Editorial, LosTiempos:

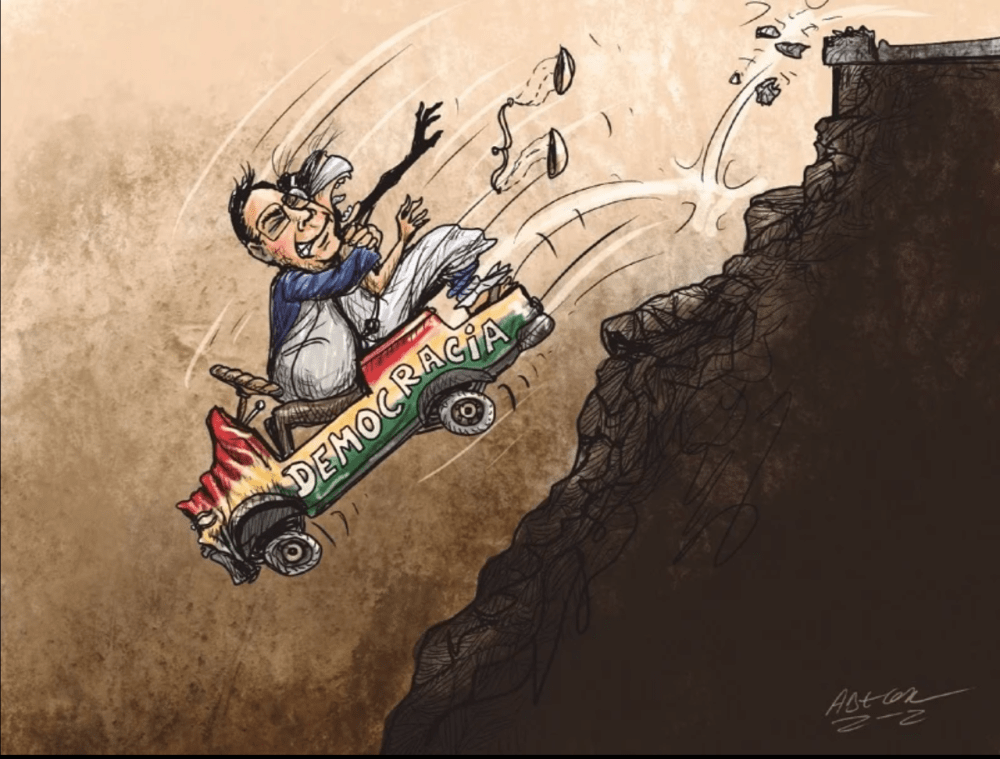

On December 31 at midnight —as established by the Political Constitution of the State (CPE)—, the highest authorities of the Judicial Branch end their mandate and must be replaced, at the beginning of January 2024, by others elected in elections that are impossible to hold on time.

In these circumstances—as a former constitutional magistrate warns—“there will be no control of legality or constitutionality,” since there is no constitutional way to overcome it. And the continuity, beyond December 31, of the current magistrates in their functions will weaken legal security, since their decisions will be null.

How will the acephaly be resolved in the Supreme Court of Justice, the Plurinational Constitutional Court, and the Agro-Environmental Court, in addition to the Judicial Council?

Who benefits from this situation? These are two of the three inevitable questions that are difficult to answer. The third: how did this situation come about? reveals a paradox: the essential legislative process for holding the elections began eight months ago in March and was paralyzed twice by the Plurinational Constitutional Court (TCP), the first for three months and four days, the second lasting 70 days.

The Plurinational Legislative Assembly began the process the first week of March and on the 27th of that month approved the regulations and call for the preselection of applicants qualified to participate in those elections that were to be held next Sunday.

Three weeks later, the process had its first judicial setback: a constitutional chamber of Beni annulled that regulation.

On April 20, the ALP approved a new call and a new regulation, and a week later the TCP froze the entire process as a result of the admission of an abstract unconstitutionality appeal presented by an opposition deputy.

Anticipating that the TCP would delay its ruling, the Executive presented a bill to modify the deadlines that the ALP approved and the president promulgated on June 5.

Meanwhile, the TCP continued preparing the sentence that it would issue three months and four days after having paralyzed the process.

At the beginning of September, the Senate approved a bill for these elections and a commission of Deputies sent it for consultation to the Electoral Body, the Ministry of Justice, the Supreme Court of Justice (TSJ) and the Council of the Judiciary.

And on September 20, the TSJ presented a constitutionality control query to the TCP, which once again paralyzed the process for the judicial elections, it is not known for how long.

El 31 de diciembre a medianoche —como lo establece la Constitución Política del Estado (CPE)—, las máximas autoridades del Órgano Judicial terminan su mandato y deben ser reemplazadas, al inicio de enero de 2024, por otras electas en unos comicios imposibles de realizarse a tiempo.

En esas circunstancias —como advierte un exmagistrado constitucional—, “no habrá control de legalidad ni de constitucionalidad”, pues no existe una vía constitucional para superarla. Y la continuidad, más allá de 31 de diciembre, de los actuales magistrados en sus funciones fragilizará la seguridad jurídica, pues sus decisiones serán nulas.

¿Cómo se resolverá la acefalía en los tribunales Supremo de Justicia, Constitucional Plurinacional, y Agroambiental, además del Consejo de la Magistratura?

¿A quién beneficia esta situación? Son dos de las tres preguntas inevitables y de difícil respuesta. La tercera: ¿cómo se llegó a esta situación? revela una paradoja: el imprescindible proceso legislativo para la realización de las elecciones se inició hace ocho meses en marzo y fue paralizado dos veces por el Tribunal Constitucional Plurinacional (TCP), la primera, durante tres meses y cuatro días, la segunda dura ya 70 días.

La Asamblea Legislativa Plurinacional comenzó el trámite la primera semana de marzo y el 27 de ese mes aprobó el reglamento y convocatoria para la preselección de postulantes habilitados para participar de esas elecciones que debían realizarse el próximo domingo.

Tres semanas después, el proceso tuvo su primer tropiezo judicial: una sala constitucional del Beni anulaba esa normativa.

El 20 de abril la ALP aprobó una nueva convocatoria y un nuevo reglamento, y una semana más tarde el TCP congelaba todo el proceso como efecto de la admisión de un recurso de inconstitucionalidad abstracta presentado por un diputado opositor.

Previendo que el TCP demoraría en su fallo, el Ejecutivo presentó un proyecto de ley para modificar los plazos que la ALP aprobó y el presidente promulgó el 5 de junio.

Mientras, el TCP continuaba preparando la sentencia que emitiría tres meses y cuatro días después de haber paralizado el proceso.

A principios de septiembre el Senado aprobó un proyecto de ley para esas elecciones y una comisión de Diputados lo envió en consulta al Órgano Electoral, al Ministerio de Justicia, al Tribunal Supremo de Justicia (TSJ) y al Consejo de la Magistratura.

Y el 20 de septiembre el TSJ presentó al TCP una consulta de control de constitucionalidad, lo que paralizó nuevamente el proceso para las elecciones judiciales, no se sabe hasta cuándo.

https://www.lostiempos.com/actualidad/opinion/20231129/editorial/elecciones-judiciales