By Luz Mendoza, Eju.tv:

Summary Procedure: Innocents Forced to Accept Guilt to Stop Judicial Predation

It often happens that due to the “evident miseries” of Bolivia’s penal system, after a series of unsuccessful attempts by the accused to prove their innocence —which they are not obligated to do—, faced with the system’s indifference and usually while being detained, they have no choice but to plead guilty in an attempt to obtain some benefit.

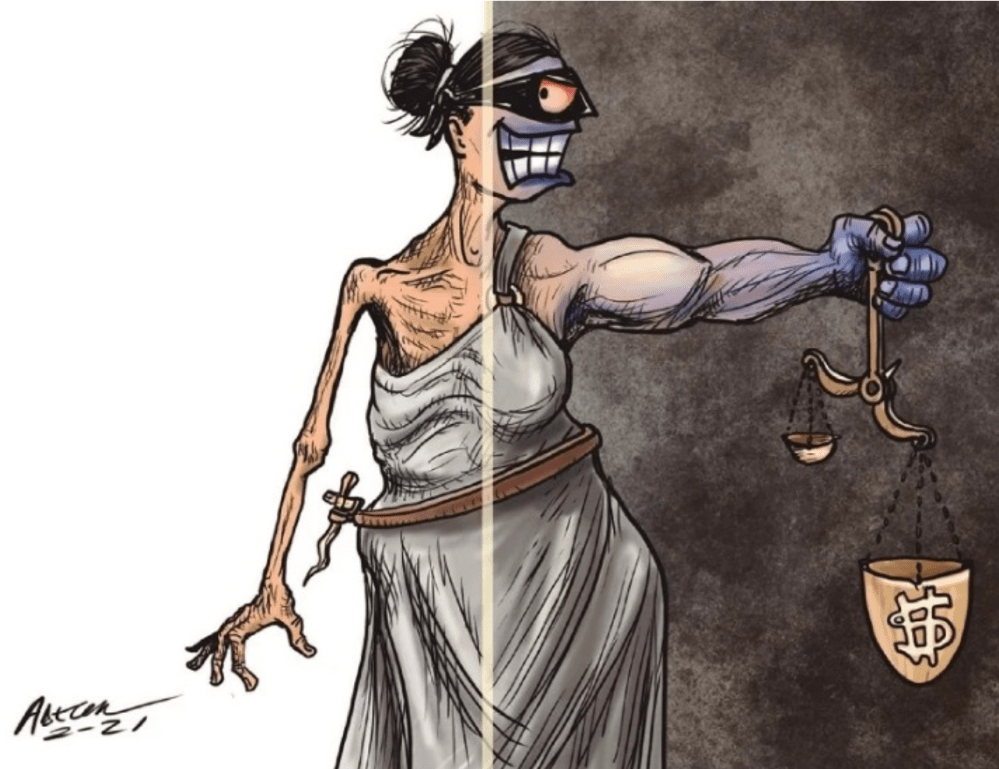

Illustrative photo: FP

La Paz, April 8, 2024 (ANF).— “It doesn’t matter if you’re innocent, there’s a dead person here and we can’t set you free,” was the response of the presiding judge of the tribunal to Felipe, who, finding himself penniless, turned to him, desperate, to put an end to a judicial process that had taken years, strength, and life from him over a decade.

He was in debt and jobless. His lawyer kept calling, demanding money, more money, “even though he did nothing or very little.” He went to the ATM and found nothing, not even for bus fare. For days, he had been eating very little, whatever was available. Worry consumed him. Attending hearings at any moment was a torment that shattered his peace of mind.

“I am innocent and I can prove it, but I have no money left, and I’m tired, I no longer have the desire to read through the volumes of the case file,” he confronted the judge.

Felipe says that after so many years, picking up the same legal texts, which he had held in his hands repeatedly to read and reread, became tedious, “you lose interest,” besides the possibility that it could all be in vain.

He studied law while imprisoned. As an eager student of knowledge, he spent days and nights reviewing and understanding the codes, trusting that the law was a guarantee of order and justice to defend his innocence. The pressure was so intense that he suffered a stroke. All in vain. The disillusionment was brutal.

“It’s better for you to go for the abbreviated process or we’ll give you 30 years, it doesn’t matter if you’re innocent, because there’s a dead person here, we can’t set you free, so much time has passed already, because if not, my head is also on the line,” replied the presiding judge.

Felipe says that if he were found innocent, the prosecutors and judges would have to compensate him for all the harm they caused him by keeping him imprisoned for so many years. He planned to sue them, but now, with diminished spirits and health, it was more difficult.

Debt-ridden and unemployed, what did he prefer? Continuing to pay a lawyer or feeding his family or himself? He had to choose. He had to make a decision. He says that the financial aspect was a significant factor in opting for the abbreviated process.

With much pain, after so many years of struggling to exit the process and be freed, seeing how much his family had fought for him, “it was tough to realize that all the struggle had been in vain.”

“It was very sad for me to say because they make you read, ‘you take responsibility for this act,’ and to say yes without having done it, I think it was one of the most difficult moments I’ve had in life, and also for my family, they were all crying, after so much fighting, I had to finally bow my head to submit to this corrupt system.”

Felipe was accused of the death of a young man in 2014, without having been at the scene and with scientific evidence concluding that the DNA found under the victim’s nails, from the self-defense, did not belong to him, but to an unidentified third person. In 2017, he was sentenced to 30 years in prison without the possibility of parole in the San Pedro prison, but three years later the process was reset due to serious judicial aberrations. A new trial was ordered.

Arturo Yañez Cortez, a renowned jurist, wrote in his column “Summary Procedure, Equal to Guilt?” that this admission of guilt, where the accused “puts the noose around his neck by accepting an immediate sentence,” does not always mean that he is guilty in reality, since many factors can lead the accused, still innocent, facing the disaster of the criminal process, to have no choice but to plead guilty.

He said that among them it often happens that due to the “evident miseries” of the Bolivian penal system, after a series of unsuccessful attempts by the accused to prove their innocence —which they are not obligated to do—, faced with the system’s indifference and usually while being detained, they have no choice but to plead guilty in an attempt to obtain some benefit. “A criminal process, worse if it involves detention, asset seizure, expenses, separation, and frequently abandonment of the family, social stigma, etc., almost irretrievably destroys the life project of any human being.”

“Give me fewer years if I opt for the abbreviated process, so I won’t go back to jail,” Felipe told the presiding judge.

Felipe had been in the judicial process for 10 years, six of which he had spent in jail. Submerged in poverty, with his life project destroyed, he saw the abbreviated procedure as the only option to put an end to so much suffering. But the suffering did not end. The presiding judge wanted to capitalize on the last breath of a dying and desperate soul.

The presiding judge proposed 20 years, but “if you have $5,000, we can reduce the years to end it all once and for all,” Felipe recalls the official telling him.

The nightmare of money resurfaced, the presiding judge “was like a merchant seeking to profit from everything, even from the scraps, I didn’t think they also asked for money in the abbreviated process.”

“If I had that money, I would continue with the trial, but that’s what I don’t have,” he replied.

“Try to get it, there are three of us, it’s not just my head,” the judge retorted, making him understand that it’s a group effort, like a mafia, which after a hit must distribute the money among all.

The presiding judge didn’t care if he imprisoned an innocent person or released a murderer, he just wanted money or for his fatigued reality of reviewing mountains of files in a judicial system overwhelmed by thousands of cases to end.

“Besides, I’m tired of going through all this again, I have so many cases and going through your file again, it would be a relief for us if you opt for the abbreviated process and that’s the end of it,” said the judge, maintaining the proposal of 20 years in prison hoping that Felipe would accept to pay something.

“But I’ll have to go back to jail if you give me 20 years.”

“Of course, but it will only be a few years and you’ll come out with money, inside I know they come out with more money, I know how it is in there.”

Judges like the presiding judge turn justice into a customizable product, where sentences, regardless of their severity, have a price, as revealed in the case of the femicide Richard Choque who paid in 2015 to the judge of penal execution Rafael Alcón Aliaga $3,500 and a bottle of whiskey so that, through a legal ruse, he would be set free.

“You think I’m a criminal, sure, for a criminal who is used to it, it’s fine, but my life’s desire is not that, it’s not to be in jail and commit crimes,” he questioned. Seeing that he couldn’t get anything from Felipe, the presiding judge sentenced him to 15 years in prison.

Article 373 of the Code of Criminal Procedure states that once “the investigation is concluded, the prosecutor in charge may request from the investigating judge, in his conclusive request, the application of the abbreviated procedure.”

And, for it to be appropriate, “the agreement of the accused (without any pressure) and his defender must be obtained, which must be based on the admission of the fact and his participation in it,” that is, admitting to the responsibility of the crime.

Felipe recalls that the justice system always suggested the abbreviated process, from his apprehension, without having investigated anything. Police officers, prison officials, lawyers, prosecutors, at all times brought up the topic.

“In my case, the prosecutor and some lawyers came indicating that I should opt for the abbreviated process, from the moment they arrested me. I said why should I go for the abbreviated process, why should I take the blame for something I didn’t do, but everyone tells you to go for the abbreviated process, even the police officers, and many people fall for it.”

Overcrowding

The abbreviated procedure is used to reduce prison overcrowding levels, save resources, and even attempt to show quick and effective “results.” Felipe says it’s for the authorities to “wash their hands” and be able to “rid themselves of any doubts about their suitability,” so “for them, it’s simple to ask for it,” because “they don’t see you as a person, but as a number.” According to the Final Public Accountability Report of the Supreme Judicial Tribunal, in 2023, after hearings in seven prison facilities, 134 detainees opted for the abbreviated procedure. Felipe recalls that, in his case, after so many years, he had to do the same.

“All this is a terrible economic expense and personally, it has been totally destructive to my economy, to my way of life, even.”

So many years of trudging along the winding path of the judicial system has changed his perspective. At first, he believed that the judge was a qualified person, superior, very well educated, wise —that’s why they are called Your Honor—, but getting to know the system up close has given him a more complete understanding. He says they are full of prejudices, they are guided by appearances, and they do not respect the law they claim to apply and defend. He bursts into laughter when he hears officials from the Public Ministry say that the Prosecution is one of the institutions with the “highest prestige.”

“They talk a lot about ethics, but they already judge you by your skin color, by your religion, by your musical tastes, or by how you dress; they assume a lot, they say: he is (guilty), it’s obvious, have you seen his eyes, his look, things like that, ridiculous to our understanding, they are not professional at all.”

In the first sentence, the technical judges who sentenced him did not consider the DNA evidence that acquitted him, but rather his doctrine of anti-Christian rock musician and concluded that “he despises life” and therefore is guilty.

Felipe is convinced that justice is a business, he knows it from the inside, and to any person with a legal problem who asks him what can I do, he responds: If you have money, pay the prosecutor or the judge and that’s it.

“One believes that the lawyer will help, that what he says is the truth, but in the end, you realize that it’s not like that, that it’s all a business,” he says and recalls that his first lawyer promised to get him out in six months, but took his only four thousand dollars and disappeared.

Justice has taught him that between hiring a lawyer who knows the procedure and another who is tricky, it is preferable to opt for the one who does tricks, he will get you out, because with the other “you will be walking for years and in the end, you will end up in the same place that the tricky one will tell you.”

“I no longer believe in the ability of a lawyer, rather I believe in how virtuous it is to give talks or do things outside the law, because wanting money is common among them, prosecutors, and judges.”

The only peace of mind he gets from having opted for the abbreviated process is that he will no longer attend hearings or think about finding money to give to the lawyer and pay fees in the corrupt system. But an immense social and moral weight will accompany him forever. No one knows his motivations for choosing the abbreviated process, only he and his family.

“All the people who now read or find out that I went for the abbreviated process say: ‘it must have been true, that’s why he went for the abbreviated process, he must have been guilty,’ that’s what most people who know me think, they don’t say that I didn’t have money and was forced to do it, the ordinary person doesn’t know well that poison that is the judicial system.”

His morals were completely affected. A person with principles and values, with a tranquil life, a profession, and a project, by accepting to have committed something so terrible, after “doing everything possible to prove my innocence,” feels an immeasurable loss.

“I naively thought that the Criminal Procedure Code was useful, but it isn’t. And now I wonder why I had to go through all of this, why all this suffering, even financially, sometimes I have nothing to eat, why I had to endure so much and even accept guilt, to say ‘I am the guilty one’.”

*The name of the person giving the testimony was changed to keep it confidential and avoid judicial revenge

Por Luz Mendoza, Eju.tv:

Proceso abreviado: Inocentes obligados a aceptar la culpa para detener la depredación judicial

Acontece frecuentemente que por las “miserias evidentes” del sistema penal de Bolivia, luego de una serie de intentos infructuosos del acusado para demostrar su inocencia —que no está obligado a hacerlo—, ante la indolencia del sistema y usualmente estando detenido, no le queda otra que declararse culpable para intentar lograr algún beneficio.

Foto ilustrativa: FP

La Paz, 8 de abril de 2024 (ANF).- —No importa si eres inocente, aquí hay un muerto y no podemos liberarte —fue la respuesta del juez presidente del tribunal a Felipe, que, al verse sin una moneda en el bolsillo, acudió a él, desesperado, para dar término a un proceso judicial que en una década le había quitado años, fuerza y vida.

Estaba endeudado y sin trabajo. Le llamaba su abogado, quería dinero, dinero, y más dinero “a pesar de que no hacía nada o muy poco”. Fue al cajero y no había nada, ni para el pasaje. Hace días comía muy poco, lo que había. La preocupación le consumía. Asistir a las audiencias en cualquier momento era un martirio que azotaba su tranquilidad.

—Yo soy inocente y lo puedo demostrar, pero ya no tengo dinero, y ya estoy harto, ya no tengo ni ganas de leer los tomos del expediente —le encaró al juez.

Felipe dice que después de tantos años agarrar lo mismos textos judiciales, que tuvo en las manos reiteradas veces para leer y releer, resulta tedioso, “ya no te dan ganas”, además de la posibilidad de que todo sea en vano.

Estudió derecho estando preso. Como alumno ávido de conocimiento pasó días y noches enteras repasando y entendiendo los códigos, confiando en que la ley era garantía de orden y justicia para defender su inocencia. La presión fue tan fuerte que se ganó una embolia. Todo en vano. El desengaño fue brutal.

—Mejor es que te vayas al abreviado o te vamos a dar 30 años, no importa si eres inocente, porque aquí hay un muerto, no podemos liberarte, ya pasó tanto tiempo, porque si no mi cabeza también está en juego pues ¬—le respondió el juez presidente.

Felipe dice que si salía inocente los fiscales y jueces iban a tener que pagarle por todo el daño que cometieron con él al mantenerlo preso tantos años. Pensaba iniciarles un juicio, pero ahora, con el ánimo y la salud disminuida, era más difícil.

Endeudado y sin trabajo ¿Qué prefería? ¿Seguir pagando a un abogado o darle de comer a su familia o a sí mismo? Tuvo que escoger. Tuvo que elegir. Dice que lo económico fue un factor muy importante para que haya optado por el proceso abreviado.

Con mucho dolor, después de tantos años de lucha para salir del proceso y ser liberado, de ver a su familia cuánto había luchado por él, “fue duro ver que toda la lucha había sido en vano”.

—Fue muy triste para mi decir, porque te hacen leer, ‘usted se hace responsable de este hecho’, y decir sí sin haberlo hecho, creo que fue uno de los momentos más difíciles que tuve en la vida, y también para mi familia, todos estaban llorando, después de tanto luchar al final tuve que agachar la cabeza para someterme a este sistema corrupto.

Felipe fue acusado por la muerte de un joven en 2014, sin haber estado en el lugar y con pruebas científicas que concluían que el ADN encontrado en las uñas de la víctima, que se defendió, no era de él, sino de una tercera persona no identificada. En 2017 fue sentenciado a 30 años de cárcel sin derecho a indulto en el penal de San Pedro, pero tres años después el proceso fue a foja cero por graves aberraciones judiciales. Se ordenó un nuevo proceso.

Arturo Yañez Cortez, reconocido jurista, escribió en su columna “Procedimiento abreviado, ¿igual a culpabilidad?”, que esa admisión de culpabilidad por la que el acusado se pone la “soga en el cuello aceptando una inmediata condena” no siempre en la realidad significa que sea culpable, en razón a que operan muchos factores que pueden conducir a que, al acusado, aún inocente, a la vista del desastre del proceso penal, no le quede otra que declararse culpable.

Dijo que entre ellos acontece frecuentemente que por las “miserias evidentes” del sistema penal boliviano, luego de una serie de intentos infructuosos del acusado para demostrar su inocencia —que no está obligado a hacerlo—, ante la indolencia del sistema y usualmente estando detenido, no le queda otra que declararse culpable para intentar lograr algún beneficio. “Un proceso penal, peor si es con detención, embargo de bienes, gastos, separación y frecuentemente abandono de la familia, escarnio social, etc., destruye casi irremediablemente el proyecto de vida de cualquier ser humano”.

—Deme menos años si me acojo al abreviado, para ya no volver a la cárcel—le dijo Felipe al juez presidente.

Felipe llevaba 10 años de proceso judicial, de los cuales seis había estado en la cárcel. Sumido en la pobreza, y con su proyecto de vida destruido, veía el procedimiento abreviado como única opción para poner fin a tanto padecimiento. Pero el padecimiento no llegaba a su fin. El juez presidente quería capitalizar hasta el último aliento de un alma moribunda y desesperada.

El juez presidente le propuso 20 años, pero “si tienes 5.000 dólares bajamos los años para que se acabe todo, de una vez”, recuerda Felipe que le dijo el funcionario.

La pesadilla del dinero volvía a presentarse, el juez presidente “era como un mercader que busca sacar provecho de todo, hasta de los pellejos, no pensé que en el abreviado también pedían dinero”.

—Si tuviera ese dinero seguiría en el juicio, pero eso es lo que no tengo —le respondió.

—Trata de conseguir, somos entre tres, no solo es mi cabeza —le retrucó el juez haciéndole entender que se trata de un grupo, como una mafia, que tras un golpe debe repartir el dinero entre todos.

Al juez presidente no le importaba si encarcelaba a un inocente o si liberaba a un asesino, solo quería dinero o que se acabe su fatigada realidad de revisar montañas de expedientes en un sistema judicial atosigado por miles de casos.

—Además, ya me da flojera llevar todo esto otra vez, tengo tantos casos y otra vez leer tu expediente, para nosotros va ser un alivio si te vas al abreviado y ahí se acabó con nosotros —dijo el juez y mantuvo la propuesta de 20 años de cárcel con la esperanza de que Felipe acepte pagar algo.

—Pero voy a tener que volver a la cárcel si me das 20 años.

—Claro, pero solo van a ser unos años y vas a salir con plata, adentro sé que salen con más plata, yo sé cómo es allá adentro.

Jueces como el juez presidente hacen de la justicia un producto a la carta, donde las sentencias, sin importar la gravedad, tienen precio, como se develó con el caso del feminicida Richard Choque que pagó en 2015 al juez de ejecución penal Rafael Alcón Aliaga 3.500 dólares y una botella de whisky para que, mediante una artimaña jurídica, saliera libere.

—Usted piensa que soy un delincuente, seguro que para un delincuente que está acostumbrado a eso está bien, pero mi anhelo de vida no es ese, no es estar en la cárcel y delinquir —le cuestionó. Al ver que efectivamente no podría conseguir nada de Felipe, el juez presidente lo condenó a 15 años de cárcel.

El artículo 373 del Código de Procedimiento Penal, señala que una vez “Concluida la investigación, el fiscal encargado podrá solicitar al juez de la instrucción, en su requerimiento conclusivo, que se aplique el procedimiento abreviado”.

Y, para que sea procedente, “deberá contar con el acuerdo del imputado (sin ninguna presión) y su defensor, el que deberá estar fundado en la admisión del hecho y su participación en él”, es decir, admitir la responsabilidad del delito.

Felipe recuerda que el sistema de justicia siempre le sugirió el proceso abreviado, desde su aprehensión, sin haber investigado nada. Policías, funcionarios penitenciarios, abogados, fiscales, en todo momento sacaban el tema.

—En mi caso vinieron el fiscal y unos abogados indicándome que me vaya al abreviado, desde el momento en que me habían detenido. Yo decía por qué voy a ir al abreviado, por qué me voy a echar la culpa de algo que no he cometido, pero todo el mundo te dice que te vayas al abreviado, hasta los policías, y mucha gente cae en eso.

Hacinamiento

El procedimiento abreviado es usado para bajar los niveles de hacinamiento de las cárceles, ahorrar recursos y hasta intentar mostrar rápidos y efectivos “resultados”. Felipe dice que es para que las autoridades “se laven las manos” y puedan “liberarse de cualquier duda sobre su idoneidad”, por eso “para ellos es simple pedirlo”, porque “no te ven como a una persona, sino como un número”. De acuerdo al informe de Rendición Pública de Cuentas Final del Tribunal Supremo de Justicia, en 2023, luego de audiencias en siete recintos carcelarios, 134 privados de libertad se acogieron al procedimiento abreviado. Felipe refiere que, en su caso, después de tantos años, tuvo que hacer lo mismo.

—Todo esto es un gasto económico terrible y en lo personal ha sido totalmente destructivo para mi economía, para mi forma de vida, inclusive.

Tantos años de trajinar en el camino sinuoso del sistema judicial ha cambiado su perspectiva. Al principio creía que el juez era una persona idónea, superior, muy bien formada, sabia —por algo se les dice señoría—, pero conocer de cerca el sistema le ha brindado un conocimiento más cabal. Dice que están llenos de prejuicios, se guían por las apariencias y no respetan ni la ley que dicen aplicar y defender. Arranca a carcajadas cuando escucha decir a los funcionarios del Ministerio Público que la Fiscalía es una de las instituciones con “mayor prestigio”.

—Ellos hablan mucho de la ética, pero ya te juzgan por tu color de piel, por tu religión, por tus gustos musicales o por cómo te vistes; suponen mucho, dicen: él es (culpable), se nota, has visto sus ojos, su mirada, cosas así de ridículas para nuestro entender, no son nada profesionales.

En la primera sentencia, los jueces técnicos que lo condenaron no tomaron en cuenta la prueba de ADN que lo liberaba de culpa, pero sí su doctrina de músico de rock anticristiana y concluyeron que “desprecia la vida” y por lo tanto es culpable.

Felipe está convencido de que la justicia es un negocio, lo conoce desde adentro, y a cualquier persona con un problema legal que le pregunta qué puedo hacer, le responde: Si tienes plata, págale al fiscal o al juez y ahí se acabó.

—Uno cree que el abogado le va a ayudar, que lo que dice es la verdad, pero al final te das cuenta que no es así, que todo es un negocio —refiere y recuerda que su primer abogado prometió sacarlo en seis meses, pero tomó sus únicos cuatro mil dólares y desapareció.

La justicia le ha enseñado que entre contratar un abogado que domina el procedimiento y otro que es chicanero, es preferible optar por el que hace chicanas, él te va a sacar, porque con el otro “vas a estar años caminando y al final vas a llegar a lo mismo que el chicanero te va a decir”.

—Yo ya no creo en la capacidad un abogado, más bien creo en cuán virtuoso es hacer charlas o cosas fuera de la ley, porque querer dinero es parte común de ellos, de los fiscales y jueces.

La única tranquilidad que le da haberse acogido al proceso abreviado es que ya no irá a audiencias ni pensará en buscar dinero para dárselo al abogado y pagar trámites en el sistema corrupto. Pero un peso social y moral inmenso lo acompañará por siempre. Nadie conoce sus motivaciones para optar por el abreviado, solo él y su familia.

—Todas las personas que ahora leen o se enteran de que me fui al abreviado dicen: ‘había sido verdad, por eso se ha ido al abreviado, él había sido’, eso piensa la mayoría de la gente que me conoce, no dicen que yo no tenía dinero y me vi obligado, la persona común y silvestre no conoce bien ese veneno que es el sistema judicial.

Su moral quedó totalmente afectada. Una persona con principios y valores, con una vida tranquila, una profesión y un proyecto, al aceptar haber cometido algo tan terrible, después de “hacer hasta lo imposible por demostrar mi inocencia”, siente una pérdida incuantificable.

—Pensé ilusamente que el Código de Procedimiento Penal servía, pero no sirve. Y ahora pienso por qué tuvo que pasar por todo esto, por qué toda esta pena, inclusive económica, a veces no tengo ni qué comer, por qué tuve que pasar tantas cosas y de paso aceptar una culpa, decir ‘yo soy el culpable’.

*El nombre de la persona que da el testimonio fue cambiado para mantenerlo en reserva y evitar la venganza judicial