Editorial, El Deber:

The dollar and the economy

There is no doubt that the year 1985 marks a profound turning point in Bolivia’s political and economic history for several reasons. The country needed to emerge from a whirlwind of hyperinflation and ungovernability that marked the three stormy years of the government of the Popular Democratic Unity (UDP) whose president, Hernán Siles Suazo, found a painful decline for his long political career.

In those times, democracy was restored with votes and blood, and the economy had to be redirected with adjustments and hunger. There was no other way out. Víctor Paz Estenssoro took on that challenge backed by a strong political coalition in parliament, the Pact for Democracy, which allowed him to implement a series of structural reforms.

Inevitable cuts were necessary, such as the closure of several bankrupt state-owned enterprises or the mass layoffs of miners due to the international collapse of tin prices, which euphemistically was termed as “relocation”. To this day, that entire package of measures is the subject of both positive and negative criticism.

In that context, it is worth mentioning one of the most successful measures: the creation of the dollar auction whose administration was entrusted to the Central Bank of Bolivia, when this institution achieved a high degree of independence and was managed by honest and competent professionals.

The auction allowed the regularization and transparency of the purchase and sale of dollars in the Bolivian market, with daily quotations, reasonable and minimal variations, and clear and transparent information about the amount of dollars that had been bought and sold. The mechanism, simple and efficient, put an end to one of the worst cancers of the economy: the black or parallel market, that dichotomy between the official price and the real price negotiated on the streets, in the hands of currency traders and speculators.

The auction made the market transparent and allowed regular access to the US currency for individuals, importers, and exporters who work daily with the currency that has been, since the mid-20th century, the main global reference. Even in the early years of the successive governments of Evo Morales, with Luis Arce as Minister of Economy, the mechanism remained intact.

But history changed in November 2011 when the Government decided to maintain the fixed exchange rate at Bs.6.96. It is difficult to know whether Minister Arce convinced the president or if it was the other way around, but Bolivia entered a bubble oblivious to the constant ups and downs of the global economy and transitioned from the real exchange rate to the fixed dollar which, for political discourse reasons, was called bolivianization. Furthermore, the Financial Transactions Tax (ITF) was approved and remains in force to this day, which basically penalizes transactions in dollars.

But it is true that bubbles have short lives, especially if, as happened in the Bolivian economy, there was no investment in the development of new gas reserves, the capacity of the productive sector was extremely limited, investment was made in unnecessary and unproductive state-owned enterprises, and international reserves were squandered, maintaining, among other factors, a harmful subsidy for fuels.

Now, Bolivia is in crisis due to a lack of dollars, and denying it is already an offense to common sense. In December 2023, President Luis Arce stated that he was concerned that people continue to trust the dollar. “At some point, that foreign currency will stop having the weight it has today, and gradually that is happening,” he said. Words that, at this point, fall on deaf ears.

For months, the country has been walking on the edge of the precipice, and the Government shows no capacity to achieve political agreements that would preserve the economy and democratic stability. It is not true that the dollar is in free fall, much less.

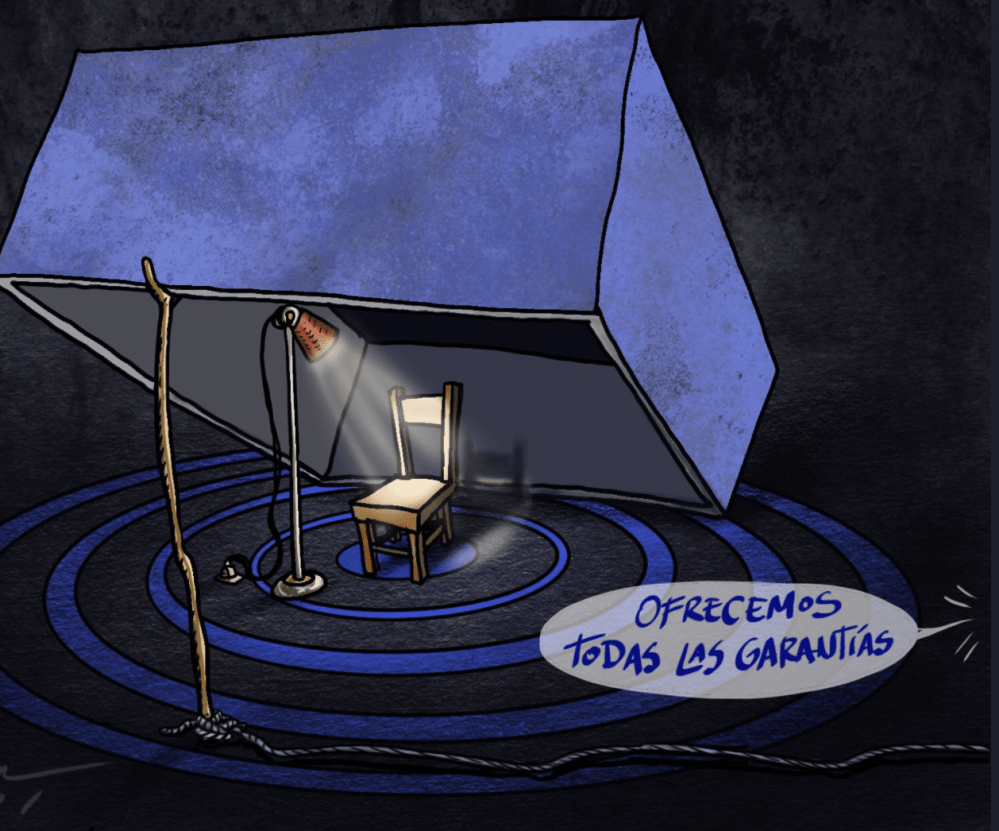

Could it be that the Government insists on maintaining the fixed exchange rate that only exists on the board of the BCB? Perhaps more suitable mechanisms like the auction could work well. Because, hard as it may be to admit, in both liberal and socialist countries, the dollar is regulated by market forces and not by decrees.

El dólar y la economía

No hay duda de que el año 1985 marca una profunda inflexión en la historia política y económica de Bolivia por varias razones. El país necesitaba salir de un remolino de hiperinflación e ingobernabilidad que marcaron los tres tormentosos años de gobierno de la Unidad Democrática Popular (UDP) cuyo mandatario, Hernán Siles Suazo, encontró así un penoso ocaso para su larga carrera política..

En esos tiempos, la democracia se recuperó con votos y con sangre, y la economía se tuvo que reencaminar con ajustes y con hambre. No había otra salida. Víctor Paz Estenssoro asumió ese reto respaldado por una coalición política fuerte en el parlamento, el Pacto por la Democracia, que le permitió viabilizar una serie de reformas estructurales.

Fueron necesarios recortes inevitables como el cierre de varias empresas estatales quebradas o el despido masivo de mineros ante el colapso internacional de los precios del estaño, lo que eufemísticamente fue denominado como “relocalización”. Hasta el día de hoy, todo ese paquete medidas es motivo de críticas positivas y negativas.

En ese contexto, vale la pena mencionar una de las medidas más acertadas: la creación del bolsín del dólar cuya administración quedó en manos del Banco Central de Bolivia, cuando esta institución alcanzó un alto grado de independencia y estuvo en manos de profesionales honestos e idóneos.

El bolsín permitió regularizar y transparentar la compra y venta de dólares en el mercado boliviano, con cotizaciones diarias, variaciones razonables y mínimas e información clara y transparente sobre la cantidad de dólares que habían sido comprados y vendidos. El mecanismo, simple y eficiente acabó con uno de los peores cánceres de la economía: el mercado negro o paralelo, esa dicotomía entre el precio oficial y el precio real que se negociaba en las calles, en manos de librecambistas y especuladores.

El bolsín transparentó el mercado y permitió el acceso regular a la divisa norteamericana para personas particulares, importadores y exportadores que trabajan a diario con la moneda que sigue siendo, desde mediados del siglo pasado, el principal referente mundial. Incluso en los primeros años de los sucesivos gobiernos de Evo Morales, con Luis Arce como ministro de economía, el mecanismo se mantuvo intacto.

Pero la historia cambió en noviembre de 2011, cuando el Gobierno decidió mantener el tipo de cambio fijo a Bs.6,96. Difícil saber si el ministro Arce convenció al presidente o si fue al revés, pero Bolivia entró en una burbuja ajena a los constante altibajos de la economía global y pasó del tipo de cambio real al dólar fijo que por razones de discurso político fue denominado bolivianización. Es más, se aprobó y se mantiene vigente hasta la fecha el Impuesto a las Transacciones Financieras (ITF) que, básicamente, penaliza las transacciones en dólares.

Pero cierto es que las burbujas tienen vida corta y mucho más si, como ocurrió en la economía boliviana, no se invirtió en desarrollo de nuevas reservas de gas, se limitó en extremo la capacidad del sector productivo, se invirtió en empresas estatales innecesarias e improductivas y se dilapidaron las reservas internacionales manteniendo, entre otros factores, una dañina subvención a los combustibles.

Ahora, Bolivia está en crisis por falta de dólares, y negarlo ya es una ofensa al sentido común. En diciembre de 2023, el presidente Luis Arce declaró que le preocupaba que la gente siga confiando en el dólar. “En algún momento, esa moneda extranjera va a dejar de tener el peso que tiene hoy y gradualmente eso está ocurriendo”, afirmó. Palabras que, a estas alturas, caen en saco roto.

Hace meses que el país camina por el borde de la cornisa y el Gobierno no muestra capacidad para lograr pactos políticos que permitan preservar la economía y la estabilidad democrática. No es cierto que el dólar esté en caída libre, ni mucho menos.

¿Será que el Gobierno insiste en mantener el tipo de cambio fijo que solo existe en la pizarra del BCB? Tal vez mecanismos más idóneos como el bolsín puedan funcionar bien. Porque, aunque cueste admitirlo, tanto en países liberales como socialistas, el dólar se regular por las fuerzas del mercado y no por decretos.

https://eldeber.com.bo/edicion-impresa/el-dolar-y-la-economia_358252