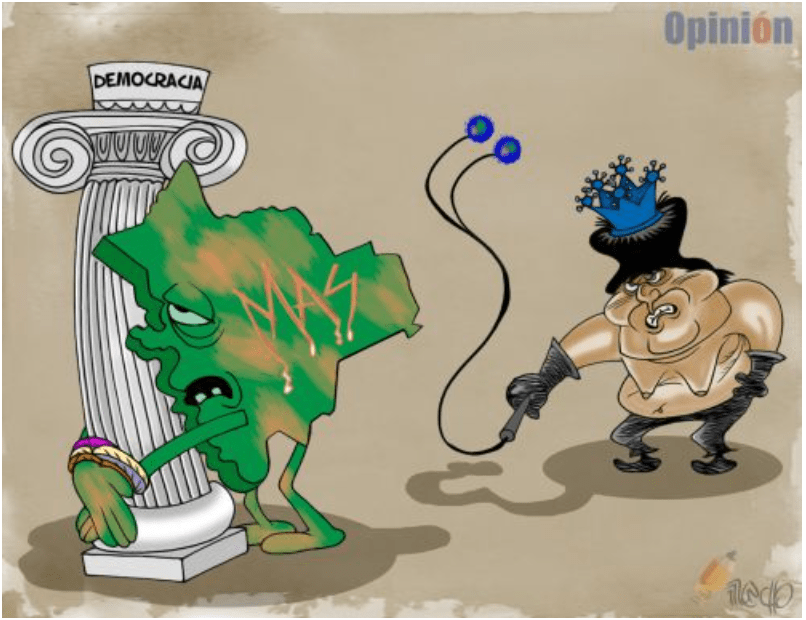

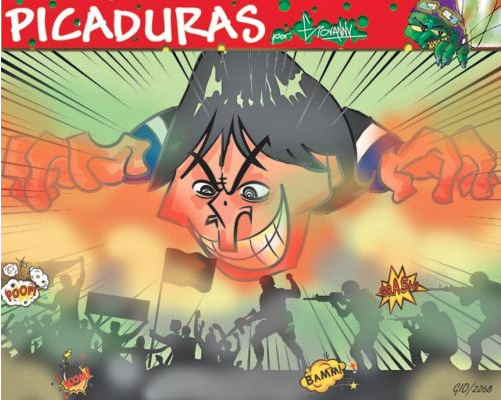

Lupe Cajias, Los Tiempos:

The Trumpeter Who Returned to Dust

The biography of Evo Morales Ayma (Orinoca-Oruro Canton, 1959) is recounted in the most mythological ways. Iván Canelas, one of his biographers and former minister, claimed that Evo followed the path of Jesus; in the manger of Plaza Murillo, they placed a big-headed baby as Morales. No one knows how much was spent for Martín Sivac to follow him for three years to write the praises in “Jefazo.” Argentinians assert that an elderly teacher in Salta remembered that “bolita” who was already showing signs of leadership in first grade.

Dozens of press articles around the world repeat stories that were never verified. Perhaps the only ones who could clarify some scenes from his early biographical videos are Iván Iporre, “Evo’s eyes and arms” from before he became president, or Alex Contreras, another of his biographers and his spokesperson until 2008. The little peasant boy running after oranges seems more like a scene from Isico in the movie “Chuquiago” than a real anecdote. The story that he was a good soccer player and that’s why he was invited to be a leader seems more like an imitation of Juan Lechín’s beginnings; Morales needs to kick his opponent to win, as we have seen. He got angry when CNN’s team defeated the players he had on his planes. How much did he pay and with what budget did he transport his team?

Morales himself liked to tell events in one way and then in another; for example, the passage of his father bribing the rural teacher so that his son could pass the grade. In his 18 years of government, in addition to his decades as a union leader, he recounted scenes that have no other source to be verified.

However, the hard data of this man’s trajectory are enough to astonish. Born in a typical poor farmer’s home in one of the most remote highlands from any city, he suffered alongside his family from forced economic exiles. He was a migrant in northern Argentina. After the drought that devastated the highlands in the 1980s, he went to the tropics in Cochabamba. There, he became an Andean man wearing short-sleeved shirts.

It is very possible that he worked as a baker, bricklayer, ice cream vendor. There is a photo showing him fulfilling his military service with the faces of many rural youth who proudly wear the uniform that consecrates their citizenship.

The people of Oruro were happy to have a fellow citizen when he arrived at the Government Palace and stepped out onto the balcony on behalf of so many marginalized Bolivians. Combative like his ancestors, they were also the first to halt his narcissistic ambition. Evo, at the height of his power, wanted to change the name of the airport dedicated to the great Juan Mendoza and put his image as he did in the Cable Car, in subsidized food, on the roads. The Oruro Civic Committee did not allow it.

In Oruro, they claim he played the trumpet in one of the big bands. In 2006, the audience at the famous carnival’s entrance welcomed him with applause and cheers. He seemed to parade in his element (very different from other politicians who become Transformer dancers). At another carnival, alongside foreign footballers who enjoyed his generous friendship, he encountered the “familiar face” that was part of his downfall.

In the 2024 carnival, the former trumpeter was declared persona non grata for instigating blockades that affected tourism in Oruro, the city’s most secure source of income. The sumptuous museum adorned for him by the publicist Juan Carlos Valdivia, director of a short film about Evo the footballer, is now dusty. If before only a few visited, now no one comes.

The trumpeter doesn’t even have the chance to attend as a former president in an official box. He is obliged to sit like any other spectator, incognito. Evo Morales cannot bear that anonymity. He cannot walk peacefully in airports or Plaza Murillo or attend union congresses. He is confined to a radio booth.

He, who was awarded honorary doctorates by various universities, is now persona non grata in neighboring countries and cannot vacation wherever he pleases. Isolated, he cannot even hire private planes from his friends who now refuse to gift him more horses.

Evo was a coca grower leader dedicated to his grassroots until 1994; he faced the empire that ravaged the producers. He was loved, admired. Power and advisors from Havana, Caracas, São Paulo, and Puebla twisted his fate. He personally dealt the treacherous blow to each of his comrades from difficult times. The worst was the poisoned dagger to end Filemón Escóbar.

The traitor now feels betrayed.

Solitary, his old signs of paranoia worsen. He hallucinates visions where he is seen alongside Simón Bolívar or next to Víctor Paz. His face, his gesture, his expression say more than his words.

He is no longer a trumpeter; he can no longer dance at the entrance of the Oruro carnival.

Even worse, synthetic drugs are displacing cocaine. Coca prices are falling worldwide; traffickers and consumers are onto something else. Even the sacred leaf has abandoned him.

El trompetista que volvió al polvo

La biografía de Evo Morales Ayma (cantón Orinoca-Oruro, 1959) es contada de las formas más mitológicas. Iván Canelas, uno de sus biógrafos y exministro, aseguró que Evo seguía el camino de Jesús; en el pesebre de la plaza Murillo colocaron un niñito cabezón como Morales. Nadie sabe cuánto se gastó para que Martín Sivac lo siga durante tres años para escribir las loas en “Jefazo”. Los argentinos aseguran que una viejecita profesora de Salta se acordaba de ese “bolita” que ya daba muestras de liderazgo en primero de primaria.

Decenas de artículos de prensa en todo el mundo repiten historias que nadie comprobó. Quizá los únicos que podrían aclarar algunas escenas de sus primeros videos biográficos son Iván Iporre, “los ojos y los brazos del Evo” desde antes de que sea presidente, o Alex Contreras otro de sus biógrafos y su vocero hasta 2008. El campesinito corriendo detrás de unas naranjas parece más una escena de Isico en la película Chuquiago que una anécdota real. Ese cuento de que era buen jugador de fútbol y por eso lo invitaron a ser dirigente parece más una imitación a los inicios de Juan Lechín; Morales necesita patear al contrincante para ganar, así lo vimos. Se enojó cuando el equipo de CNN venció a los jugadores que llevaba en sus aviones. ¿Cuánto pagaba y con qué presupuesto trasladaba su equipo?

El propio Morales gustaba contar hechos de una forma y luego de otra; por ejemplo, el pasaje de su padre sobornando al maestro rural para que su hijo pase de curso. En los 18 años de gobierno, además de sus décadas de dirigente sindical, relató estampas que no tienen otra fuente para ser verificadas.

Sin embargo, los datos duros de la trayectoria de este hombre son suficientes para asombrar. Nacido en un típico hogar de agricultores pobres en uno de los páramos más alejados de cualquier ciudad, sufrió junto a su familia los forzados exilios económicos. Fue migrante en el norte argentino. Después de la sequía que asoló al altiplano en los 80, partió al trópico en Cochabamba. Ahí se convirtió en un andino que usaba camisa con mangas cortas.

Es muy posible que haya trabajado como panadero, ladrillero, heladero. Hay una foto que lo muestra cumpliendo su servicio militar con el rostro de muchos jóvenes rurales que lucen orgullosos el uniforme que consagra su ciudadanía.

Los orureños estaban felices por tener un paisano cuando él llegó al Palacio de Gobierno y salió al balcón en representación de tantos bolivianos postergados. Combativos como sus antepasados, fueron también los primeros en detener su ambición narcisista. Evo, en el momento de mayor poder, quería cambiar el nombre del aeropuerto dedicado al gran Juan Mendoza y poner su imagen como hizo en el Teleférico, en los alimentos del subsidio, en las carreteras. El Comité Cívico orureño no se lo permitió.

En Oruro aseguran que tocaba la trompeta en una de las grandes bandas. En 2006, el público de la Entrada del famoso carnaval lo recibió con aplausos y vítores. Él parecía desfilar en su salsa (muy diferente a otros políticos que se convierten en bailarines Transformers). En otro carnaval, junto a futbolistas extranjeros que gozaron de su generosa amistad, se encontró con la “cara conocida “que fue parte de su perdición.

En el carnaval de 2024, el antiguo trompetista fue declarado persona non grata por instar a bloqueos que afectaron al turismo en Oruro, la fuente más segura de ingresos para esa ciudad. El suntuoso museo que le adornó el publicista Juan Carlos Valdivia, realizador de un cortometraje sobre Evo futbolista, está empolvado. Si antes lo visitaban unos cuantos, ahora no llega nadie.

El trompetista no tiene ni siquiera la chance de asistir como expresidente a un palco oficial. Está obligado a sentarse como un espectador más, de incógnito. Evo Morales no soporta ese anonimato. No puede caminar tranquilo en los aeropuertos o por la plaza Murillo ni asistir a congresos sindicales. Está recluido en una cabina de radio.

Él, que fue declarado doctor honoris causa por distintas universidades, ahora es persona non grata en países vecinos y no puede pasar vacaciones donde le guste. Aislado, no puede ni contratar avionetas privadas de sus amigos que ahora se niegan a regalarle otros caballos.

Evo fue un dirigente cocalero dedicado a sus bases hasta 1994; enfrentó al imperio que asolaba a los productores. Era querido, admirado. El poder y los consejeros de La Habana, de Caracas, de Sao Paulo y de Puebla torcieron su destino. Él personalmente clavó la puñalada trapera en las espaldas de cada uno de sus camaradas de las épocas difíciles. La peor fue la daga envenenada para acabar con Filemón Escóbar.

El traicionero se siente ahora traicionado.

Solitario, empeoran sus antiguos signos de paranoia. Cree visiones donde se ve junto a Simón Bolívar o al lado de Víctor Paz. Su rostro, su gesto, su expresión dicen más que sus palabras.

Ya no es trompetista; ya no puede bailar en la entrada del carnaval de Oruro.

Peor aún, las drogas sintéticas están desplazando a la cocaína. Los precios de la coca caen en el mundo; los traficantes y los consumidores están en otra. Hasta la hoja sagrada lo ha abandonado.

https://www.lostiempos.com/actualidad/opinion/20240329/columna/trompetista-que-volvio-al-polvo