By Mauricio Goio Eju.tv:

Jesuit missions and the imagination of a different order

In the South American rainforest, a different kind of city was attempted: plazas, workshops, and baroque choirs coexisted with forest rituals. These reductions showed that, even under colonial violence, it was possible to imagine another order — imperfect, yet profoundly human.

In times of mistrust and confrontation, history teaches us that it is possible to promote projects even in extreme circumstances. Despite language barriers and the conflicts inherent to any society, human beings have sought understanding and worked for the common good. Not always in ideal conditions, but with the will to overcome differences to achieve shared goals.

Throughout history there have been initiatives that, despite difficulties and disagreements, managed to unite people from diverse origins around common objectives. These cases demonstrate that even when a path is marked by conflict, the pursuit of dialogue and cooperation can prevail and benefit society as a whole.

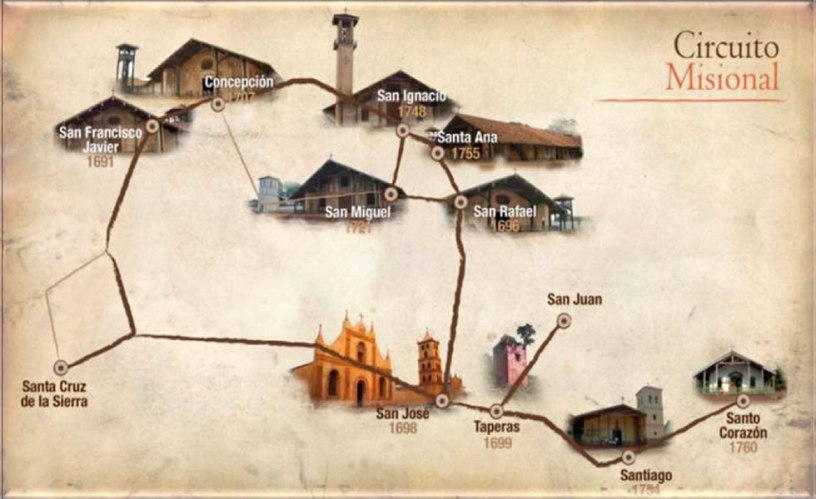

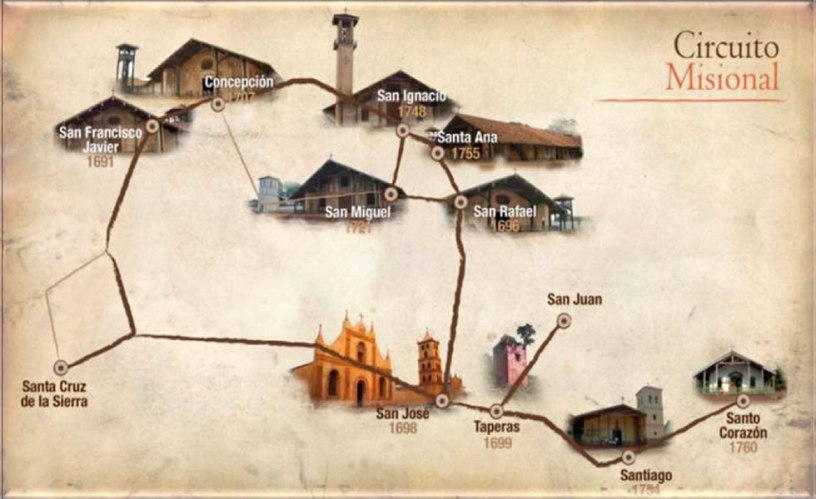

This is how, on the margins of the Spanish Empire during the 17th century, a social and cultural experiment emerged that challenged traditional colonial logics: the Jesuit missions. In the vast South American forest, Jesuits and Indigenous peoples collaborated to create settlements that blended Indigenous language, European architecture, communal economies, and hybrid rituals. Far from being a mere episode of evangelization, this process constituted a — fragile, tense, and luminous — attempt to live together amid colonial violence and dispossession.

By the mid-17th century, the South American frontier was a territory of blurry boundaries and constant threats. Imperial expansion advanced through encomienda, cross, and sword, imposing models of domination and exploitation. Against this backdrop, the Jesuits proposed an alternative: the construction of reductions. Towns organized under communal and spiritual principles, where faith, work, music, and discipline were integrated into a new form of social architecture.

Yet the true movement took place on the cultural and symbolic plane. Coexistence between Jesuits and Indigenous peoples was not linear nor free of tension. The latter accepted, adorned, resisted, and transformed the teachings that arrived from Europe, generating a constant dynamic of negotiation.

One of the most innovative aspects of the missions was the priority the Jesuits gave to learning the local language. Before building temples, they dedicated themselves to understanding the local idiom and worldview. Evangelization thus became an exercise in impossible translation, where catechisms and ancestral myths intertwined in a gentle battle of meanings. Missionaries had to adapt concepts, give ground on metaphors, and invent equivalences to convey the Christian message. Meanwhile, Indigenous peoples reinterpreted Christ as a hero moving between worlds, appropriating ritual without abandoning the memory of the forest.

This cultural syncretism manifested itself in religious celebrations that combined Indigenous drums and baroque choirs, and in images carved with the aesthetics of the forest, with profoundly American eyes. Jesuit flexibility — criticized by Dominicans and Franciscans who accused the Society of Jesus of tolerating “pagan” practices — was key to the rise of a mestizo religiosity that survived even after the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767.

The Jesuit reductions were laid out as school-cities, with a central plaza from which straight streets extended, a church that marked the rhythm of daily life, and carpentry and blacksmith workshops. Gardens allowed for up to four annual harvests, and community life was organized around music, work, and education. The cabildo functioned as a hybrid political space where the cacique coexisted with Spanish officials and collective decisions were negotiated.

The Indigenous militia, far from being a military imposition, served as defense against the Portuguese bandeirantes, who threatened to capture and enslave the inhabitants of the missions. The communal economy, based on collective labor and redistribution, aroused suspicion among colonial merchants, who viewed the reductions as an inconvenient competitor. Agricultural and livestock success fueled the myth of “Jesuit wealth,” later used in Bourbon politics to justify the expulsion of the Society.

As with any human experience, the missions had their darker side. Life was regulated by bells, schedules, and ecclesiastical authorities, and there were internal conflicts and attempts to flee. External criticism and tensions with the Spanish monarchy reflected the complexity of a project that was never homogeneous nor free of contradictions.

More interesting, however, are the anonymous testimonies and local voices. Letters written in Guaraní by 18th-century Indigenous people, city models that still impress with their precision, Christmas carols blending Spanish, Latin, and the voices of the forest, and documents recording constant negotiation between caciques and priests to prevent escapes, punishments, or breakdowns in coexistence, reveal the agency and creativity of Indigenous communities.

The Jesuit missions constituted a multiple frontier: political, religious, economic, and above all symbolic. They were neither Europe nor America, neither Indigenous purity nor colonial domination. They were a territory where two imaginaries attempted to live together, confronting the contradictions and tensions that mark every human project.

Perhaps this is why they remain so fascinating. Because they show that even on the edges of an empire and amid violence and dispossession, there were those who imagined a more balanced world, where work was not slavery, music held as much weight as the sword, and a Guaraní child could learn to read without being torn from his community. The missions were not a perfect utopia, but they were a reminder that Latin American history is not made only of oppression, but also of — imperfect and fragile — attempts at coexistence and creativity.

The experience of the Jesuit missions invites us to rethink Latin American history from a more complex and nuanced perspective. Beyond royal decrees and Enlightenment debates, the essential lies in everyday testimonies, in the capacity for dialogue, and in the creativity of those who, amid adversity, imagined a different order. The legacy of the missions is, above all, an invitation to recognize the diversity of experiences and the possibility of building spaces of coexistence and mestizaje even in the most difficult contexts.

Por Mauricio Jaime Goio Eju.tv:

Las misiones jesuíticas y la imaginación de un orden distinto

En la selva sudamericana se ensayó una ciudad distinta: plazas, talleres y coros barrocos convivían con rituales del monte. Aquellas reducciones mostraron que, aun bajo la violencia colonial, se podía imaginar otro orden —imperfecto, pero profundamente humano.

En tiempos de desconfianza y enfrentamiento, la historia nos enseña que es posible impulsar proyectos incluso en circunstancias extremas. A pesar de las barreras idiomáticas y los conflictos propios de cualquier sociedad, los seres humanos han sabido buscar el entendimiento y trabajar por el bien común. No siempre en un ambiente ideal, pero sí con la voluntad de superar las diferencias para lograr objetivos compartidos.

A lo largo de la historia han existido iniciativas que, pese a las dificultades y los desacuerdos, lograron unir a personas de distintos orígenes en torno a metas comunes. Estos casos demuestran que, aunque el camino esté marcado por el conflicto, la búsqueda del diálogo y la cooperación puede prevalecer y beneficiar a toda la sociedad.

Así fue como en los márgenes del imperio español, durante el siglo XVII, surgió un experimento social y cultural que desafió las lógicas coloniales tradicionales: las misiones jesuíticas. En la vasta selva sudamericana, jesuitas y aborígenes colaboraron en la creación de pueblos que mezclaban lengua indígena, arquitectura europea, economía comunal y rituales híbridos. Este proceso, lejos de ser un simple episodio de evangelización, constituyó un intento —frágil, tenso y luminoso— de habitar juntos en medio de la violencia y la desposesión colonial.

A mediados del siglo XVII, la frontera sudamericana era un territorio de límites difusos y constantes amenazas. La expansión imperial avanzaba a golpe de encomienda, cruz y espada, imponiendo modelos de dominación y explotación. Frente a este escenario, los jesuitas propusieron una alternativa: la construcción de reducciones. Pueblos organizados bajo principios comunitarios y espirituales, donde la fe, el trabajo, la música y la disciplina se integraban en una arquitectura social novedosa.

Sin embargo, el verdadero movimiento ocurría en el plano cultural y simbólico. La convivencia entre jesuitas y aborígenes no fue un proceso lineal ni exento de tensiones. Los últimos aceptaron, decoraron, resistieron y transformaron las enseñanzas que les llegaban desde Europa, generando una dinámica de negociación constante.

Uno de los aspectos más innovadores de las misiones fue la prioridad que los jesuitas dieron al aprendizaje de la lengua local. Antes de levantar templos, se dedicaron a comprender el idioma y la cosmovisión local. La evangelización se convirtió así en un ejercicio de traducción imposible, donde catecismos y mitos ancestrales se entrelazaban en una batalla suave de significados. Los misioneros tuvieron que adaptar conceptos, ceder en metáforas e inventar equivalencias para transmitir el mensaje cristiano. Por su parte, los nativos resignificaron a Cristo como un héroe que desciende y asciende entre mundos, apropiándose del ritual sin abandonar la memoria del bosque.

Este sincretismo cultural se manifestó en las celebraciones religiosas, que mezclaban tambores indígenas y coros barrocos, y en las imágenes talladas con estética del monte, de ojos profunamente americanos. La flexibilidad jesuítica, criticada por dominicos y franciscanos que acusaban a la Compañía de Jesús de tolerar prácticas “paganas”, fue clave para el surgimiento de una religiosidad mestiza que sobrevivió incluso a la expulsión de los jesuitas en 1767.

Las reducciones jesuíticas se dispusieron como ciudades-escuela, con una plaza central desde la cual irradiaban calles rectas, una iglesia que marcaba el ritmo de la vida diaria y talleres de carpintería y herrería. Los huertos permitían hasta cuatro cosechas anuales, y la vida comunitaria se organizaba en torno a la música, el trabajo y la educación. El cabildo funcionaba como un espacio político híbrido, donde el cacique convivía con figuras españolas y se negociaban decisiones colectivas.

La milicia indígena, lejos de ser una imposición militar, servía como defensa frente a los bandeirantes portugueses, que amenazaban con capturar y esclavizar a los habitantes de las misiones. La economía comunal, basada en el trabajo colectivo y la redistribución, generó suspicacias entre los comerciantes coloniales, que veían en las reducciones un competidor incómodo. El éxito agrícola y ganadero alimentó el mito de la “riqueza jesuítica”, que terminó siendo utilizada en la política borbónica para justificar la expulsión de la Compañía.

Como toda experiencia humana, las misiones tuvieron su parte oscura. La vida estaba regulada por campanas, horarios y autoridades eclesiásticas, y no faltaron conflictos internos ni intentos de fuga. Las críticas externas y las tensiones con la monarquía española reflejan la complejidad de un proyecto que nunca fue homogéneo ni exento de contradicciones.

Lo más interesante, sin embargo, ocurre en los testimonios anónimos y en las voces locales. Las cartas escritas en guaraní por aborígenes del siglo XVIII, las maquetas de ciudades que aún sorprenden por su precisión, los villancicos que mezclan castellano, latín y voces de la selva, y los documentos que registran la negociación constante entre caciques y padres para evitar fugas, castigos o quiebras en la convivencia, revelan la agencia y creatividad de los pueblos originarios.

Las misiones jesuíticas constituyeron una frontera múltiple: política, religiosa, económica y, sobre todo, simbólica. No eran Europa, ni América, ni pureza indígena ni dominio colonial. Eran un territorio donde dos imaginarios ensayaron una manera de vivir juntos, enfrentando contradicciones y tensiones propias de todo proyecto humano.

Quizás por eso siguen fascinando. Porque muestran que, incluso en los márgenes de un imperio y en medio de la violencia y la desposesión, hubo quienes imaginaron un mundo más equilibrado, donde el trabajo no era esclavitud, la música tenía el mismo peso que la espada, y un niño guaraní podía aprender a leer sin ser arrancado de su comunidad. Las misiones no fueron una utopía perfecta, pero sí un recordatorio de que la historia de América Latina no está hecha solo de opresión, sino también de intentos —imperfectos y frágiles— de convivencia y creatividad.

La experiencia de las misiones jesuíticas invita a repensar la historia latinoamericana desde una perspectiva más compleja y matizada. Más allá de los decretos reales y las polémicas ilustradas, lo esencial se encuentra en los testimonios cotidianos, en la capacidad de diálogo y en la creatividad de quienes, en medio de la adversidad, imaginaron un orden distinto. El legado de las misiones es, ante todo, una invitación a reconocer la diversidad de experiencias y la posibilidad de construir espacios de convivencia y mestizaje, incluso en los contextos más difíciles.

https://eju.tv/2025/11/las-misiones-jesuiticas-y-la-imaginacion-de-un-orden-distinto/