William Herrera, El Deber:

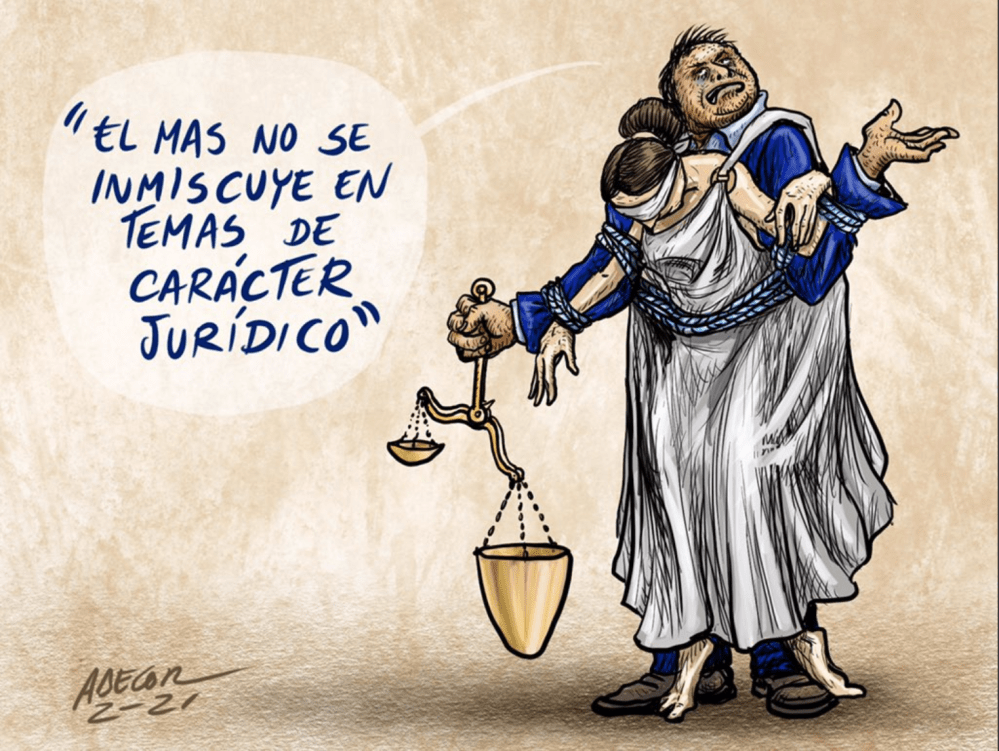

Far from changing and improving the Judiciary, it remains in free fall. That the legislators have not carried out the preselection and election of the new authorities of the High Courts means entering not only into an unprecedented and dangerous judicial vacuum, but also constitutes a true failure for the national government, the MAS and the political forces.

The Constitution establishes that the main judicial authorities will be elected by universal suffrage, and the Plurinational Legislative Assembly must carry out “by two thirds of its members present the preselection of the applicants for each department and will send to the Electoral Body the list of those prequalified for that it proceeds to the sole and exclusive organization of the electoral process” (arts. 182.II-198). And since this entire procedure has been aborted, any decision that attempts to “get out of trouble” (short law, interim terms, extension of mandate, etc.) will be unconstitutional (and can be sued and aborted again). This pandemonium can generate conflicts of all kinds and unforeseeable consequences.

Legislators want a law that allows substitute magistrates to be appointed to replace the heads of the Judicial Branch as of January 2024, when the six-year constitutional mandate of the highest authorities of the Supreme Court of Justice (TSJ) the Constitutional Court, Plurinational (TCP), the Agro-environmental Court and the Judicial Council ends. Another proposal is that the Constitution Commission of the Legislative Assembly draws lots among the departmental members and appoints the magistrates and on January 2 the new authorities are installed for a maximum period of six months or sooner, a period in which they would have the pending electoral process must be carried out. What seems to be a political consensus is that the current judicial authorities, who complete their mandate on January 2, 2024, do not stay another minute in their positions.

What is very clear is that there is no political will to allow judicial renewal in the terms established by the Constitution, much less to seek a transformation of Bolivian justice. Meanwhile the snowball continues. Judicial coverage is not only limited and deficient, but non-existent for more than 50% of the national territory. Judicial coverage reaches 48% of the country’s 339 municipalities, the public ministry reaches 41% and the public defense service reaches 29% of the municipalities, according to the Construir Foundation.

The judicial budget barely reaches 0.50% of the general budget of the State. The Government and Defense ministries have (and have had) more than 40% of the total. The poor judicial budget allocation constitutes a determining element for the systematic degradation not only of the justice system, but also of the political system, constitutional rights and values. Under these conditions, it is an impossible mission for judges to have the minimum conditions in terms of infrastructure, institutional strengthening, a complete judicial career, cutting-edge technology, decent remuneration, etc. The situation is truly critical since work is increasing exponentially, but the conditions do not exist to resolve the high procedural burden and the great challenges required by the transformation of the judicial function.

The aforementioned indicators confirm that “justice” is not and has not been a priority for the Bolivian political class. The IDH Commission recommended that the Bolivian State “adopt the necessary measures to achieve the greatest possible coverage of judges, prosecutors and public defenders, based on criteria resulting from diagnoses of the real needs of the different areas of the country, both in population and in matters”, measures that “must include budgetary and human support so that in addition to the physical presence of the respective authority, its permanence and the stability of its personnel are guaranteed.”

International standards not only require that there be economic independence of justice, but also that the budget project be prepared by the Judiciary itself; They even raise the need to enshrine constitutional clauses to safeguard a minimum budget for the justice system. The truth is that the MAS model of justice has failed and they must take charge of the monster they have created and its consequences.

Lejos de cambiar y mejorar el Poder Judicial sigue en caída libre. Que los legisladores no hayan realizado la preselección y elección de las nuevas autoridades de las Altas Cortes, supone ingresar no solo en un inédito y peligroso vacío judicial, sino también constituye un verdadero fracaso para el gobierno nacional, el MAS y las fuerzas políticas.

La Constitución establece que las principales autoridades judiciales se elegirán mediante sufragio universal, debiendo la Asamblea Legislativa Plurinacional efectuar “por dos tercios de sus miembros presentes la preselección de las postulantes y los postulantes por cada departamento y remitirá al Órgano Electoral la nómina de los precalificados para que éste proceda a la organización, única y exclusiva, del proceso electoral” (arts. 182.II-198). Y como todo este procedimiento ha sido abortado, cualquier decisión que intente “salir del paso” (ley corta, interinatos, prórroga de mandato, etc.) será inconstitucional (y puede ser demandada y abortada nuevamente). Este pandemónium puede generar conflictos de todo tipo y de imprevisibles consecuencias.

Los legisladores quieren una ley que permita designar a los magistrados suplentes en reemplazo de los titulares del Órgano Judicial a partir de enero del 2024, cuando fenezca el mandato constitucional de seis años de las máximas autoridades del Tribunal Supremo de Justicia (TSJ) el Tribunal Constitucional Plurinacional (TCP), el Tribunal Agroambiental y el Consejo de la Magistratura. Otra propuesta es que la Comisión de Constitución de la Asamblea Legislativa haga un sorteo entre los vocales departamentales y designe a los magistrados y el 2 de enero se posesione a las nuevas autoridades por un plazo máximo de seis meses o antes, lapso en el cual tendría que realizarse el proceso eleccionario pendiente. En lo que pareciera haber consenso político es que las actuales autoridades judiciales, que cumplen su mandato el 2 de enero de 2024, no se queden un minuto más en sus cargos.

Lo que está clarísimo es que no hay voluntad política, que permita la renovación judicial en los términos que establece la Constitución, menos para buscar una transformación de la justicia boliviana. Mientras tanto sigue la bola de nieve. La cobertura judicial no sólo que es limitada y deficiente sino inexistente para más del 50% del territorio nacional. La cobertura judicial llega al 48% de los 339 municipios del país, el ministerio público llega al 41% y el servicio de defensa pública llega al 29% de los municipios, según la Fundación Construir.

El presupuesto judicial apenas alcanza al 0,50% del presupuesto general del Estado. Los ministerios de Gobierno y de Defensa tienen (y han tenido) más del 40% del total. La pobre asignación presupuestaria judicial constituye un elemento determinante para la sistemática degradación no solo del sistema de justicia, sino también del sistema político, los derechos y valores constitucionales. En estas condiciones, resulta misión imposible que los jueces tengan las condiciones mínimas en lo que hace a infraestructura, fortalecimiento institucional, una carrera judicial completa, tecnología de punta, remuneraciones dignas, etc. La situación es realmente crítica ya que aumenta exponencialmente el trabajo, pero no existen las condiciones para resolver la elevada carga procesal y los grandes desafíos que exige la transformación de la función judicial.

Los referidos indicadores confirman que la “justicia” no es ni ha sido una prioridad para la clase política boliviana. La Comisión IDH recomendó al Estado boliviano que “adopte las medidas necesarias para lograr la mayor cobertura posible de jueces, fiscales y defensores públicos, a partir de criterios que resulten de diagnósticos sobre las reales necesidades de las distintas zonas del país, tanto en población como en materias”, medidas que “deben incluir el apoyo presupuestario y humano para que además de la presencia física de la autoridad respectiva, se garantice su permanencia y la estabilidad de su personal”.

Los estándares internacionales no sólo exigen que haya independencia económica de la justicia, sino además de que el proyecto de presupuesto sea preparado por el propio Poder Judicial; incluso, plantean la necesidad de consagrar cláusulas constitucionales de salvaguarda de un mínimo presupuestario para el sistema de justicia. Lo cierto es que el modelo de justicia del MAS ha fracasado y deben hacerse cargo del monstruo que han creado y de sus consecuencias.

https://eldeber.com.bo/edicion-impresa/vacio-judicial_349142

We want an independent and impartial Justice!!