By Eju.tv

The adjustment and its political bill: the cost Rodrigo Paz faces after the fuel hike

The increase in fuel prices and the easing of diesel controls open a front of social and economic pressure for the government. Analysts warn of inflationary impact and political wear, while the transport sector distances itself and demands compensation.

eju.tv / Video: Social Networks

The economic measures announced on Tuesday night by President Rodrigo Paz—including the increase in fuel prices and the rise of the national minimum wage to Bs 3,300—have sparked a public debate among different sectors in recent hours. Some support the measures as necessary, while others warn about their impact on the economy of the most vulnerable sectors and on inflationary pressure.

Economists, former authorities, and social sectors have begun to warn that the adjustment, although defended as necessary by the Executive, will carry a high and difficult-to-manage political cost. From an economic standpoint, analyst Gonzalo Chávez pointed out that fuel price increases have a transversal effect on the economy, particularly on transportation, the logistics chain, and final food prices.

In his analysis, the economist warned that any fuel adjustment ends up being passed on to consumers, generates inflationary pressure, and deteriorates purchasing power, especially among urban and popular sectors. Chávez also stressed that without a clear compensation plan, the government is exposed to rapid erosion of credibility—one of the factors that threatens to undermine the 65% popularity it currently enjoys, according to a recent survey broadcast on a national television network.

A similar view was expressed by former Minister of Hydrocarbons Álvaro Ríos, who argued that the measure reflects accumulated fiscal tensions and the difficulty of sustaining the subsidy scheme in the current economic context. Ríos warned that beyond the technical rationale of the adjustment, the central problem is political, as the Executive assumes the cost of an unpopular decision in a fragile social scenario with little room for public tolerance.

The Minister of Economy and Public Finance. Photo: Unitel

According to the former minister, the risk is that the fuel price increase becomes a trigger for social conflict if it is not accompanied by clear signals of state austerity and social dialogue. “We could not continue subsidizing hydrocarbons for the entire country while on top of that 20% or 25% goes across our borders. It’s tough, but it’s what has to be done,” he said, adding that while the wage increase and bonuses will act as a ‘cushion,’ the next step should be a new Hydrocarbons Law to attract investment.

The political impact began to be felt more strongly in the transport sector, the most sensitive to diesel and gasoline prices. Leaders of urban, interprovincial, and heavy transport federations expressed their rejection of the increase and warned that operating costs will rise immediately; therefore, they made it clear that they will evaluate fare adjustments and do not rule out mobilizations if the government does not propose compensation mechanisms or price controls.

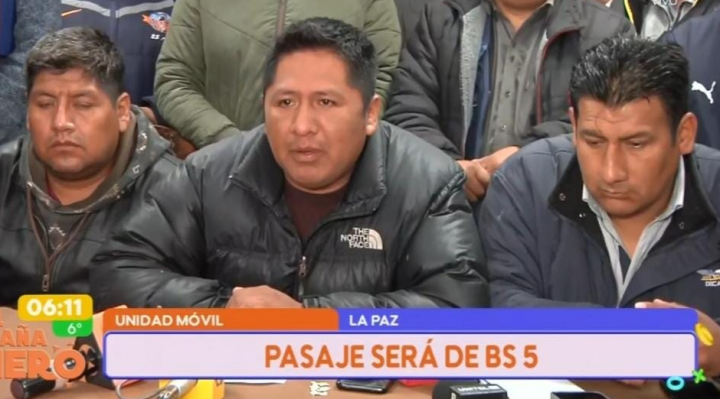

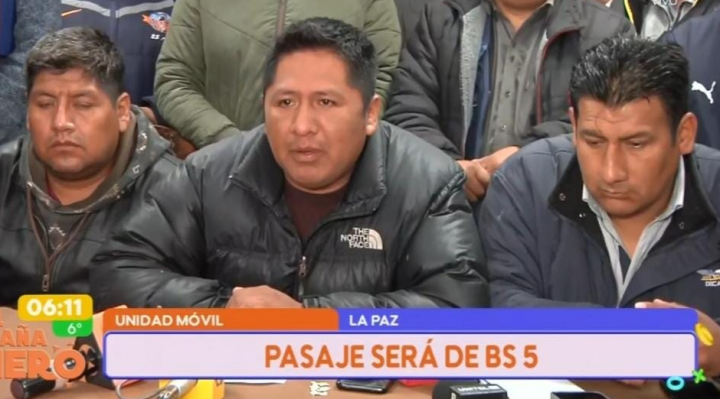

“It has been a heavy blow to the popular sectors,” said Limberth Tancara, leader of the Free Transport Union of La Paz, referring to the elimination of fuel subsidies. “We have issued instructions for all our minibus operators that, from this moment, the fare within the municipality of La Paz is Bs 5. The trufi on long routes is Bs 6.50,” he said. The measure will be replicated by other transport unions across the country.

La Paz drivers announce fare increases. Photo: screenshot Red Uno

La Paz drivers announce fare increases. Photo: screenshot Red Uno

However, Economy Minister José Gabriel Espinoza said the government has taken measures to reduce transport operators’ operating costs, including the elimination of tariffs and levies on the import of tires, lubricants, and spare parts. In his view, the cost structure of passenger transport is not limited solely to fuel. “The government is absolutely open to dialogue; we will set up dialogue tables with different sectors,” he said, although he warned that it will not allow transport operators to take advantage of the situation to raise fares unjustifiably.

On the political front, opposition figures agreed that the announcement directly hits the image of President Rodrigo Paz, who had maintained a discourse of economic stability and protection of household budgets. For several analysts, the Executive now faces the challenge of explaining why the adjustment is inevitable and how to prevent its effects from falling disproportionately on the most vulnerable sectors.

Hydrocarbons expert Francesco Zaratti said that the Rodrigo Paz government had no alternative but to assume the partial elimination of subsidies; however, he estimated that the government must “flood” the domestic market with diesel to show that the measure works. He noted that the fiscal deficit was “unsustainable,” especially when combined with the lack of international reserves and dollars to purchase imported fuels (90% of diesel and 55% of gasoline). “Maintaining supply was becoming increasingly onerous,” he said.

Samuel Doria Medina, leader of the Unidad alliance, defended the removal of hydrocarbon subsidies and said it was a necessary measure to confront the disaster left by the government of the Movement for Socialism (MAS), comparable to cancer. “They left us such a terrible economic disaster that it is comparable to cancer; therefore, the solution also has to be radical and equivalent to chemotherapy. I have undergone chemotherapy; it is complex, but it ensures that after some time you return to normal life. That is what has been done with these measures,” he said.

Former Senate president and former minister Óscar Ortiz said the decisions taken by the government are necessary and that fuel subsidies were “unsustainable.” “Here we are all going to have to make sacrifices. If prices are not raised, we won’t be able to supply ourselves. Today we do not have the necessary dollars to guarantee gasoline and diesel subsidies,” Ortiz said. “The new measures adopted by the government were necessary. The announcements are positive; however, the heart of the measures is fuel prices,” he added.

For his part, the president of the Santa Cruz Chamber of Industry, Commerce, Services, and Tourism (Cainco), Jean Pierre Antelo, questioned the increase in the national minimum wage set by the government for 2026 as part of the anti-crisis package. “The announced minimum wage, however, repeats schemes that have already shown their limits, as it did not arise from tripartite dialogue among workers, the private sector, and the State,” he said in a post on his X account.

The debate is no longer focused solely on the economic viability of the measures, but on their political sustainability. The fuel price increase places the government before a colossal challenge: it must show that the measures were taken to contain the deficit and bring order to public finances; otherwise, it will face an escalation of social pressure that could erode its political capital. The outcome will depend largely on the Executive’s ability to demonstrate that the adjustment will not, once again, be paid for by the citizenry.

Por Eju.tv:

El ajuste y su factura política: el costo que enfrenta Rodrigo Paz tras el alza de carburantes

El incremento en el precio de los combustibles y la flexibilización del control al diésel abren un frente de presión social y económica para el Gobierno. Analistas advierten impacto inflacionario y desgaste político, mientras el transporte marca distancia y exige compensaciones.

eju.tv / Video: RRSS

Las medidas económicas anunciadas la noche del martes por el presidente Rodrigo Paz, entre ellas el incremento en el precio de los carburantes y del salario mínimo nacional a Bs 3.300 activaron en las últimas horas un debate público entre diferentes sectores, unos que apoyan la medida porque la estiman necesaria y otros que alertan sobre el impacto que tendrá en la economía de los sectores más vulnerables y en la presión inflacionaria.

Economistas, exautoridades y sectores sociales comenzaron a advertir que el ajuste, aunque defendido como necesario por el Ejecutivo, tendrá un costo político alto y difícil de administrar. Desde el ámbito económico, el analista Gonzalo Chávez señaló que el aumento de los combustibles tiene un efecto transversal en la economía, particularmente en el transporte, la cadena logística y los precios finales de los alimentos.

En su análisis, el economista advirtió que cualquier ajuste en los carburantes termina trasladándose al consumidor, genera presión inflacionaria y deteriora el poder adquisitivo, especialmente en los sectores urbanos y populares. Chávez remarcó además que, sin un plan claro de compensaciones, el Gobierno queda expuesto a un rápido desgaste de credibilidad. Uno de los elementos que amenaza con socavar la popularidad del 65% que ostenta, según una reciente encuesta difundida en una red televisiva nacional.

Una lectura similar planteó el exministro de Hidrocarburos Álvaro Ríos, quien sostuvo que la medida refleja las tensiones fiscales acumuladas y la dificultad de sostener el esquema de subvenciones en el actual contexto económico. Ríos advirtió que, más allá de la racionalidad técnica del ajuste, el problema central es político ya que el Ejecutivo asume el costo de una decisión impopular en un escenario social frágil y con escaso margen de tolerancia ciudadana.

El ministro de Economía y Finanzas Públicas. Foto: Unitel

Según el exministro, el riesgo es que el incremento de los carburantes se convierta en un detonante de conflictividad si no se acompaña de señales claras de austeridad estatal y diálogo social. “No podíamos seguir subsidiando los hidrocarburos para todo el país y encima que un 20% o 25% se vaya por nuestras fronteras. Es duro, es lo que hay que hacer”, afirmó, para luego puntualizar que si bien el incremento salarial y los bonos actuarán como un ‘colchón’, el siguiente paso debe ser una nueva Ley de Hidrocarburos que atraiga inversión.

El impacto político comenzó a sentirse con mayor fuerza en el sector del transporte, el más sensible al precio del diésel y la gasolina. Dirigentes de federaciones de transporte urbano, interprovincial y pesado expresaron su rechazo al alza y advirtieron que los costos operativos se incrementarán de manera inmediata; por ello, dejaron claro que evaluarán ajustes en las tarifas y no descartan movilizaciones si el Gobierno no plantea mecanismos de compensación o control de precios.

“Ha sido un golpe fuerte a los sectores populares”, afirmó el dirigente del Transporte Libre de La Paz, Limberth Tancara, en referencia a la eliminación de la subvención de los combustibles. “Hemos sacado la instrucción para toda nuestra modalidad de minibuses que el pasaje a partir de este momento es de Bs 5 dentro del municipio de La Paz. El trufi en el tramo largo es de Bs 6,50”, afirmó. La medida será replicada por otras dirigencias del resto del país.

Los choferes de La Paz anuncian el incremento de los pasajes. Foto: captura de pantalla Red Uno

Los choferes de La Paz anuncian el incremento de los pasajes. Foto: captura de pantalla Red Uno

Sin embargo, el ministro de Economía, José Gabriel Espinoza, señaló que el Gobierno ha tomado medidas para reducir los costos de operación de los transportistas, entre ellas la eliminación de aranceles y gravámenes para la importación de llantas, lubricantes y repuestos. En su criterio, la estructura de costos del transporte de pasajeros no solo se limita al combustible. “El gobierno está absolutamente abierto al diálogo, vamos a presentar mesas de diálogo con distintos sectores”, dijo, aunque advirtió que no permitirá que los transportistas se aprovechen de la situación para subir las tarifas de manera injustificada.

En el plano político, opositores coincidieron en que el anuncio golpea directamente la imagen del presidente Rodrigo Paz, quien había sostenido un discurso de estabilidad económica y protección al bolsillo ciudadano. Para varios analistas, el Ejecutivo enfrenta ahora el desafío de explicar por qué el ajuste es inevitable y cómo evitar que sus efectos recaigan de forma desproporcionada en los sectores más vulnerables.

El experto en hidrocarburos Francesco Zaratti señaló que el gobierno de Rodrigo Paz no tenía otra alternativa que asumir la eliminación parcial de la subvención; pero, estimó que el Gobierno tiene que ‘inundar’ de diésel el mercado interno para mostrar que su medida funciona. Manifestó que el déficit fiscal ‘era insostenible’, más si se suma la falta de reservas internacionales y de dólares para comprar los combustibles importados (un 90% de diésel y un 55% de gasolina). “Mantener el suministro era cada vez más oneroso”, dijo.

Samuel Doria Medina, líder de la alianza Unidad, defendió el retiro de la subvención de los hidrocarburos y afirmó que fue una medida necesaria, para enfrentar el desastre que dejó el gobierno del Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS), comparable a un cáncer. “Nos han dejado un desastre tan terrible en la economía que es comparable a un cáncer, por eso la solución tiene que ser, también, radical y equivalente a una quimioterapia. La quimioterapia, yo la he sufrido, es compleja, pero te asegura que, después de un tiempo vuelva a la vida normal. Eso se ha hecho con estas medidas”, afirmó.

El expresidente del Senado y exministro, Óscar Ortiz, señaló que las decisiones asumidas por el Gobierno son necesarias y que la subvención a los combustibles era ‘insostenible’. “Aquí vamos a tener que sacrificarnos todos. Si no se sube el precio, no vamos a poder abastecernos. Hoy no tenemos los dólares necesarios para garantizar la subvención de la gasolina y el diésel”, afirmó Ortiz. “Eran necesarias las nuevas medidas que ha adoptado el Gobierno. Los anuncios son positivos; sin embargo, el corazón de las medidas es el precio de los combustibles”, sostuvo.

Por su parte, el presidente de la Cámara de Industria, Comercio, Servicios y Turismo de Santa Cruz (Cainco), Jean Pierre Antelo, cuestionó el incremento al salario mínimo nacional, dispuesto por el Gobierno para 2026 contemplado en el paquete de medidas contra crisis. “El salario mínimo anunciado, sin embargo, repite esquemas que ya mostraron límites, al no surgir de un diálogo tripartito entre trabajadores, sector privado y Estado”, señaló el directivo en una publicación en su cuenta de X.

El debate ya no se centra únicamente en la viabilidad económica de las medidas, sino en su sostenibilidad política. El aumento de los carburantes coloca al Gobierno ante un reto descomunal, porque debe mostrar que tomó las medidas para contener el déficit y ordenar las finanzas públicas; caso contrario, enfrentará una escalada de presión social que puede erosionar su capital político. El resultado dependerá, en gran medida, de la capacidad del Ejecutivo para demostrar que el ajuste no será, una vez más, pagado por la ciudadanía.