By Napoleón Pacheco, Brújula Digital:

On the night of Sunday, September 8, President Luis Arce presented himself as the Bolivian Pontius Pilate. Why? He claimed that the reason for the dollar shortage, one of the symptoms of the crisis, was Evo Morales, as he “did not take care” of the “nationalization” since there was no investment in exploration during his administration. However, as Raúl Peñaranda points out, he forgets that he was the Minister of Economy and Public Finance for 12 of Morales’ 14 years in office.

In other words, he washed his hands, as if he had nothing to do with the public investment budgets established annually by the general state budgets, which are drawn up by the ministry he headed and sent to the Legislative Assembly for approval. As the czar of the economy, Arce was in charge of the budget guidelines each year and decided in which sectors of the economy to invest and how much to invest. Even though he was not the Minister of Hydrocarbons, as the head of the economic cabinet, he had the final say.

On the other hand, he claimed that as minister and president, he faced almost the seven biblical plagues: the rise in global food prices, increased container rental costs, global inflation, “El Niño” and “La Niña” phenomena, COVID-19, the private sector’s trade deficit, high oil prices, and, on top of that, the sabotage by the Legislative Assembly, which has not approved $1.076 billion in external credit. In other words, he is a victim of others and circumstances. But he is resisting.

Pontius Pilate added nothing new to what the public already knows about the crisis, and the announcement of the press conference regarding measures to address the dollar shortage created false expectations. There were no measures at all.

When he stated that “the nationalization was not taken care of,” let’s clarify that there was no nationalization. Conceptually, nationalization means expropriation (with compensation) or confiscation (without compensation) of a private asset; the state immediately takes over its management through a state-owned company. Historically, in Bolivia, this was the form and substance of nationalizations in the oil (1937 and 1969) and mining (1952) sectors. On May 1, 2006, there was simply a change of contracts, and foreign companies continued producing oil and natural gas.

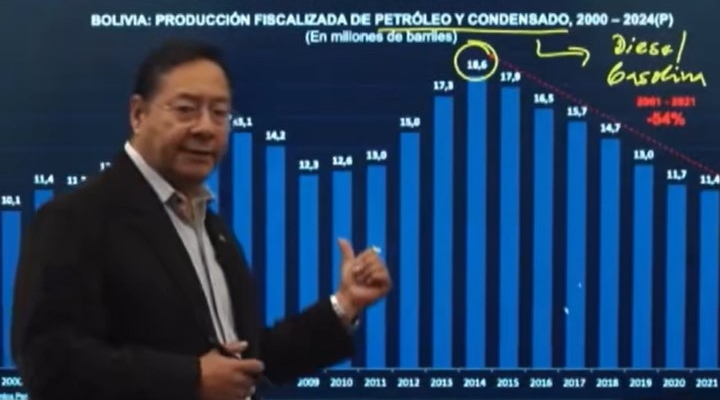

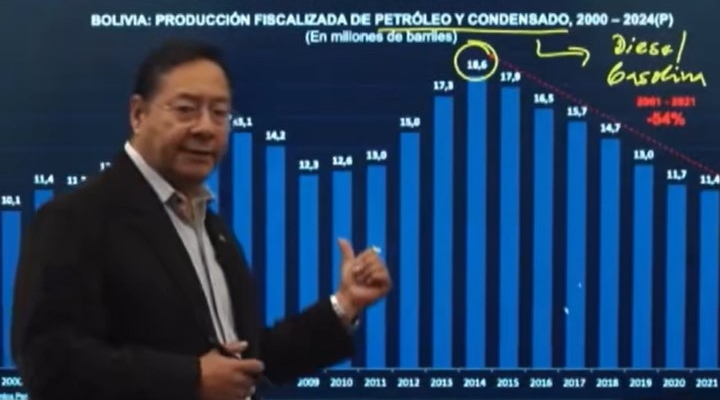

He ignored vital aspects of the crisis, emerging, in his interpretation, from the “nationalization,” such as the excessive “government take.” Even Arce himself said in the past that Bolivia had “the highest gas revenue control in the world, ranging between 74% and 90% of the income of oil companies.” A regime like this, praised by Arce Catacora, is considered aggressive and confiscatory, with “the potential to extinguish risky investments in exploration,” according to the IDB in 2020.

This excessive tax burden, coupled with the contract changes, creates uncertainty and makes it unfeasible for foreign companies, which contribute more than two-thirds of the production of liquids and natural gas, to make risky investments.

He also did not address the fiscal deficit, which since 2014 has been close to 10% of GDP and, at this point, has become structural, unsustainable, and has no clear sources of financing. He did not mention the constant deficits of state-owned companies or the collapse of net international reserves, and consequently, the currency crisis.

He complained about the Legislative Assembly not approving pending loans, calling it internal sabotage; he overlooked the fact that between 2006 and 2007, the G7 forgave 55% of the external debt (it dropped from $4.942 billion in 2005 to $2.298 billion in 2008). Of course, he remained silent about the external debt starting in 2008, during his tenure as Minister of Economy. Under his leadership, external debt rose by 390%, multiplying fivefold (from $2.298 billion in 2007 to $11.268 billion in 2019).

On three occasions, he issued sovereign debt bonds (2012, 2013, and 2017) for a total of $2 billion, causing an increase in the debt balance and payments of principal and interest.

Finally, the anti-crisis policy was absent. His proposal for industrialization with import substitution, a proposal from CEPAL in the 1960s, to save dollars, when state-owned companies are in deficit, is simply a way to increase state employment and, consequently, fiscal spending. Even the administrative measures taken under pressure from businesses have not been fully implemented.

The production of biofuels to replace diesel imports does not seem to yield immediate results. The possible Mayaya field has not yet completed exploratory work. In short, the government, as I have repeatedly stated, does not have a roadmap that at least provisionally establishes the main measures to be implemented and sends a signal of certainty to the public.

What does this mean? The economy will continue to deteriorate. Until when…? Pontius Pilate seems to recall what Keynes said: “In the long run, we are all dead.”

Napoleón Pacheco Torrico is an economist.

Por Napoleón Pacheco, Brújula Digital:

La noche del domingo 8 de septiembre el presidente Luis Arce se presentó como Poncio Pilatos boliviano. ¿Por qué razón? Sostuvo que el culpable de la escasez de dólares, uno de los síntomas de la crisis, es Evo Morales, debido a que no “cuidó” la “nacionalización” ya que en sus gobiernos no se realizó inversión en exploración. Sin embargo, como hace notar Raúl Peñaranda, se olvida que fue ministro de Economía y Finanzas Públicas en 12 de los 14 años de gobiernos de Morales.

En otras palabras, se lavó las manos, como si él no hubiera tenido nada que ver con los presupuestos de inversión pública establecidos por los presupuestos generales del Estado que cada año se elaboran en el ministerio que dirigía y se envían a la Asamblea Legislativa para su aprobación. Como zar de la economía, Arce fue el encargado de las directrices presupuestarias cada año y decidió en que sectores de la economía invertir y cuánto invertir. No obstante que no fue ministro de hidrocarburos, como jefe del gabinete económico tenía la palabra final.

Por otra parte, afirmó que enfrentó como ministro y presidente casi las siete plagas bíblicas. El incremento de precios de los alimentos a nivel mundial, aumento del alquiler de contenedores, inflación mundial, fenómenos de “El Niño” y “La Niña”, el Covid-19, la balanza comercial deficitaria del sector privado, precios del petróleo elevado y, para colmo, sufre el sabotaje de la Asamblea Legislativa que no aprueba 1.076 millones de dólares de crédito externo. Dicho de otra forma, es una víctima de otros y de las circunstancias. Pero, está resistiendo.

Poncio Pilatos no agregó nada nuevo a lo que la ciudadanía conoce respecto a la crisis y por el anuncio que se hizo de la conferencia de prensa en relación a las medidas que implementaría para enfrentar la escasez de dólares, generó expectativas que resultaron falsas. No hubo nada de medidas.

Cuando afirmó que “no se cuidó la nacionalización”, aclaramos que no hubo tal. Conceptualmente, nacionalización significa expropiación (con indemnización) o confiscación (sin indemnización) de un activo privado; inmediatamente el Estado se hace cargo, por medio de una empresa estatal, de la gestión de ese activo. Históricamente en Bolivia esa fue la forma y fondo de las nacionalizaciones en los sectores petrolero (1937 y 1969) y minero (1952). El 1 de mayo de 2006 simplemente hubo cambio de contratos y las empresas extranjeras continuaron produciendo petróleo y gas natural.

Ignoró aspectos vitales de la crisis, emergentes, en su interpretación, de la “nacionalización”, como el excesivo “goverment take”. El mismo Arce dijo en el pasado que Bolivia tuvo “el control de la ganancia gasífera-más altos a nivel internacional, oscilando entre 74% y 90% de los ingresos de las empresas petroleras”. Un régimen, así, alabado por Arce Catacora, es considerado como agresivo y confiscatorio y que tiene “el potencial de extinguir las inversiones arriesgadas en exploración, según consideró el BID en 2020.

Esa carga tributaria excesiva, simultáneamente al cambio de los contratos, genera incertidumbre e inviabilizan la realización de inversiones de riesgo por parte de las empresas extranjeras que contribuyen con más de dos tercios de la producción de líquidos y de gas natural.

Tampoco se refirió al déficit fiscal que desde 2014 se acerca al 10% del PIB, que a esta altura de los acontecimientos volvió a ser estructural, además de insostenible y menos de sus fuentes de financiamiento. No mencionó el constante déficit de las empresas estales e ignoró el desplome de las reservas internacionales netas y, en consecuencia, la crisis cambiaría.

Protestó contra la Asamblea Legislativa que no aprueba créditos pendientes, hecho que calificó como sabotaje interno; desconoció que entre 2006 y 2007 el G7 nos condonó 55% del saldo de la deuda externa (se redujo de 4.942 millones de dólares en 2005 a 2.298 millones de dólares en 2008). Obviamente se calló en cuanto al endeudamiento externo a partir de 2008, con él de ministro de Economía. En su gestión subió la deuda externa en 390%, se multiplicó en cinco veces (de 2.298 millones en 2007 a 11.268 millones de dólares en 2019).

En tres oportunidades, colocó bonos soberanos de deuda (2012, 2013 y 2017) por un total de 2.000 millones de dólares, ocasionando un incremento en el saldo de la deuda y en el pago de capital e intereses.

Finalmente, la política anticrisis estuvo ausente. Su propuesta de industrialización con sustitución de importaciones, propuesta de la CEPAL de la década de 1960, para ahorrar dólares, cuando las empresas estatales son deficitarias, simplemente es una forma de aumentar empleo estatal y, en consecuencia, el gasto fiscal. Ni las medidas administrativas, tomadas por la presión de los empresarios, se acabaron de implementar.

La producción de biocombustibles para sustituir las importaciones de diésel no parece ser de resultados inmediatos. El posible yacimiento de Mayaya aun no completó los trabajos exploratorios. En suma, el Gobierno, como afirmé en repetidas oportunidades, no tiene una hoja de ruta que establezca, por lo menos provisionalmente, las medidas principales a implementarse y que transmita una señal de certidumbre a la ciudadanía.

¿Qué significa lo anterior? La economía continuará deteriorándose. ¿Hasta cuándo…? Poncio Pilatos parece recordar lo que dijo Keynes: “en el largo plazo todos estaremos muertos”.

Napoleón Pacheco Torrico es economista.