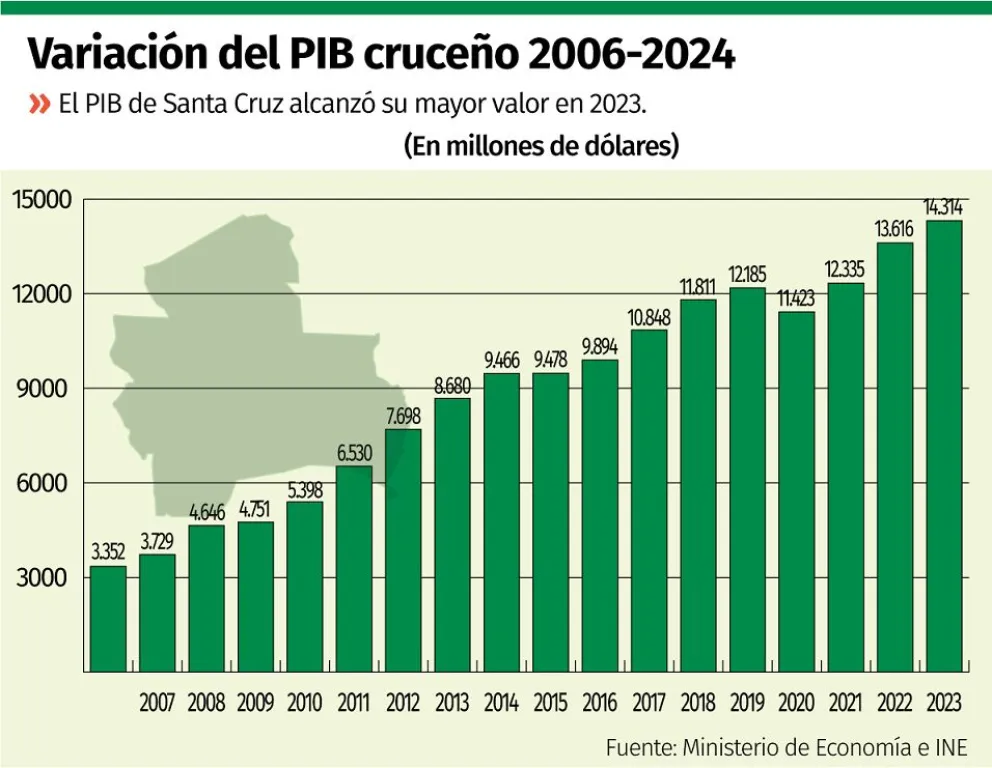

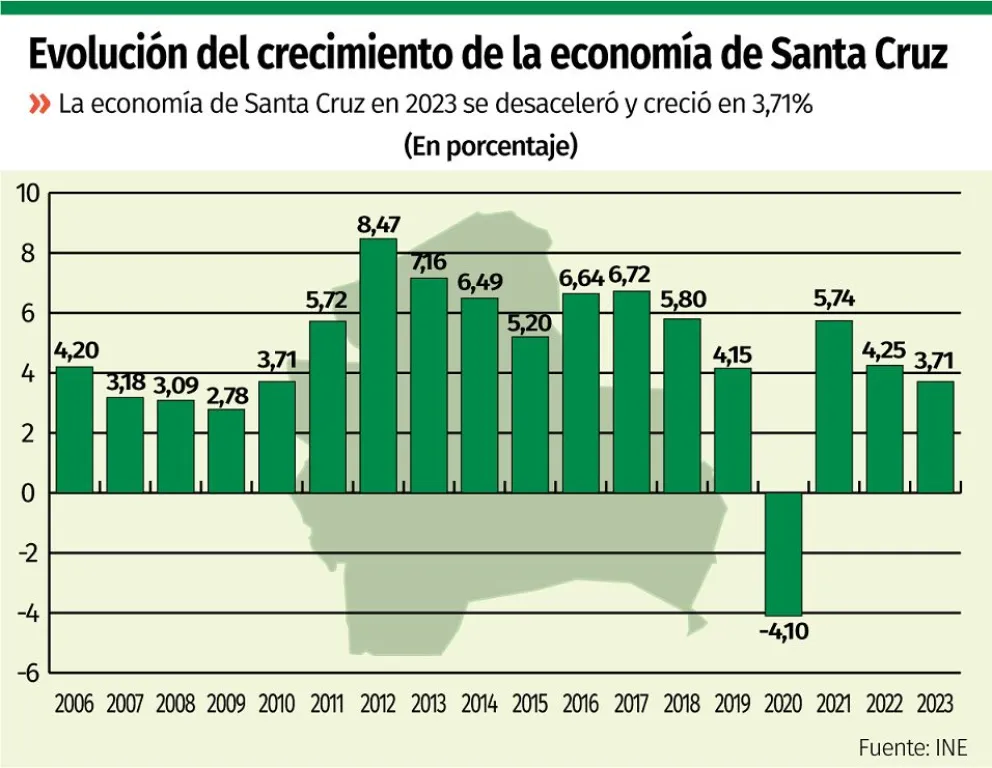

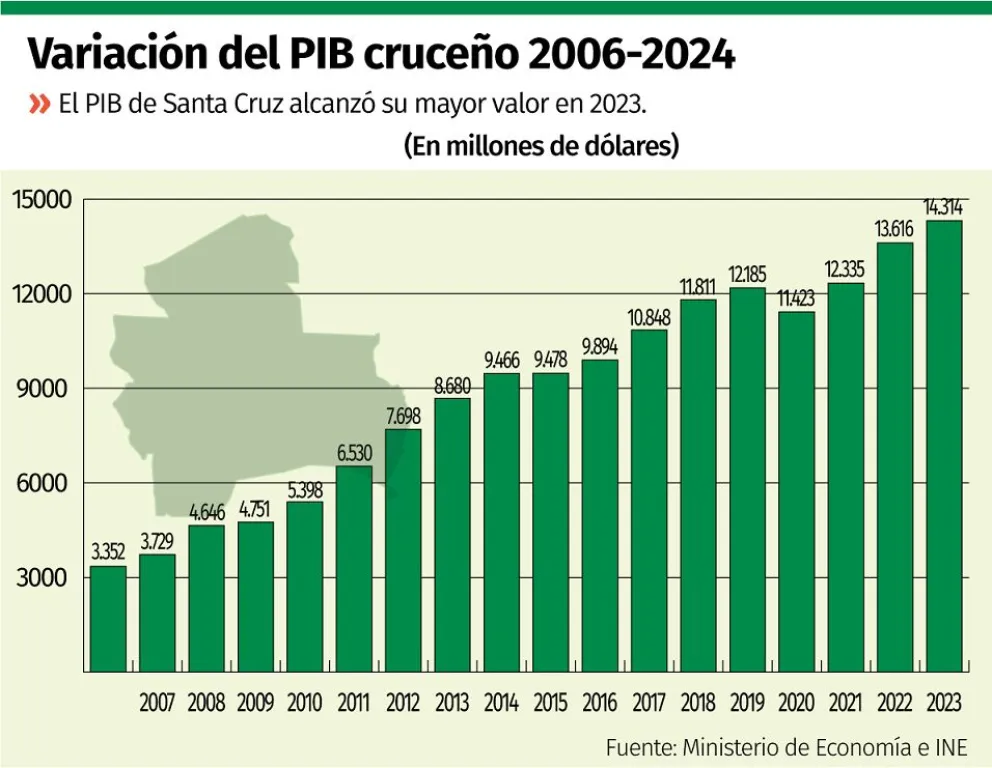

This September 24th, the department of Santa Cruz marks another anniversary of its fight for freedom. Last year, its GDP reached $14.314 billion, according to data from the National Institute of Statistics (INE), with an economic growth rate of 3.71%, lower than the 4.25% reported in 2022.

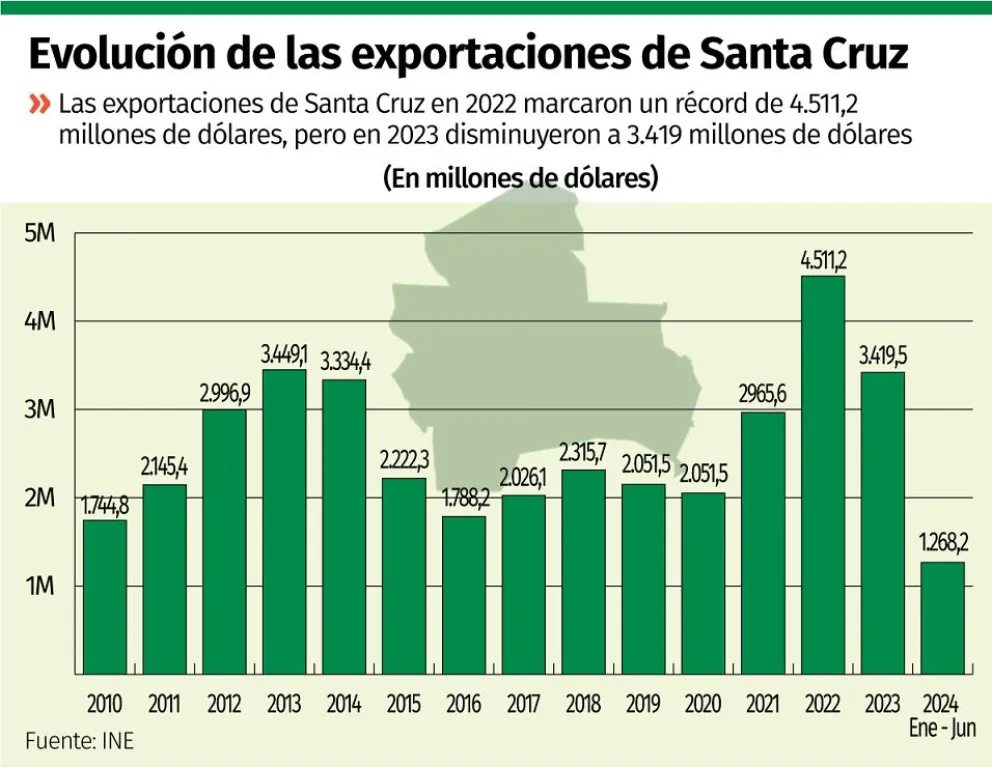

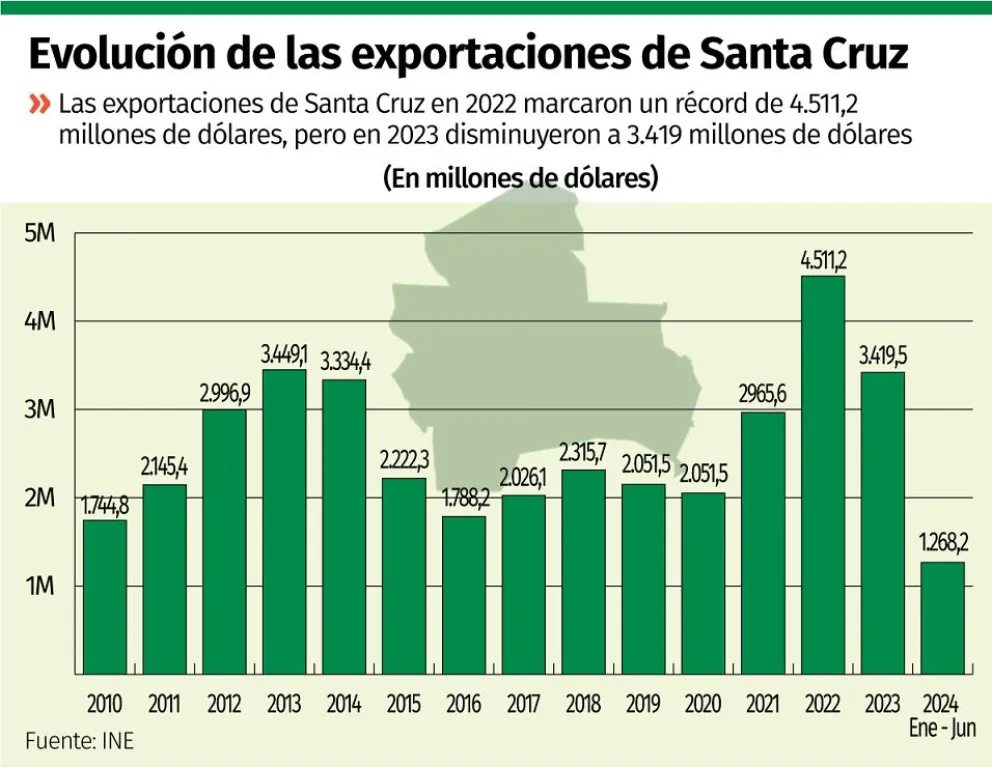

Last year, Santa Cruz’s exports reached $3.419 billion, and in the first half of this year, the department’s sales totaled $1.268 billion.

It is estimated that Santa Cruz contributes about 31% to 32% of Bolivia’s GDP and is now solidifying its position as the country’s economic engine, driven by sectors such as food production, natural gas, livestock, genetics, agribusiness, agriculture, exports, hospitality, services, and construction.

More Dynamism?

What is needed for Santa Cruz to multiply its economic dynamism? According to Gary Rodríguez, the agro-industrial and forestry sectors can provide immediate results, but legal certainty over land is crucial. This includes guarantees for investors who risk their capital, ensuring they can plan for returns on their investments.

Rodríguez also notes that Santa Cruz’s productive model could be the solution to Bolivia’s ongoing economic crisis, marked by declining Net International Reserves (RIN), lower foreign currency availability, reduced natural gas production and exports, and increased fuel imports.

“How can Santa Cruz contribute to the solution? The answer is through more dollars. But to get more dollars, I need to export more, import less, and attract foreign capital through increased Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). The problem is that nobody will give money for free—the country’s risk is high. To issue bonds, we would need to pay a 20% interest rate, and attracting investment in such a conflict-ridden environment is challenging—capital is leaving rather than coming in,” Rodríguez explains.

However, to export more, increased production is necessary, which in turn requires more investment and a stable environment guaranteed by the country.

“To achieve this, legal security, market security, and ensuring that economic agents—whether foreign, local, or domestic—are heard in their demands and needs to activate the department’s potential is crucial,” adds Rodríguez.

He emphasizes that 90% of the regional economy relies on private activity, grounded in the values of business freedom, competitiveness, cooperative association, and global integration. “This is what can help Bolivia move forward,” he underscores.

Land Invasions

Another obstacle is land grabs. It is not possible, says Rodríguez, that there are currently more than 100 properties taken, as occurred in 2013, but which later decreased to 10, thanks to agreements reached with the Government to resume institutionality. This is in view of the commitment to triple food production from 15 million to 45 million tons.

He stresses the need to stop land invasions because agricultural, livestock, and forestry activities are high-risk industries, vulnerable to climate conditions, price fluctuations, and other uncertainties.

Without export quotas

Additionally, it is considered necessary to provide investors with certainty that their efforts will translate into economic results because no one will invest to lose or overproduce if they cannot export.

“In this sense, existing restrictions must be eliminated, and there must be freedom of exportation. If production is not exported on time, there is a risk of prices dropping,” emphasizes Rodríguez.

Lack of infrastructure

Economist Gonzalo Chávez Barrancos believes that for Santa Cruz to grow further and increase its exports, the department must reduce logistical costs because it cannot sell more when it is expensive.

“For example, if a railway network could be developed that safely connects us to ports, logistical costs could be reduced by more than 50% for freight. What this means is that if a ton from Santa Cruz to Arica costs $150, and we could lower that cost by $70 per ton, imagine the savings that would exist; in that way, the money stays with the producer and not with the transporter and is reinvested in the economy,” he emphasized.

“We do not export more because costs are high, but that is because there is no necessary transport infrastructure; there is also no adequate gas and energy infrastructure to set up other industries. If we had high-tension energy in the Chiquitanía, the valleys, and gas, many industries could be taken to those places and generate greater development,” Chávez pointed out.

Along with this, the development of Puerto Busch is pending, but it requires a multimillion-dollar investment because the port must be built and infrastructure invested in; likewise, the HUB of Viru Viru, which was another project that would allow the generation of other value-added industries. However, the project is postponed.

Other niches

Chávez Barrancos argues that the economy of Santa Cruz is not only driven by the productive agro-industrial sector. It evolved from oil production, which was later complemented by agriculture and livestock.

“The reflection is that currently, it exports more than $300 million in livestock through one company (BFC), and the trend is that with other companies engaged in high genetics, in two to three years, it could export $1 billion,” he highlights.

Additionally, there are other sectors that, with the agreements in place with China, are taking advantage of the opportunity to produce and export more chia and sesame to that vast market, aiming to increase exports from $120 or $150 million to $500 million in three to four years.

In services, many companies have established themselves in the department; two banks and two major insurance companies have their base in the region. “The rest of the country consumes a large part of what Santa Cruz produces, and the circumstances force us to adopt technology and improve; in fact, the intensive livestock farming that existed 30 years ago no longer exists; now we have high-genetics livestock for export. Dairy companies have increased their quality and productivity,” he emphasizes.

Santa Cruz also has tourism, but not the receptive type characteristic of places like Uyuni; rather, the region generates more business and corporate tourism. “It’s more of a mid-range and high-end tourism, where tourists arrive, make business deals, and leave, similar to São Paulo. There is tourism in Chiquitanía and the valleys, but it is mostly domestic,” he notes.

For 2025, the GDP of Santa Cruz is estimated to reach Bs 47.588 billion

The GDP of Santa Cruz could reach 47.588 billion bolivianos ($6.937 billion) by 2025, according to estimates by Jorge Akamine, president of the National College of Economists of Bolivia.

Thus, the contribution of the economy of Santa Cruz to the national GDP, which was 33.9% in 2021, 34.1% in 2022, and 34.3% in 2023, will increase to 34.6% this year and to 35% in 2025, the year of the Bicentennial.

The GDP per capita has risen from $1,835 in 2009 to $4,105 in 2023.

The production volumes by crop groups for the 2021-2022 campaign show that 83.9% of the crops in Santa Cruz are industrial.

Following that, cereals represent 11.9%, fruit crops occupy 1.8%, vegetables 1.2%, and tubers and roots 1.2%. In 2022, Santa Cruz produced 156,204 tons of beef.

It leads in production, foreign trade, tax contributions, credit portfolio, productive employment, and consumption of cement and electricity, all linked to investments and productive activity, respectively. Over two decades, it has consolidated this national leadership. With an area representing 34% of the national territory and 24.5% of the Bolivian population, it is the region with the highest economic activity and generates nearly a third of the country’s GDP. The evolution of Santa Cruz’s economy is closely tied to the increase in investment, particularly productive private investment.

Por Belmonte, Vision 360:

- Avasallamientos de tierra,

- restricciones a las exportaciones,

- inseguridad jurídica a la inversión y

- problemas de infraestructura frenan un mayor desarrollo.

Santa Cruz es líder en desarrollo productivo, en exportaciones y es la economía que más crece; sin embargo, para contribuir más a su desarrollo y del país enfrenta cuatro obstáculos: falta de seguridad jurídica a la inversión, restricciones a las exportaciones, avasallamientos, y problemas de infraestructura y logística.

“Continúan los avasallamientos, los bloqueos, la escasez de dólares, no hay una normalidad en la provisión de diésel, la sequía ha hecho estragos en la soya y cultivos de invierno…, los precios a nivel internacional están bajos y la incertidumbre que deviene de la situación política del país, todo ello complica el entorno para la inversión, producción y exportación en la región”, asegura a Visión 360 Gary Rodríguez, gerente del Instituto Boliviano de Comercio Exterior (Ibce).

Este 24 de septiembre, el departamento de Santa Cruz cumple un aniversario más de su gesta libertaria. El año pasado, su PIB alcanzó un valor de 14.314 millones de dólares, según datos del Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE) y la economía creció en 3,71%, tasa menor al 4,25% reportada en 2022.

El año pasado, las exportaciones de Santa Cruz alcanzaron un valor de 3.419,5 millones de dólares, y al primer semestre de este año las ventas del departamento suman 1.268 millones.

Se estima que Santa Cruz contribuye con un 31% a 32% al PIB de Bolivia y hoy se consolida como el motor económico del país, gracias a la producción de alimentos, gas natural, ganadería, genética, agroindustria, agricultura, exportación, hotelería, servicios y construcción.

¿Más dinamismo?

Pero ¿qué se necesita para que Santa Cruz pueda multiplicar su dinamismo? Rodríguez sostiene que el sector agropecuario, industrial y forestal pueden dar resultados inmediatos, pero se necesita seguridad jurídica sobre la tierra. Aquello implica garantías para quien arriesga su capital para que pueda planificar el retorno de sus inversiones.

Incluso, el gerente del Ibce señala que el modelo productivo cruceño puede ser la solución a la crisis económica que enfrenta el país y que se manifiesta en la caída de las Reservas Internacionales Netas (RIN), menor disponibilidad de divisas, descenso de la producción y exportaciones de gas natural, y por ende mayor importación de combustibles.

“¿Cómo puede aportar Santa Cruz a la solución? La respuesta es con más dólares, pero para que haya más dólares, qué hago, exportar más, importo menos, traigo capital del exterior con mayor Inversión Extranjera Neta (IED). El problema es que nadie regalará dinero, el riesgo país es alto, si se quiere colocar bonos se debería pagar un interés de 20% y atraer inversión con tanta conflictividad, más bien los capitales salen”, precisa.

Sin embargo, para exportar más se necesita producir más y esto demanda mayor inversión y exige que el país garantice un entorno adecuado.

“Para eso se necesita seguridad jurídica, seguridad de mercado y que el agente económico, el empresario extranjero, local o del interior, tenga la seguridad de ser escuchado en sus demandas y necesidades para activar el potencial del departamento”, añade Rodríguez.

Asegura que la economía regional depende en un 90% de la actividad privada, que se basa en los valores que defendemos, libertad empresarial, competitividad y asociatividad cooperativa y la integración al mundo. “Esto es lo que puede ayudar a Bolivia a salir adelante”, subraya.

Avasallamientos

Otro obstáculo son los avasallamientos. No es posible, dice Rodríguez, que en la actualidad se tengan más de 100 predios tomados, como ocurría en 2013, pero que luego disminuyeron a 10, gracias a acuerdos alcanzados con el Gobierno para retomar la institucionalidad. Esto de cara al compromiso que se tenía de triplicar la producción de alimentos de 15 millones a 45 millones de toneladas.

Se necesita, expresa, frenar las tomas de tierras, porque la actividad agropecuaria y pecuaria o forestal es de alto riesgo, depende de las condiciones del clima, precios y otras contingencias.

Sin cupos para exportar

Además, considera que se necesita dar certeza al inversor de que su esfuerzo podrá traducirse en resultados económicos, porque nadie invertirá para perder o sobreproducir si no podrá exportar.

“En ese sentido, se debe eliminar las restricciones que existen y debe existir libertad de exportación, porque si no se saca a tiempo la producción, se corre el riesgo de que bajen los precios”, subraya Rodríguez.

Falta de infraestructura

El economista Gonzalo Chávez Barrancos considera que para que Santa Cruz pueda crecer más, aumente sus exportaciones, ese departamento debe reducir los costos logísticos, porque no se puede vender más puesto que es caro.

“Por ejemplo, si se pudiera desarrollar una red ferroviaria que nos lleve a puertos de manera segura, se podría rebajar los costos logísticos en más de un 50% el costo de los fletes. Qué significa, si una tonelada de Santa Cruz hacia Arica cuesta 150 dólares, y se lograra bajar por tonelada 70 dólares, imagine el ahorro que existiría; de esa manera la plata se queda con el productor y no con el transportista y se reinvierte en la economía”, recalcó.

“No exportamos más porque los costos son elevados, pero eso es porque no hay la infraestructura de transporte necesaria; tampoco existe infraestructura gasífera y de energía adecuada para montar otras industrias. Si tuviéramos energía de alta tensión en la Chiquitanía, los valles y gas, se podrían llevar muchas industrias a esos lugares y generar mayor desarrollo”, apuntó Chávez.

Junto a ello, está pendiente el desarrollo de Puerto Busch, pero demanda una inversión millonaria, porque se debe construir el puerto e invertir en la infraestructura; asimismo, el HUB de Viru Viru, que era otro proyecto que permitiría la generación de otras industrias de valor agregado. No obstante, el proyecto está postergado.

Otros nichos

Chávez Barrancos sostiene que la economía de Santa Cruz no solo se dinamiza por el sector agroindustrial productivo. Evolucionó desde la producción petrolera, que luego se complementó con el sector agrícola y el ganadero.

“El reflejo es que actualmente exporta más de 300 millones de dólares de la ganadería a través de una empresa (BFC) y la tendencia es que con otras empresas que realizan alta genética, en un plazo de dos a tres años, se pueda exportar mil millones de dólares”, destaca.

Adicionalmente, hay otros sectores que, con los convenios que existen con China, están aprovechando para producir y exportar más chía y sésamo a ese gran mercado y pasar de los 120 o 150 a 500 millones de dólares en tres o cuatro años.

En servicios, muchas empresas se asentaron en el departamento; dos bancos y dos empresas aseguradoras importantes tienen su base en la región. “El resto del país consume gran parte que produce Santa Cruz, y las circunstancias obligan a la tecnificación y a ser mejores; de hecho, la ganadería intensiva que se tenía hace 30 años ya no existe, ahora lo que se tiene es ganadería de alta genética para exportación. Las empresas lecheras han aumentado su calidad y productividad”, remarca.

Santa Cruz también tiene turismo, pero no el receptivo que es la característica, por ejemplo, de Uyuni, sino que la región genera más el turismo de negocios y empresarial. “Es un turismo más para gama media y alta, donde el turista llega, concreta negocios y se va, como por ejemplo Sao Paulo. Hay turismo en la Chiquitanía y los valles, pero es más interno”, subraya.

Para 2025 el PIB cruceño se estima en Bs 47.588 MM

El PIB de Santa Cruz hacia 2025 puede llegar a 47.588 millones de bolivianos (6.937 millones de dólares), según las estimaciones realizadas por Jorge Akamine, presidente del Colegio Nacional de Economistas de Bolivia.

De esa manera, la contribución de la economía cruceña al PIB nacional, que en 2021 fue de 33,9%; en 2022, de 34,1%; en 2023 34,3%, aumentará este año a 34,6% y en 2025, año del Bicentenario, a 35%.

El PIB per capita pasó de 1.835 dólares en 2009 a 4.105 dólares en 2023.

Los volúmenes de producción por grupos de cultivo para la campaña 2021-2022 dan cuenta que el 83,9% de los cultivos cruceños son industriales.

Luego están los cereales que representan el 11,9%, los frutales ocupan el 1,8%, hortalizas el 1,2%, tubérculos y raíces 1,2%. En 2022, Santa Cruz llegó a producir 156.204 toneladas de carne de res.

Es líder en producción, comercio exterior, aportes tributarios, cartera crediticia, empleo productivo y consumo de cemento, y energía eléctrica que se vinculan con las inversiones y la actividad productiva, respectivamente. En dos décadas logró consolidar este liderazgo nacional. Con una superficie que representa el 34% del territorio nacional y con un 24,5% de la población boliviana, es la región de mayor actividad económica y genera cerca de un tercio del PIB del país. La evolución de la economía de Santa Cruz está fuertemente relacionada al incremento de la inversión y en especial la inversión privada productiva.