By Juan José Toro, Correo del Sur:

Cave paintings found in southern Bolivia reveal human settlements dating back approximately 10,000 years

As Bolivia draws ever closer to the bicentennial of its independence, it has become increasingly clear that several cultures flourished in this territory long before the arrival of the so-called Inca Empire.

In Chuquisaca, the most studied culture is the Yampara, but others also existed in the rest of the department—such as the Charcas—leaving behind traces of their existence that are now under archaeological study. Potosí fared better in this regard: thanks to colonial documents like the Memorial de Charcas and testimonies from dozens of laypeople, we now know that at least eight distinct cultures thrived in that department: Qaraqara, Karanka, Killaka, Lípez, Sura, Chicha, Chui, and the aforementioned Charcas.

While the existence of these cultures is accepted, what is their origin? It is important to note here that the most widely accepted theory on the origin of humans in the Americas is the migrationist theory. That is, it proposes that the Americas were populated by waves of migrants who arrived from Asia, Africa, or Europe, either during the time of the supercontinent Pangaea or by crossing ice-covered waters at what is now the Bering Strait.

WORLD HERITAGE

These migratory waves entered our continent via Beringia, the land bridge that formed between western Alaska and eastern Siberia during the glacial period in what is now the Bering Strait. Initially settling in the north, they gradually moved throughout the lands that today make up the Americas. It is estimated that around 40,000 years ago, humans entered present-day North America. While some groups settled and established colonies, others continued southward through Central America, eventually reaching South America—a process that spanned thousands of years.

Around 20,000 years ago, they arrived at what is now the Chiribiquete mountain range, a group of rocky plateaus located not only in the Colombian Amazon but also reaching into Brazil.

The Chiribiquete range lies in Colombia’s Caquetá and Guaviare departments, straddling the equator—literally the center of the world. There, anthropologist Carlos Castaño Uribe found cave paintings estimated to be 22,000 years old, confirming that major migratory waves reached the area during that time.

The importance of the find is such that Chiribiquete has been inscribed on UNESCO’s list of natural and cultural heritage sites.

IN POTOSÍ

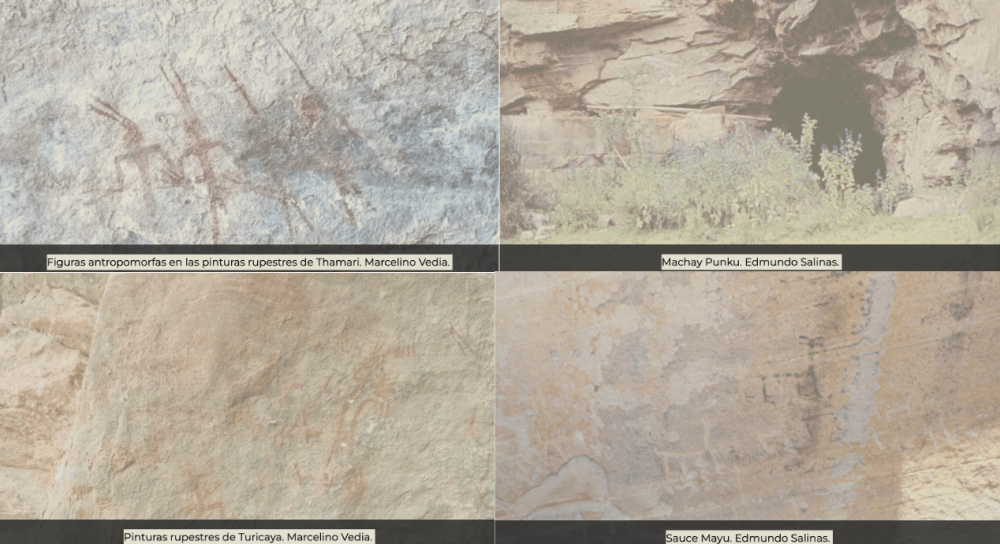

Around 2016, reports emerged of cave paintings or engravings in caves in Rural District 14 of the municipality of Potosí. The only person who gave them real importance was tour guide Marcelino Vedia who, once he became a city councilman, contacted Castaño and invited him to visit Potosí.

The Colombian anthropologist arrived in 2018, inspected the cave paintings, photographed them, and took notes to prepare a report on his observations. His estimation is extraordinary: he believes the paintings are at least 10,000 years old.

Before drafting his report on the Potosí cave inspection, Castaño responded to a questionnaire I sent him by email:

1. What area of Potosí did you visit?

A. Thamari, Arroyo Pulka, near the town of Turicaya.

2. What is the estimated age of the cave paintings you observed?

A. They belong to an American Paleoindian cultural tradition—Chiribiquete Tradition (Colombia) and Nordeste Tradition (Brazil)—dated around 10,000 years Before Present (BP).

3. Did you find any other traces of pre-Hispanic peoples or settlements?

A. This is a tradition of hunter-gatherer groups linked to Brazil’s Cerrado and Caatinga regions and the Amazonian tepui formations in Colombia, whose most evident cultural expression today is their hyper-realistic rock art.

4. Is it possible to determine which peoples or cultures the paintings or remnants belong to?

A. As stated for Brazil and Colombia: very ancient peoples that demonstrate a broad distribution across South America.

5. Feel free to add anything else not covered by these questions.

A. The significance of this new Thamaro-Pilka site is that it allows us to correlate it with my ongoing research on the Chiribiquete Cultural Tradition over the past three decades in the Colombian Amazon, and with the Nordeste Tradition of Brazil (in the states of Rio Grande and Piaui). My current scientific data documents a vast cultural heritage that confirms the existence of this tradition, from which we inherit many symbolic and iconographic elements related to American jaguar symbolism and a large, mobile, and highly adaptive population.

Castaño explains in an electronic publication dedicated to the study of Latin American rock art that Chiribiquete is an archaeological cultural tradition based on discoveries of more than 200,000 cave drawings in the mountain range of the Colombian Amazon.

“The rock art discovered so far reveals a series of features that have helped define a Cultural Tradition with apparently very ancient Paleoindian roots, and therefore linked to hunter-gatherer groups of the Tropical Humid Forest and semi-arid enclaves of the Guianas and Amazon,” he explains on the Rupestreweb portal.

The Paleoindian period spans from 40,000 to 10,000 BP, and the average age of the Chiribiquete Cultural Tradition is 19,500 BP. What Castaño calls “jaguarity” refers to iconography that “shows a surprising rigor in the depiction of human-animal relationships, access to power and energy exchanges through shamanic rituals, and emphasizes the prominence of the jaguar figure as one of the most important symbols of power, knowledge, skill, and the sharpness of hunters and warriors.”

MIGRATION

The findings in Potosí confirm that the migratory process that reached present-day South America continued onward. While some groups settled in Chiribiquete, others moved further south. Castaño concluded that the cave paintings in Potosí date back 10,000 years BP. This means that, as colonizing groups moved south, they reached and settled in this area around that time. Given the route taken, it is also possible that these groups settled in territories between the Colombian Amazon and the Potosí highlands—and perhaps continued migrating even further south. This lends Chiribiquete exceptional value for all humanity.

Despite the immense significance of these revelations, the authorities in Potosí failed to recognize it. The discovery remained merely a report. At the regional level, this lack of impact is understandable, but it is more troubling that there was no national response.

If the migration reached Potosí, it is logical to assume it passed through other regions in what is now Bolivia, including Chuquisaca.

Researcher Edmundo Salinas, who has visited nearly every archaeological site in southern Bolivia, states that “in Chuquisaca, we have identified more than 100 sites with rock art.” However, he has not linked those sites to time periods or social formations, as there is no evidence to do so. In Potosí, he says, more than 40 sites with cave art have been identified in the following areas: in the north, the provinces of Charcas and Chayanta (Toro Toro, Ravelo); in Tomás Frías province, near the city of Potosí, including Tarapaya; in the northwest, Quijarro and Daniel Campos provinces; in the southeast, Nor Chichas, Sud Chichas, and Modesto Omiste; and in the southwest, Nor Lípez and Sud Lípez.

What’s needed now is funding for research to determine which of these sites are connected to the Chiribiquete tradition.

(*) Juan José Toro is the founder of the Historical Research Society of Potosí (SIHP).

Por Juan José Toro Montoya, Correo del Sur:

Pinturas rupestres encontradas en el sur de Bolivia revelan asentamientos humanos con una antigüedad de aproximadamente 10.000 años

Con Bolivia acercándose cada vez más al bicentenario de su independencia, ya ha quedado claramente establecido que en este territorio existieron varias culturas que se desarrollaron mucho antes de ser alcanzadas por la invasión del denominado imperio incaico.

En el caso de Chuquisaca, la cultura que ha sido y es estudiada es la yampara, pero en el resto del departamento existieron otras, como charcas, que dejaron testimonios de su existencia y ahora son objeto de estudio de la arqueología. Mejor suerte corrió Potosí ya que, gracias a documentos coloniales como el Memorial de Charcas y las probanzas de decenas de personas seculares se sabe que en este departamento florecieron por lo menos ocho culturas claramente identificables: qaraqaras, karankas, killakas, lípez, suras, chichas, chuis y la ya citada charcas.

Aceptada como está la existencia de estas culturas, ¿cuál es su origen? Aquí es pertinente apuntar que la teoría mayoritariamente aceptada sobre el origen del hombre americano es la inmigracionista; es decir, la que postula que América se pobló con oleadas migratorias que llegaron desde Asia, África o Europa, ya sea en tiempos del supercontinente Pangea o bien aprovechando el hielo que cubrió las aguas del hoy estrecho de Bering.

PATRIMONIO DE LA HUMANIDAD

Las oleadas migratorias ingresaron a nuestro continente por Beringia, el puente que se formó entre el oeste de Alaska y el extremo oriental de Siberia durante el periodo glacial en lo que hoy es el estrecho de Bering, se establecieron inicialmente en el norte y fueron asentándose, paulatinamente, en el territorio que hoy es América. Hace unos 40.000 años ingresaron a la actual Norteamérica y, mientras unos grupos se quedaron, estableciendo colonias, otros siguieron avanzando hacia Centroamérica y, finalmente, llegaron a Sudamérica en un proceso que duró miles de años.

Se estima que hace unos 20.000 años llegaron a lo que hoy es la serranía o sierra de Chiribiquete, un grupo de mesetas rocosas que están en una zona que comprende no solo la Amazonía colombiana sino también la brasileña.

La serranía de Chiribiquete está ubicada en los departamentos colombianos de Caquetá y Guaviare y está atravesada por la línea del Ecuador, exactamente por la mitad, es decir, es la mitad del mundo, su centro. Allí, el antropólogo Carlos Castaño Uribe encontró pinturas rupestres cuya antigüedad ha sido cifrada en 22.000 años. Eso demuestra que las grandes migraciones llegaron a ese lugar durante este periodo.

La importancia del hallazgo es tal que Chiribiquete ha sido inscrita en la lista del patrimonio natural y cultural de la Unesco.

EN POTOSÍ

Hacia 2016 se reportó la existencia de pinturas rupestres o grabados en cuevas ubicadas en el distrito rural número 14 del municipio de Potosí. El único que les dio importancia fue el guía Marcelino Vedia que, cuando llegó a ser concejal, contactó a Castaño y lo invitó a visitar Potosí.

El colombiano llegó en 2018, inspeccionó las pinturas rupestres, les tomó fotografías y levantó apuntes para elaborar un informe sobre lo que vio y su estimación es poco menos que increíble: afirma que su antigüedad es de por lo menos 10.000 años.

Antes de redactar su informe sobre la inspección que realizó a las cuevas de Potosí, Castaño respondió al siguiente cuestionario que le envié por correo electrónico:

1.- ¿Cuál fue el área de Potosí que visitó?

RESPUESTA (R).- Thamari, Arroyo Pulka, próximo a la población de Turicaya,

2.- ¿Cuál es la antigüedad de las pinturas rupestres que pudo ver?

R.- Hacen parte de una tradición cultural del paleoindio americano, Tradición Chiribiquete (Colombia) Tradición Nordeste (Brasil) ubicada sobre entre el 10.000 Antes del Presente (AP).

3.- ¿Se encontró con algún otro vestigio de pueblos o asentamientos prehispánicos?

R.- Esta es una tradición de grupos cazadores-recolectores asociados con la Región del Cerrado y la catinga brasileña y con las formaciones tepuyanas amazónicas en Colombia, cuya expresión cultural más palpable en la actualidad es su hiperrealista arte rupestre.

4.- ¿Es posible determinar a qué pueblos o culturas pertenecen esas pinturas y/o vestigios?

R.- Lo ya indicado para el caso de Brasil y Colombia: pueblos muy antiguos que demuestran una amplia distribución en Suramérica

5.- Es usted libre de agregar algo más que no hubiere sido contemplado en las preguntas.

R.- La importancia de este nuevo registro de Thamaro-Pilka es que permite correlacionar este sitio con las investigaciones de la Tradición Cultural Chiribiquete que estoy haciendo desde hace tres décadas en la Amazonia Colombiana y con la tradición Nordestina de Brasil (estados de Rio Grande y Piaui). La información hoy disponible en mis investigaciones científicas permite documentar un gran acervo patrimonial que corrobora la existencia de esta tradición cultural a la que debemos muchos elementos simbólicos e iconográficos asociados a la jaguaridad americana y a una compleja y numerosa población de gran movilidad y sentido adaptativo.

El propio Castaño explica, en una publicación electrónica especializada en la investigación del arte rupestre de América Latina, que Chiribiquete es una tradición cultural arqueológica establecida sobre la base de los hallazgos de más de 200.000 dibujos en cuevas de la serranía de la Amazonía colombiana.

“El arte rupestre descubierto hasta el momento denota una serie de características que han servido para distinguir una Tradición Cultural de raíces, aparentemente muy antiguas, del paleoindio y, por ende, asociado a grupos de cazadores recolectores de Selva Húmeda Tropical y enclaves semisecos de las Guyanas y la Amazonía”, explica en el portal Rupestreweb.

El paleoindio es el espacio de tiempo comprendido entre los 40.000 y 10.000 años AP y la antigüedad promedio de la Tradición Cultural Chiribiquete es de 19.500 AP. Lo que Castaño denomina “jaguaridad” es “la iconografía (que) demuestra un rigor sorprendente respecto de las relaciones hombre-animales, el acceso al intercambio de poderes y energías a través de ritos chamánicos y se destaca profundamente la prelación de estos artífices por la figura del jaguar como uno de los elementos icnográficos más importantes de la distinción del poder y el conocimiento, así como las habilidades y la agudeza de los cazadores y los guerreros”.

MIGRACIÓN

Los hallazgos en Potosí demuestran que el proceso migratorio que llegó al territorio de la actual Sudamérica prosiguió ya que mientras unos grupos se asentaban en Chiribiquete, otros seguían avanzando hacia el sur. Castaño estableció que las pinturas rupestres potosinas tienen una antigüedad de 10.000 años AP. Eso significa que, al seguir bajando hacia el sur, los grupos colonizadores llegaron a estas tierras y se establecieron más o menos en el tiempo referido. Por la dirección que siguieron, no se descarta que se hayan establecido también en los territorios intermedios entre la Amazonía Colombiana y la serranía potosina e incluso hayan proseguido con el proceso migratorio hacia el sur. Eso le da a Chiribiquete un valor excepcional para la humanidad.

Pese al inmenso valor que tienen estas revelaciones, las autoridades potosinas no lo entendieron de esa forma, así que no pasaron de ser un simple reporte. Si eso pasó a nivel regional, hasta se entiende que no haya tenido repercusión nacional.

Si la migración llegó hasta Potosí, es lógico suponer que pasó por otras regiones del hoy territorio boliviano, incluido el departamento de Chuquisaca.

El investigador Edmundo Salinas, que ha recorrido casi todos los sitios arqueológicos del sur de Bolivia, dice que “en el territorio de Chuquisaca tenemos identificados más de 100 sitios con representaciones rupestres”, pero no ha relacionado los sitios inspeccionados con tiempos ni formaciones sociales debido a que no ha encontrado evidencia para tal fin. En el caso de Potosí, dice que se ha identificado más de 40 sitios con representaciones rupestres que se encuentran dispersos en las siguientes regiones: del norte, provincias Charcas, Chayanta (Toro Toro, Ravelo); provincia Tomás Frías, en las proximidades de la ciudad de Potosí, Tarapaya y otros; al noroeste Provincia Quijarro y Daniel Campos; al sudeste Nor Chichas, Sud Chichas y Modesto Omiste; al sudoeste Nor Lípez y Sud Lípez.

Lo que hace falta es financiar investigaciones que permitan determinar cuáles de esos lugares están vinculados con la tradición chiribiquete.

(*) Juan José Toro es fundador de la Sociedad de Investigación Histórica de Potosí (SIHP).

https://correodelsur.com/ecos/20250622/nuestros-antepasados.html