By Maggy Talavera:

#analysis by Gonzalo Chávez Álvarez on the measures launched by the government:

Fuel prices increase in Bolivia. First reaction.

As anticipated, the economy has entered a phase of abrupt correction of relative prices, marked by the withdrawal of one of the historical pillars of the economic model: the generalized subsidy to hydrocarbons.

The so-called “price adjustment” has been forceful. Gasoline recorded an increase of 86.1%, rising from 3.74 to 6.96 bolivianos per liter, while diesel—the most critical energy input for the productive structure—nearly tripled in price, climbing from 3.72 to 11 bolivianos, equivalent to an increase of 195.7%.

This asymmetry is not trivial: diesel is the fuel for heavy transport, agro-industry, and logistics, so its increase anticipates a cascade effect on production costs and, ultimately, on the prices of food and basic goods.

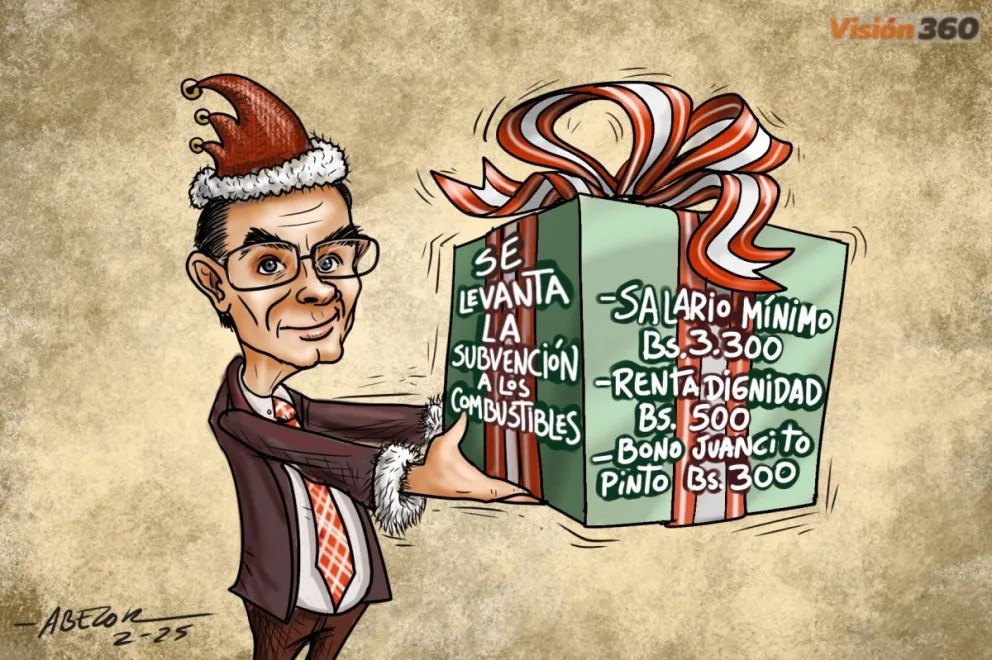

In response to this shock, the government has deployed a scheme of social compensations that operates selectively. On the one hand, a 20% increase in the minimum wage was decreed, consistent with projected inflation for 2025. On the other, the policy of direct transfers was reinforced with significantly larger increases: the Renta Dignidad rose by 66.7% (from 300 to 500 bolivianos) and the Juancito Pinto bonus by 50% (from 200 to 300 bolivianos).

The message is clear: the State seeks to protect non-working sectors—older adults and students—with greater intensity, while trusting that the wage adjustment will sustain the purchasing power of the employed population.

However, a closer analysis reveals several structural tensions. First, compensations are heavily concentrated in the formal sector of the economy, both through the minimum wage and through state-administered bonuses. This design overlooks a key fact of economic reality: nearly 80% of the economically active population is in the informal sector, without a guaranteed minimum wage, without contracts, and in many cases without direct access to the announced compensation mechanisms. For this segment, the diesel shock translates into higher transport and input costs, but without an equivalent safety net.

Second, the increase in the minimum wage, while aiming to preserve the real income of formal workers, introduces additional pressure on private companies, many of which already operate in a context of recession, falling sales, and financial constraints. In this sense, wage policy functions as a mechanism of social compensation, but also as a source of tension for formal employment, especially in small and medium-sized enterprises with narrow margins.

Added to these weaknesses is a significant political dimension. The adjustment has been implemented without a broad political agreement in the Legislative Assembly, support that would have been desirable to provide the measure with greater legitimacy and sustainability.

The absence of broad consensus increases the risk of reversal, blockades, or social conflict, especially in a context where the fuel price increase had long been announced and, therefore, anticipated by organized groups.

Likewise, the compensation scheme shows evident gaps. Clear mechanisms have not been defined for key sectors such as public transport, whose cost structure depends almost exclusively on diesel. The major unanswered question is what will happen to urban, interprovincial, and interdepartmental transport fares. An adjustment in these prices could amplify the inflationary impact on households, while a freeze would shift losses to transport operators already affected by rising costs.

Finally, the adjustment raises a deeper debate about its scope and equity. It is inevitable to ask why tougher measures were not simultaneously adopted on the public spending side, such as closing loss-making state-owned enterprises, significant cuts to public-sector payrolls, or a more aggressive rationalization of the state apparatus. By not addressing these fronts, the adjustment falls disproportionately on prices and the real income of households, rather than distributing costs between the public and private sectors.

In sum, the country faces a classic fiscal adjustment: distorted prices are corrected to relieve public finances, but considerable inflationary pressure is transferred to the real economy. The outcome will depend on three key factors: whether the 20% wage increase manages to sustain consumption in a context of skyrocketing energy costs; whether broader and more inclusive compensation mechanisms are designed, especially for the informal sector and transport; and, finally, the reaction of organized groups to a shock that, although announced, remains socially and politically explosive.

Added to this picture is an additional macroeconomic risk that cannot be underestimated: the high probability of accelerating inflation. The diesel shock—due to its cross-cutting effect on transport, food, and logistics—can quickly turn into persistent inflation if informal indexation mechanisms, unanchored expectations, and preventive price adjustments are activated. To prevent this process from evolving into an inflationary spiral that is difficult to control, the government would be practically compelled to adopt a strongly contractionary monetary policy, based on a significant increase in interest rates and credit restriction.

However, this medicine has severe side effects. Higher rates raise the cost of financing for firms and households, cool investment, and reduce consumption, deepening an already recessionary scenario. In other words, the classic dilemma reappears starkly: contain inflation at the cost of deeper recession, or tolerate further deterioration of purchasing power to avoid a collapse in economic activity. In an economy with high informality, limited access to credit, and financially fragile firms, the contractionary channel of monetary policy tends to be particularly regressive and ineffective at disciplining prices, while strongly punishing employment and production.

Thus, the current adjustment not only faces the social challenge of compensating an unprecedented price shock, but also the technical challenge of coordinating fiscal, social, and monetary policy in a context of fragile expectations. If inflation accelerates and the monetary response is excessively restrictive, the country could become trapped in a particularly costly combination: high inflation with deep recession, a scenario that typically erodes the political legitimacy of the adjustment rapidly and reactivates social conflict. The balance between stabilization and economic sustainability will therefore be the true test of this stage of the correction program.

Por Maggy Talavera:

#análisis de Gonzalo CHavez Alvarez sobre las medidas lanzadas por el gobierno:

Se incrementan los precios de los combustibles en Bolivia. Primera reacción.

Tal como se preveía, la economía ha ingresado en una fase de corrección abrupta de precios relativos, marcada por el retiro de uno de los pilares históricos del modelo económico: la subvención generalizada a los hidrocarburos.

El llamado “sinceramiento” de precios ha sido contundente. La gasolina registró un incremento del 86,1%, pasando de 3,74 a 6,96 bolivianos por litro, mientras que el diésel, el insumo energético más crítico para la estructura productiva, prácticamente triplicó su precio al subir de 3,72 a 11 bolivianos, lo que equivale a un aumento del 195,7%.

Esta asimetría no es trivial: el diésel es el combustible del transporte pesado, la agroindustria y la logística, por lo que su encarecimiento anticipa un efecto cascada sobre los costos de producción y, en última instancia, sobre el precio de los alimentos y bienes básicos.

Frente a este shock, el gobierno ha desplegado un esquema de compensaciones sociales que opera de manera selectiva. Por un lado, se decretó un incremento del salario mínimo del 20%, coherente con la inflación proyectada para 2025. Por otro, se reforzó la política de transferencias directas con aumentos significativamente mayores: la Renta Dignidad subió un 66,7% (de 300 a 500 bolivianos) y el bono Juancito Pinto un 50% (de 200 a 300 bolivianos).

El mensaje es claro: el Estado intenta proteger con mayor intensidad a los sectores no laborales, adultos mayores y estudiantes, mientras confía en que el ajuste salarial sostenga el poder adquisitivo de la población ocupada.

Sin embargo, un análisis más fino revela varias tensiones estructurales. En primer lugar, las compensaciones están fuertemente concentradas en el sector formal de la economía, tanto a través del salario mínimo como de los bonos administrados por el Estado. Este diseño deja al margen a un dato clave de la realidad económica: cerca del 80% de la población económicamente activa se encuentra en el sector informal, sin salario mínimo garantizado, sin contratos y, en muchos casos, sin acceso directo a los mecanismos de compensación anunciados. Para este segmento, el shock del diésel se traduce en mayores costos de transporte y de insumos, pero sin una red de protección equivalente.

En segundo lugar, el aumento del salario mínimo, si bien busca preservar el ingreso real de los trabajadores formales, introduce una presión adicional sobre las empresas privadas, muchas de las cuales ya operan en un contexto de recesión, caída de ventas y restricciones financieras. En este sentido, la política salarial funciona como un mecanismo de compensación social, pero también como un factor de tensión para el empleo formal, especialmente en pequeñas y medianas empresas con márgenes estrechos.

A estas debilidades se suma una dimensión política no menor. El ajuste se ha implementado sin un acuerdo político amplio en la Asamblea Legislativa, respaldo que habría sido deseable para dotar a la medida de mayor legitimidad y sostenibilidad.

La ausencia de consensos amplios aumenta el riesgo de reversión, bloqueos o conflictividad social, especialmente en un contexto donde el aumento de los combustibles era largamente anunciado y, por tanto, anticipado por la población organizada.

Asimismo, el esquema de compensación muestra vacíos evidentes. No se han definido mecanismos claros para sectores clave como el transporte público, cuya estructura de costos depende casi exclusivamente del diésel. La gran pregunta pendiente es qué ocurrirá con las tarifas del transporte urbano, interprovincial e interdepartamental. Un ajuste en estos precios podría amplificar el impacto inflacionario sobre los hogares, mientras que su congelamiento trasladaría las pérdidas a transportistas ya afectados por el alza de costos.

Finalmente, el ajuste plantea un debate más profundo sobre su alcance y equidad. Resulta inevitable preguntar por qué no se optó simultáneamente por medidas más duras del lado del gasto público, como el cierre de empresas estatales deficitarias, recortes significativos en planillas salariales del sector público o una racionalización más agresiva del aparato estatal. Al no abordar estos frentes, el ajuste recae de manera desproporcionada sobre los precios y el ingreso real de los hogares, en lugar de distribuir los costos entre el sector público y privado.

En suma, el país enfrenta un ajuste fiscal clásico: se corrigen precios distorsionados para aliviar las finanzas públicas, pero se traslada una presión inflacionaria considerable a la economía real. El desenlace dependerá de tres factores clave: si el aumento salarial del 20% logra sostener el consumo en un contexto de costos energéticos disparados; si se diseñan mecanismos de compensación más amplios e inclusivos, especialmente para el sector informal y el transporte; y, finalmente, de la reacción de la población organizada frente a un shock que, aunque anunciado, sigue siendo social y políticamente explosivo.

A este cuadro se suma un riesgo macroeconómico adicional que no puede subestimarse: la probabilidad elevada de una aceleración inflacionaria. El shock del diésel —por su efecto transversal sobre transporte, alimentos y logística— puede transformarse rápidamente en inflación persistente si se activan mecanismos de indexación informal, expectativas desancladas y ajustes preventivos de precios. Para evitar que este proceso derive en una espiral inflacionaria difícil de controlar, el gobierno se vería prácticamente obligado a adoptar una política monetaria fuertemente contractiva, basada en un aumento significativo de las tasas de interés y en la restricción del crédito.

Sin embargo, esta medicina tiene efectos colaterales severos. Un alza de tasas encarece el financiamiento para empresas y hogares, enfría la inversión y reduce el consumo, profundizando un escenario ya recesivo. En otras palabras, el dilema clásico reaparece con crudeza: contener la inflación a costa de más recesión, o tolerar un mayor deterioro del poder adquisitivo para evitar un colapso de la actividad económica. En una economía con alta informalidad, bajo acceso al crédito y empresas financieramente frágiles, el canal contractivo de la política monetaria tiende a ser especialmente regresivo y poco eficaz para disciplinar precios, mientras castiga con fuerza al empleo y a la producción.

Así, el ajuste actual no solo enfrenta el desafío social de compensar un shock de precios sin precedentes, sino también el reto técnico de coordinar política fiscal, social y monetaria en un contexto de expectativas frágiles. Si la inflación se acelera y la respuesta monetaria es excesivamente restrictiva, el país podría quedar atrapado en una combinación particularmente costosa: inflación alta con recesión profunda, un escenario que suele erosionar rápidamente la legitimidad política del ajuste y reactivar la conflictividad social. El equilibrio entre estabilización y sostenibilidad económica será, por tanto, el verdadero examen de esta etapa del programa de corrección.