By Nature (2025):

Maize monoculture supported pre-Columbian urbanism in southwestern Amazonia

Abstract

The Casarabe culture (500–1400 CE), spreading over roughly 4,500 km2 of the monumental mounds region of the Llanos de Moxos, Bolivia, is one of the clearest examples of urbanism in pre-Columbian (pre-1492 CE) Amazonia. It exhibits a four-tier hierarchical settlement pattern, with hundreds of monumental mounds interconnected by canals and causeways1,2. Despite archaeological evidence indicating that maize was cultivated by this society3, it is unknown whether it was the staple crop and which type of agricultural farming system was used to support this urban-scale society. Here, we address this issue by integration of remote sensing, field survey and microbotanical analyses, which shows that the Casarabe culture invested heavily in landscape engineering, constructing a complex system of drainage canals (to drain excess water during the rainy season) and newly documented savannah farm ponds (to retain water in the dry season). Phytolith analyses of 178 samples from 18 soil profiles in drained fields, farm ponds and forested settings record the singular and ubiquitous presence of maize (Zea mays) in pre-Columbian fields and farm ponds, and an absence of evidence for agricultural practices in the forest. Collectively, our findings show how the Casarabe culture managed the savannah landscape for intensive year-round maize monoculture that probably sustained its relatively large population. Our results have implications for how we conceive agricultural systems in Amazonia, and show an example of a Neolithic-like, grain-based agrarian economy in the Amazon.

Main

The role of grain agriculture as the subsistence base of prehistoric complex societies in both the Old and New World has been a matter of sustained debate for many decades (see, for example, refs. 4,5,6,7,8). In Mesoamerica, the earliest evidence of maize as a staple crop dates to 4,000 calendar years before the present9. The timing and nature of maize’s role as the staple crop of Andean civilizations, as seen in early historical accounts, is controversial (see, for example, refs. 6,10). In Amazonia it is well established, from both archaeological and palaeoecological data, that maize has been cultivated since at least 6,850 calendar years before the present11; however, to date there is no evidence of it being a staple crop. Most societies had mixed economies relying on multiple cultigens12,13,14,15,16. Roosevelt17 proposes that the rise of social complexity in the Amazon was based on maize agriculture. However, current archaeological evidence has not been conclusive of maize cultivation being the staple crop of complex societies of the Amazon15. Current archaeobotanical and palaeoecological data from Late Holocene complex societies in Amazonia indicate polyculture (mixed-cropping) agroforestry, not maize monoculture, as the basis of a subsistence economy15,18,19,20,21,22.

Recent archaeological research has revealed evidence for low-density urbanism, social complexity and large populations in the Andean foothills of the Upano River region of Ecuador23, and in the monumental mounds region (MMR) in the seasonally flooded savannahs of the Bolivian Amazon1. Here in the MMR, the Casarabe people built hundreds of monumental mounds interconnected by canals and causeways across a flat forest–savannah mosaic landscape dominated by seasonally flooded savannahs, with forests restricted to non-flooded palaeo-river levées. Whereas drained fields and terraces, built on extremely fertile volcanic soils, were clearly integral to low-density agrarian urbanism of the Upano region23, the type of farming system needed to sustain the Casarabe culture is still unknown. It has been proposed that the construction of drainage canals permitted cultivation of the relatively fertile sediments of the seasonally flooded savannahs of the MMR24 without the need for deforestation25. However, no agricultural fields or other food production systems have hitherto been found in connection with such canals, leaving unanswered the question of how the Casarabe people managed to feed its relatively large population. To address this issue, we combine remote-sensing imagery with a programme of coring, test pits, radiocarbon dating and pollen and phytolith analyses on both seasonally flooded savannahs and forest.

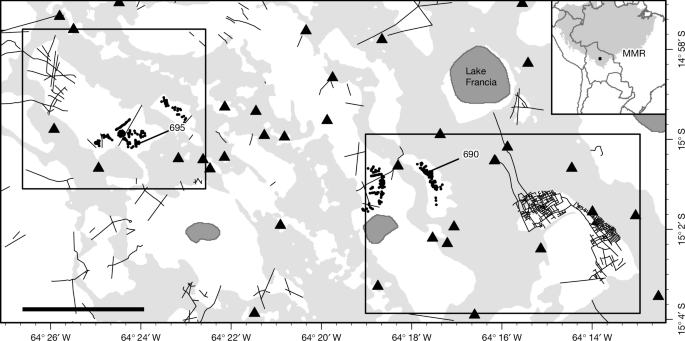

We have identified two unreported and complementary agrotechnologies in the savannahs of the MMR: dense drainage networks and artificial farm ponds (Fig. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 1), in which different portions of a savannah (Fig. 1, top left inset), or different savannahs within the same area (Fig. 1, bottom right inset), have been heavily modified—into either intricate arrangements of canals or clusters of circular depressions.

The drainage network

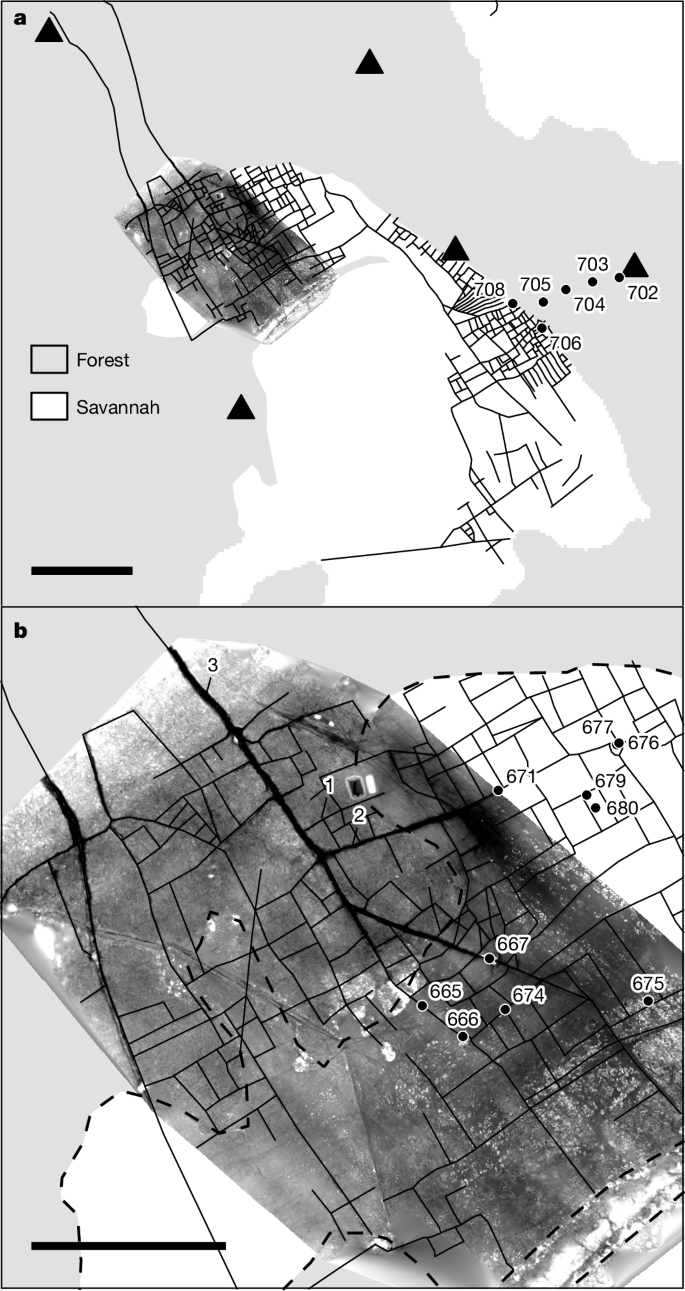

In one of the savannahs under study (Fig. 2), the small canals converge into larger canals that drain the whole savannah toward Lake Francia to the north (Fig. 1b). We identified three orders of drainage canals: the first order (1 in Fig. 2b), the smallest, are around 4 m wide and 25 cm deep, the second order (2 in Fig. 2b) are around 8 m wide and 70 cm deep and the main canal (third order) that drains into the lake is 14 m wide and 1.8 m deep (3 in Fig. 2b), becoming 3.2 m deep about 1.5 km before reaching the lake. Overall, the drainage network drains towards the north, becoming ever deeper with respect to the general topography. Several stratigraphic profiles of the canals show that the original depth of the canal network was around 80 cm deeper than at present for the second-order canals (see profiles 667 and 671 in Extended Data Fig. 2) and around 45 cm deeper for the first-order canals (for example, profile 674 in Extended Data Fig. 2). The drainage network is associated with circular elevated platforms roughly 50 cm in height, resembling pre-Columbian forest islands11, and with small mounds of around 2–3 m in diameter. The elevated platforms are surrounded by deep canals (profiles 666 and 677 in Extended Data Fig. 2).

Soil cores were collected from several locations both inside the canals and between them (Fig. 2b). Phytolith analysis shows a high abundance of phytoliths derived from the cob glumes and leaves of Zea mays in almost all canal soil profiles (Extended Data Fig. 2), with sporadic presence of Cucurbita spp. (666 and 677), Manihot sp. (677), Calathea sp. (674) and Lagenaria sp. (667) phytoliths. We cannot exclude the possibility that Cucurbita was cultivated in greater amounts than implied by the phytolith assemblage, because some domesticated Cucurbita varieties may lack scalloped phytoliths26.

…

[For full article, please use the link below]

Por Nature, Fernando Chávez, Visión 360:

Ciencia

Científicos descubrieron rastros de Casarabe, una civilización avanzada en la Amazonia de Bolivia

Arqueólogos determinaron que esa sociedad diseñó sistemas hidráulicos avanzados para sobrevivir en una región con inundaciones estacionales.

Estudios revelaron montículos que alcanzan los 20 metros de altura y cubren áreas de hasta 20 hectáreas. Foto: Stephen Rostain

Un estudio recientemente publicado por la revista Nature, liderado por el arqueólogo Umberto Lombardo, de la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, aportó pruebas de que la cultura Casarabe, asentada en los Llanos de Moxos, en el norte de Bolivia, desarrolló una sociedad compleja con avanzadas infraestructuras hidráulicas y prácticas agrícolas extensivas.

Los Llanos de Moxos, situados sobre el borde occidental de la selva amazónica, presentan un paisaje predominantemente plano, con periodos de inundación que pueden extenderse hasta seis meses al año. Esta particularidad llevó durante mucho tiempo a suponer que las condiciones del suelo eran “inadecuadas” para sustentar grandes asentamientos humanos, dice un reporte que publica Infobae, que cita a The Economist.

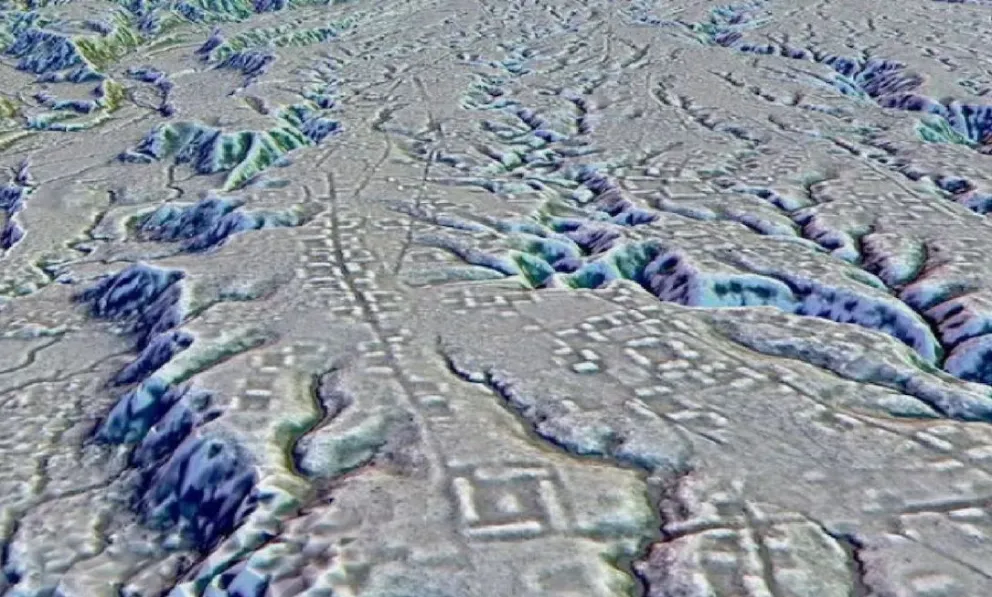

Sin embargo, la investigación encabezada por Lombardo puso en cuestión esta visión tradicional. Mediante el análisis de imágenes satelitales y tecnología LIDAR (detección y rango de luz), el equipo de arqueólogos identificó una amplia red de montículos artificiales, calzadas y canales interconectados.

Estas estructuras, atribuidas a la cultura Casarabe, sugieren que la región albergó un número significativo de habitantes que lograron adaptarse al entorno mediante ingeniería hidráulica avanzada y la domesticación de cultivos claves (como el maíz).

Las investigaciones en los Llanos de Moxos pudieron desvelar un sistema arquitectónico sorprendente que desafía la idea de la Amazonia como un territorio poco intervenido por civilizaciones precolombinas.

En el área conocida como la Monumental Mound Region, que abarca 4.500 kilómetros cuadrados, se identificaron cientos de montículos artificiales, algunos con más de 20 metros de altura y una extensión de hasta 20 hectáreas. Estas estructuras, estuvieron interconectadas por una red de calzadas que se extienden varios kilómetros, lo que sugiere una planificación urbana avanzada.

La ausencia de piedra en la región llevó a estos antiguos pobladores a edificar con tierra, técnica que permitió la creación de asentamientos elevados que resistían las inundaciones estacionales. Estos montículos sirvieron como bases para viviendas y centros comunitarios, además de que podrían haber tenido funciones ceremoniales o administrativas.

El alcance de estas construcciones sugiere una sociedad jerárquica con una capacidad organizativa significativa. La distribución de los montículos y su conexión mediante calzadas apuntan a un sistema de planificación territorial que facilitaba la movilidad y la interacción entre distintos sectores de la comunidad.

Además, la presencia de estas infraestructuras en un área tan extensa respalda la hipótesis de que la cultura Casarabe fue una civilización con una estructura social compleja y una estrategia eficaz para habitar un entorno desafiante.