By Jorge Soruco, Visión 360:

The country’s privileged geographic location is coveted by criminal groups

Bolivia: a hub for drug production, transit, and distribution for cartels

Cartels from Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and Mexico operate in Bolivia, sparking violence and exposing the lack of international coordination, according to experts.

Cases of cartels in Bolivia. CREATION: Abecor / Visión 360

The scandal broke on Monday, September 8, when Brazil’s O Globo network aired a report revealing that one of the top leaders of the Brazilian criminal organization Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC) had been living in Santa Cruz de la Sierra for 10 years. The report not only triggered a government response but also reinforced the notion that Bolivia has become a hub for drug production, transit, and distribution, according to specialists and former authorities.

They agree that the country’s strategic geographic location allows criminal organizations to move drugs between both ends of the continent. However, government authorities continue to insist that “no international cartels operate in Bolivia,” though they admit emissaries are sent to carry out illicit activities.

“The signs are clear: Bolivia has already been infiltrated by dangerous criminal organizations from Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and Mexico, and this happened a long time ago. To say otherwise is either lying or, worse, refusing to recognize the risks,” said researcher Carlos Börth.

For his part, Carlos Romero, former Minister of Government, recalls that Bolivia’s geographic position and long borders with neighboring countries made it an especially attractive center for drug trafficking. He also warns that “we must not forget this activity fuels and connects with other illicit acts.”

The names and cases are being mentioned more and more frequently: drug-trafficking-related victims executed; people killed using mafia-style methods from the Balkans; PCC and Comando Vermelho leaders from Brazil living lavishly in Bolivian cities; kidnappings in western Bolivia attributed to the Tren de Aragua criminal group, among others.

“We must clarify that there are no cartels in our country. What we see are emissaries who permanently come to promote the business.”

Luis Arce

A useful territory

“What explains the presence of these organizations is that Bolivia has become a sort of distribution center for cocaine and, increasingly, marijuana. In other words, we continue producing cocaine, but we also serve as a transit point for Peruvian coca paste from the VRAEM valley —a very fertile area watered by the Apurímac, Ene, and Mantaro rivers— where coca is produced,” Börth explains.

The specialist goes on to say that the material can be refined in various Bolivian regions or moved to the border with Brazil. There, the load is split between domestic consumption and exports shipped through ports to Europe.

This model emerged due to increased coca production in Colombia and Peru. Romero says that in the first two decades of the 21st century, those two countries controlled 90% of the region’s coca crops, leaving Bolivia “reduced to only 10%.” “That is when the country was reclassified as a transit country,” the former authority states.

The United Nations International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) evaluates territorial situations to determine each country’s status regarding drug trafficking. For its assessments, it considers various factors, including overall criminal activity, the amount of seized controlled substances, and reports from authorities.

In this context, Romero explains that over the past two decades, important regional shifts have occurred. “One relevant factor is that Brazil is no longer just a drug transit country but also one of consumption and trade. Colombia, meanwhile, has basically become the main supplier for the United States, via Mexico and Central America’s Northern Triangle.”

Another factor is the lack of local cartels. Romero explains this is because Bolivia’s population is too small to establish an organization as large and structured as a cartel.

Börth points out that local clans are the formula used by Bolivians. These differ from large foreign groups in that their structure is more informal and horizontal, while a cartel has a rigid, military-like hierarchy: a leader commanding captains, who in turn oversee soldiers of different ranks.

“In a couple of months, a new government will take office. The decisions it makes will determine whether Bolivia reaches the levels of violence seen in Colombia or Ecuador.”

Carlos Börth

This has increased interest in the region. Adding to this is the arrival of groups from the Balkans, a geopolitical area in southeastern Europe encompassing countries such as Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia—primarily Albanians.

The installation of cartels follows a process similar to how international corporations expand abroad. “When a foreign industry settles in Bolivia, Peru, or elsewhere, it always seeks local collaboration. That is inevitable, because locals know the information, the context, the geography, the psychology, etc. That is why, at first, foreign criminal organizations operate jointly with Bolivian family clans, who act as suppliers and intermediaries between foreign bosses and coca growers,” Romero explains.

However, this does not mean an equal partnership. The cartels call the shots, while the local clans only provide specific services. If they fail, violence is usually the swiftest—and often the only—response.

Rising violence

Wherever a drug-trafficking circuit is established, violence inevitably follows. From robberies to massacres, the signs of cartel activity are now visible in Bolivia.

“In the last four years, we’ve seen more cases of contract killings than at any other time in our history,” Romero laments. Börth warns that the country is facing an escalation of aggression, raising fears that Bolivia could soon resemble Ecuador or Mexico.

The process is similar across much of the continent: first comes the turf war between foreign gangs and local groups; then, score-settling and punishments handed down by high-ranking “officers” to their “soldiers,” drug dealers, or transporters.

Soon after, the dead become casualties of cartel wars, as seen in conflicts between Brazil’s PCC and Comando Vermelho, or among different Balkan factions.

The next level is attacks against police, judicial, regional, and national authorities, as well as journalists and social leaders who refuse to be bought. “That’s what we saw in Colombia during Pablo Escobar’s era, and what we’re now witnessing in Ecuador, where the military was overwhelmed by Albanians,” Börth notes.

This escalation is both circumstantial and strategic. “Drug trafficking is obviously driven by violence. Right now, Latin America holds 9% of the world’s population but accounts for between 42% and 44% of global violence, most of it tied to narcotics,” Romero states.

“To reproduce itself, drug trafficking needs violence, which grows exponentially. Once criminal organizations consolidate their presence in a territory, they divide up the routes and strategic areas, and then begin regulating criminal behavior to divert law enforcement’s attention,” he adds.

That means other forms of crime—kidnappings, robberies, human trafficking—are directed by cartel leaders to scatter the state’s security forces. This stretches government resources thinner, giving drug traffickers more freedom of movement.

“Cartel activity has always existed in Bolivia, to a greater or lesser extent. In the 1980s, Cali and Medellín cartels set up cocaine labs in Beni.”

Carlos Romero

This goes hand in hand with the loss of control in certain regions where cartels are entrenched. Experts point to parallels: Argentina lost control of Rosario; Chile had to militarize its northern border with Bolivia and Peru after police were overwhelmed; and Mexico was forced in 2021 to release a drug trafficker under cartel pressure.

In Bolivia, cartel presence is most evident in the Tropic of Cochabamba—both a hotspot for drug traffickers and the political stronghold of former president Evo Morales—and in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, where several PCC bosses lived under false identities and where cases linked to Albanian mafias have been documented.

Last week, authorities even labeled Santa Cruz a “sanctuary city”—a refuge for fugitives from abroad seeking to “cool off,” lying low to avoid capture while enjoying a life of luxury.

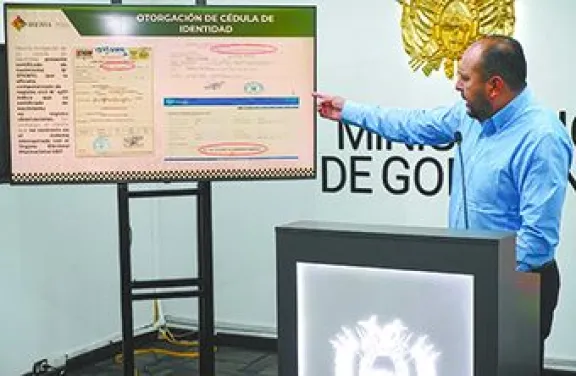

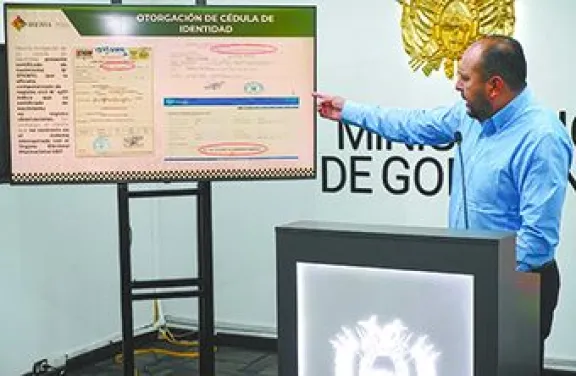

So far this year, three PCC bosses have been identified in such situations. The first was Marcos Roberto de Almeida, alias Tuta, arrested in May after a Segip official reported that he was trying to renew an ID card under a false name.

The second was Alex Heleno Da Silva, arrested in August when Bolivian police found 54 grams of marijuana in his possession during a search.

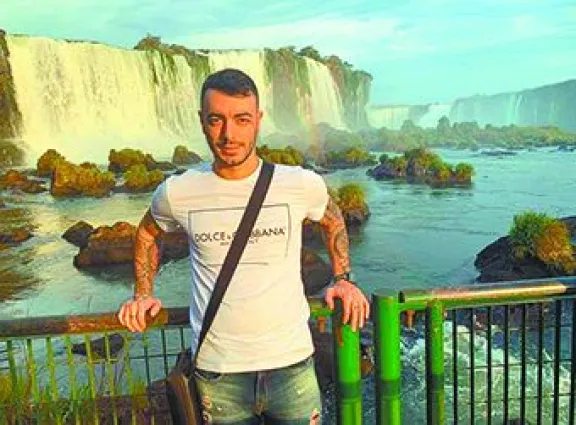

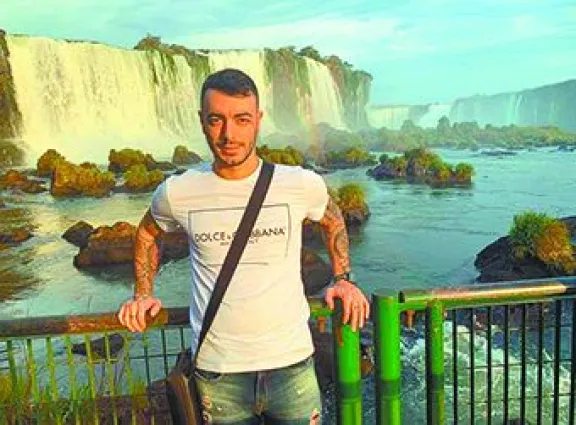

The third case was uncovered on Monday, September 8, in O Globo’s exposé, which revealed that Sérgio Luiz de Freitas Filho, alias Mijão, a PCC boss, had lived in Bolivia for a decade.

Another is Sebastián Marset, leader of the First Uruguayan Cartel, who also hid in Santa Cruz and even played for a local soccer team.

Yet the government of Luis Arce continues to deny cartel presence. Minister of Government Roberto Ríos insists that what exists are merely “emissaries.”

Experts strongly disagree. “Cartel activity has always existed in Bolivia, to a greater or lesser extent. In the 1980s, Cali and Medellín cartels set up cocaine labs in Beni,” Romero argues.

Börth also recalls that in that decade, Jorge Roca Suárez, better known as Techo de Paja, tried to form his own cartel but failed. He adds that current organizations gained a strong foothold about 15 years ago, during Evo Morales’ administration.

On the edge

Experts warn this has left the country on the brink. “In a couple of months, a new government will take office and will have to face the situation. Whether Bolivia reaches the level of violence now seen in Colombia, Mexico, or Ecuador will depend on the decisions it makes,” Börth cautions.

Romero stresses that the issue must be tackled structurally. “It’s not enough to attack only the symptoms. Joint action with neighboring countries is essential, since this is a regional problem. And because of the infiltration of European mafias, it’s also necessary to coordinate with Europol to design a better strategy.”

Joint actions must be established with the authorities of neighboring countries, as this is a regional problem. Furthermore, due to the infiltration of European mafias, it is necessary to contact Europol to design a better strategy.

Part of the problem is that Peru and Brazil have an excessively long border, exceeding 5,000 kilometers. This means that the boundaries are riddled with weak points.

Shootouts and executions: an imported crime model

Between August and September, more than a dozen people were killed in public shootings in El Alto (La Paz), Guayaramerín (Beni), and Santa Cruz, as well as in communities like Entre Ríos in the Tropic of Cochabamba.

These contract killings were marked by extreme violence: attackers, often ambushing victims from vehicles, emptied entire magazines into their targets. In one Santa Cruz case, an autopsy revealed a victim had been hit by 100 bullets.

Experts such as criminologist Gabriela Reyes and Colonel Jorge Toro argue that this type of crime signals the involvement of foreign criminal organizations. “It’s an imported model,” Reyes told Visión 360.

Toro added that these attacks go beyond eliminating a target—they seek to completely destroy it. “When you fire that many rounds into one person, the attacker’s goal isn’t just to kill. It’s to ensure death 100% and cause maximum destruction. With a hundred bullets, the body is shredded,” he warned.

This trend also includes physical and psychological torture. Some victims were beaten to death, while others were executed in their own territory—clear signs of escalating violence.

EVIDENCE

REPORT. Vice Minister of Social Defense and Controlled Substances Jaime Mamani stated that during his administration, 38 foreigners were expelled, some of them members of Brazil’s Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC). He also affirmed that emissaries of this criminal organization have been entering Bolivian territory since 1997, meaning for more than 28 years.

URUGUAY. Sebastián Marset, the self-proclaimed “King of the South,” is Uruguay’s most notorious criminal. In 2022 he settled in Santa Cruz, where he even played soccer for a professional team.

BRAZIL. Sérgio Luiz de Freitas Filho, a PCC member, entered Bolivia irregularly and in 2011 married a Bolivian citizen to obtain naturalization. With forged documents, he secured a national ID card in 2014, along with a driver’s license.

IDENTITY. In May, Marcos Roberto de Almeida, alias Tuta, was arrested in Santa Cruz after attempting to renew an ID card under a false name.

Por Jorge Manuel Soruco Ruiz, Visión 360:

La privilegiada ubicación geográfica del país es codiciada por los grupos criminales

Bolivia, un hub de producción, tránsito y distribución de drogas para los cárteles

Cárteles de Brasil, Colombia, Ecuador y México operan en Bolivia, provocando violencia y evidenciando la falta de coordinación internacional, según especialistas.

Los casos de carteles en Bolivia. CREACIÓN: Abecor / Visión 360

El escándalo estalló el lunes 8 de septiembre, cuando la red O Globo de Brasil transmitió un reportaje en el que denunció que uno de los principales jefes de la organización criminal brasileña Primer Comando de la Capital (PCC) vivía en Santa Cruz de la Sierra desde hacía 10 años. El reporte no solo provocó la movilización de las autoridades, sino que también cimentó la idea de que Bolivia se ha convertido en un hub (centro, en inglés) de producción, tránsito y distribución de drogas, según especialistas y exautoridades.

Ellos coinciden en que la privilegiada ubicación geográfica del país permite que las organizaciones criminales transporten droga entre ambos extremos del continente. Sin embargo, las autoridades de Gobierno insisten en que “en Bolivia no operan cárteles internacionales”, aunque sí envían emisarios para desarrollar sus actividades ilícitas.

“Las señales son claras: Bolivia ya ha sido infiltrada por peligrosas organizaciones criminales de Brasil, Colombia, Ecuador y México, y esto ocurrió hace bastante tiempo. Decir lo contrario es mentir o, peor aun, no reconocer los riesgos”, sostiene el investigador Carlos Börth.

Por su parte, Carlos Romero, exministro de Gobierno, recuerda que la posición geográfica de Bolivia y sus extensas fronteras con países vecinos la convirtieron en un centro especialmente atractivo para el narcotráfico y además advierte que “no hay que olvidar que esta actividad impulsa y se relaciona con otros hechos ilícitos”.

Los nombres y los casos se mencionan con cada vez mayor frecuencia: víctimas acribilladas relacionadas con el tráfico de drogas; personas asesinadas por modalidades propias de las mafias de los Balcanes; jefes del Primer Comando de la Capital (PCC) y del Comando Vermelho, de Brasil, que viven con lujo en ciudades bolivianas; secuestros en el occidente del país atribuidos a la organización criminal Tren de Aragua, entre otros.

“Hay que aclarar que no hay presencia de cárteles en nuestro país. Se trata de emisarios que vienen permanentemente promocionando el negocio”.

Luis Arce

Un territorio útil

“Lo que explica la presencia de estas organizaciones es que Bolivia se ha convertido en una especie de centro de distribución de cocaína y, cada vez más, de marihuana. Es decir, seguimos produciendo cocaína, pero también servimos de tránsito para la pasta base peruana proveniente del valle del Vraem —una zona muy rica, regada por los ríos Apurímac, Ene y Mantaro— donde se produce coca”, asegura Börth.

El especialista continúa revelando que el material puede ser refinado en distintas regiones bolivianas o trasladado a la frontera con Brasil. En ese país, la carga se divide entre la destinada al consumo interno y la que se envía a los puertos para ser transportada a Europa.

Esta modalidad surgió debido al incremento en la producción de coca en Colombia y Perú. Romero dice que, en las dos primeras décadas del siglo XXI, ambos países controlan el 90% de los cultivos de la región, dejando a Bolivia “reducida solamente a un 10%”. “Es en ese momento que el país es reclasificado como país de tránsito”, indica la exautoridad.

La situación de los territorios es evaluada por la Junta Internacional de Fiscalización de Estupefacientes (JIFE) de las Naciones Unidas, encargada de identificar la condición de los países en relación con el narcotráfico. Para estas evaluaciones, analizan diferentes factores, que incluyen la actividad criminal general de la nación en cuestión, la cantidad de sustancias controladas decomisadas e informes de las autoridades.

En ese sentido, Romero explica que, en las dos últimas décadas, se han producido cambios importantes en la región. “Un factor relevante es que Brasil ya no es solamente un país de tránsito de drogas, sino también un país de consumo y comercio. Colombia, por su parte, se ha convertido básicamente en el principal proveedor para Estados Unidos, a través de México y el Triángulo Norte de Centroamérica”.

A ello se suma la ausencia de grupos locales. Esto se debe, según explica Romero, a que la población boliviana es demasiado reducida como para establecer una organización tan grande y estructurada como un cártel.

Börth señala que los clanes familiares son la fórmula utilizada por los nativos. Estos se diferencian de los grandes grupos del exterior en que su organización es más informal y horizontal, mientras que un cártel cuenta con una estructura rígida de tipo militar: un líder que comanda a capitanes, quienes, a su vez, dirigen a soldados de distintos rangos.

“En un par de meses, un nuevo Gobierno dirigirá el país. De las decisiones que tome dependerá si se alcanza el nivel de violencia que existe en Colombia o Ecuador”.

Carlos Börth

Esto ha hecho que el interés en la región aumente. A ello se suma la llegada de fuerzas provenientes de los Balcanes, región geocultural del sureste de Europa que abarca países como Albania, Bosnia y Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croacia, Grecia, Macedonia del Norte, Montenegro, Serbia y Eslovenia, principalmente de Albania.

La instalación de los cárteles sigue un proceso similar al de la construcción de subsidiarias de empresas internacionales legales. “Cuando una industria de un país extranjero se asienta en territorio boliviano, peruano o de cualquier otro lugar, siempre va a buscar colaboración local. Eso es inevitable, porque son las personas que manejan la información, el contexto, conocen la geografía, la psicología, etcétera. Por eso, al principio, las organizaciones criminales extranjeras operan conjuntamente con clanes familiares bolivianos, que sirven tanto de proveedores como de intermediarios entre los capos extranjeros y quienes cultivan coca”, explica Romero.

Sin embargo, esto no es señal de una asociación equitativa. Quienes realmente mandan son los cárteles, mientras que los clanes familiares solo proveen servicios específicos. Y, si no cumplen, la violencia suele ser la respuesta más rápida y, muchas veces, la única.

Incremento de la violencia

Y es que, cuando se establece un circuito de narcotráfico, la violencia siempre le sigue. Desde robos hasta masacres son señales claras de la actividad de los cárteles en las regiones, como ocurre actualmente en Bolivia.

“En los últimos cuatro años hemos experimentado más casos de sicariato que en cualquier otro periodo de nuestra historia”, lamenta Romero. Por su parte, Börth advierte que se está viviendo una escalada de agresiones, al punto de temer que el país llegue a una situación similar a la que enfrentan Ecuador y México.

El proceso es similar en muchas partes del continente: primero viene la disputa por el territorio entre las bandas extranjeras y las locales; luego, los ajustes de cuentas y los castigos impuestos por los “oficiales” de mayor rango a los “soldados”, vendedores de droga o transportistas, entre otros.

Posteriormente, los muertos se convierten en víctimas de la guerra entre los cárteles extranjeros. Esto ocurre, por ejemplo, en el conflicto que existe entre el PCC y el Comando Vermelho, de Brasil, o entre las diferentes nacionalidades balcánicas.

El siguiente nivel es el ataque a las autoridades policiales, judiciales, regionales y nacionales, así como a periodistas y dirigentes de organizaciones sociales que no fueron compradas. “Es lo que se vio en Colombia en la época de Pablo Escobar, o lo que vemos actualmente en Ecuador, donde el Ejército fue rebasado por los albaneses”, dice Börth.

Esta escalada responde tanto a las circunstancias como a la estrategia. “El narcotráfico, obviamente, se maneja con violencia. En este momento, en Latinoamérica vive el 9% de la población mundial, pero concentra entre el 42% y el 44% de la violencia mundial, que se articula, fundamentalmente, en torno a los estupefacientes”, indica Romero.

“Para reproducirse, el narcotráfico necesita violencia, que es exponencial, porque se produce una vez que las organizaciones criminales han consolidado su presencia en un territorio, se han distribuido entre ellas las rutas y las áreas estratégicas y, así, comienzan a regular el comportamiento criminal para desviar la atención de las autoridades”, añade.

Es decir, que las otras formas de criminalidad son dirigidas por los capos para dispersar el esfuerzo de la fuerza pública del Estado. Los secuestros, los atracos, el tráfico de personas… todos sirven para que el Gobierno estreche cada vez más sus recursos en la lucha contra el crimen y, así, los “narcos” tengan mayor libertad de movimiento.

“Siempre hubo actividad de cárteles en Bolivia, en mayor o menor medida. En los años 80, Cali y Medellín instalaron fábricas de cocaína en Beni”.

Carlos Romero

A ello se suma la pérdida de control en regiones específicas del país, donde los cárteles tienen mayor presencia. Así, coinciden los especialistas, Argentina perdió el control de Rosario; Chile se vio obligado a militarizar la frontera norte con Bolivia y Perú, debido a que los carabineros fueron sobrepasados; y México enfrenta problemas en su región norte, llegando al punto de tener que ordenar la liberación de un narcotraficante en 2021.

En Bolivia, las señales de una mayor presencia de cárteles se manifiestan en el Trópico de Cochabamba, una zona particularmente conflictiva tanto por la actividad de narcotraficantes como por ser el bastión del expresidente Evo Morales; así como en Santa Cruz de la Sierra, ciudad donde varios capos del PCC viven con identidades falsas y donde también se han registrado casos de violencia atribuidos a mafias albanesas, según investigaciones.

Santa Cruz, incluso, fue denominada la semana pasada como una “ciudad santuario” por las autoridades. Es decir, un territorio donde los fugitivos de otros países pueden refugiarse para “enfriarse”, un lapso en el que un criminal suspende su actividad ofensiva para evitar la captura y llevar una vida de lujos.

Solo este año se identificaron tres capos del PCC en esa situación. El primero fue Marcos Roberto de Almeida, conocido con el alias de “Tuta”, detenido en mayo después de que un funcionario del Servicio General de Identificación Personal (Segip) denunciara que intentaba renovar un carnet de identidad con un nombre falso.

El segundo fue Alex Heleno Da Silva, detenido en agosto cuando, durante una requisa, funcionarios de la Policía Boliviana encontraron 54 gramos de marihuana en su poder. ç

Y el tercero fue descubierto el lunes 8 de septiembre, gracias a un reportaje de la red O Globo. La nota reveló que Sérgio Luiz de Freitas Filho, alias “Mijão”, capo del PCC, vivió una década en el país.

También está el caso de Sebastián Marset, jefe del Primer Cártel Uruguayo, que se refugió en Santa Cruz; llegó incluso a jugar en un equipo de fútbol de ese departamento.

Sin embargo, el gobierno de Luis Arce continúa negando la presencia de cárteles. El ministro de Gobierno, Roberto Ríos, aseguró que lo que existe son “emisarios”.

Algo que los especialistas refutan. “Siempre hubo actividad de cárteles en Bolivia, en mayor o menor medida. En los años 80, Cali y Medellín instalaron fábricas de cocaína en Beni”, afirma Romero.

Börth también recuerda que, en esa década, Jorge Roca Suárez, más conocido como “Techo de Paja”, intentó formar su propio cártel, aunque no lo logró. Añade que las actuales organizaciones ingresaron con fuerza hace unos 15 años, durante el gobierno de Evo Morales.

Situación al borde

Eso, aseguran los especialistas, deja al país al borde de un precipicio. “En un par de meses, un nuevo Gobierno dirigirá el país y tendrá que hacer frente a la situación. Dependerá de las decisiones que tome si llegamos al nivel de violencia que se observa en Colombia, México o Ecuador”, advierte Börth.

Por su parte, Romero indica que el problema debe abordarse con una visión estructural. “No basta con atacar solo los síntomas.

Se deben establecer acciones conjuntas con las autoridades de los países vecinos, ya que es un problema regional. Incluso, debido a la infiltración de las mafias europeas, es necesario contactar con Europol para diseñar una mejor estrategia”.

Parte del problema es que, con Perú y Brasil, se tiene una frontera demasiado extensa, que supera los cinco mil kilómetros. Esto provoca que los límites estén llenos de puntos débiles.

Ejecuciones con balaceras, una modalidad de crimen importada

Entre agosto y septiembre, más de una decena de personas perdieron la vida en ataques con armas de fuego en espacios públicos de las ciudades de El Alto (La Paz), Guayaramerín (Beni) y Santa Cruz, además de en comunidades como Entre Ríos, en el Trópico de Cochabamba.

Estos actos de sicariato se caracterizaron por su extrema violencia, en la que los atacantes, generalmente personas que emboscaban a sus víctimas desde vehículos, vaciaban los cargadores de sus armas de fuego. En uno de los casos ocurridos en Santa Cruz de la Sierra, la autopsia reveló que una de las víctimas recibió 100 impactos de bala durante el ataque.

Especialistas como la criminóloga Gabriela Reyes y el coronel Jorge Toro indicaron que este tipo de crímenes es señal de la actuación de organizaciones criminales extranjeras en el país. “Es una modalidad importada”, aseguró Reyes en una entrevista con Visión 360.

Toro, por su parte, indicó que este tipo de ataques no se limitan a eliminar al objetivo, sino a destrozarlo lo más completamente posible. “Cuando disparas tantas balas contra un blanco concreto, el atacante no piensa solo en eliminar a su víctima. Lo que realmente busca es asegurarse al 100% de su muerte, causando la mayor cantidad de daño posible. Y con un centenar de impactos de bala, el blanco queda destrozado”, advirtió.

A esto se suma la tortura, tanto física como psicológica. Hay casos de personas ultimadas mediante golpes, así como de quienes fueron ejecutadas en su propio territorio, lo que evidencia una escalada de violencia.

PRUEBAS

INFORME. EL viceministro de Defensa Social y Sustancias Controladas, Jaime Mamani, aseguró que durante su gestión se expulsó a 38 extranjeros, algunos de los cuales formaban parte del Primer Comando Capital (PCC). Además, afirmó que emisarios de esta organización criminal brasileña ingresan a territorio nacional desde 1997, es decir, desde hace más de 28 años.

URUGUAY. Sebastián Marset, el autoproclamado “Rey del Sur”, es el delincuente más notorio de Uruguay. En 2022 se estableció en Santa Cruz, donde incluso jugó fútbol en un equipo profesional.

BRASIL. Sérgio Luiz de Freitas Filho, miembro del PCC, ingresó de manera irregular a Bolivia y en 2011 se casó con una ciudadana boliviana para naturalizarse. Obtuvo, con documentos falsos, su cédula de identidad en 2014, así como su licencia de conducir.

IDENTIDAD. En mayo, Marcos Roberto de Almeida, alias “Tuta”, fue detenido en Santa Cruz, tras intentar renovar un carnet con un nombre falso.