By Leny Chuquimia, Vision 360:

In the midst of the crisis

Producers explain that the crisis has increased production costs, but not to the extent seen in the markets. They are calling for channels to reach the population directly.

Producers and consumers, the most affected by speculation. Photo: Leny Chuquimia / Visión 360

Between one and six in the morning, Calle 5 in Villa Dolores in El Alto, the streets adjacent to the Rodríguez Market in La Paz, or El Tejar near the General Cemetery, fill with trucks loaded with vegetables, tubers, and other produce. Hundreds of farmers arrive in the cities with products freshly harvested from their fields.

In the middle of the night, depending on the scarcity or abundance of certain products, a battle of offers and counteroffers takes place. There, every day, the prices are set at which intermediaries—wholesalers and retailers—will purchase the products, which they will later distribute in different markets at nearly double their investment.

“There’s speculation. We’re selling a quarter of onions for five bolivianos. To the wholesaler, it’s much cheaper, sold at 3.50. But in the market and stores, they already sell it for eight and even 10 bolivianos. They’re making almost double… that doesn’t go to the producer and it also affects the population,” says Sonia Quispe, a producer who comes to El Alto from Oruro.

The coordinator of the Semilla Ecosocial project, Fabrizio Uscamayta, asserts that while the increase in production costs is real, what is being seen in the markets is a process of speculation due to the lack of a direct channel between producer and consumer. He identifies the monopoly that intermediaries have over the main supply centers as one of the biggest problems.

“They have very strong organizations with highly vertical power structures. These are corporate networks that do not allow producers to participate directly in the market, in any space. There is no real farmers’ market either in La Paz or in Bolivia,” he states.

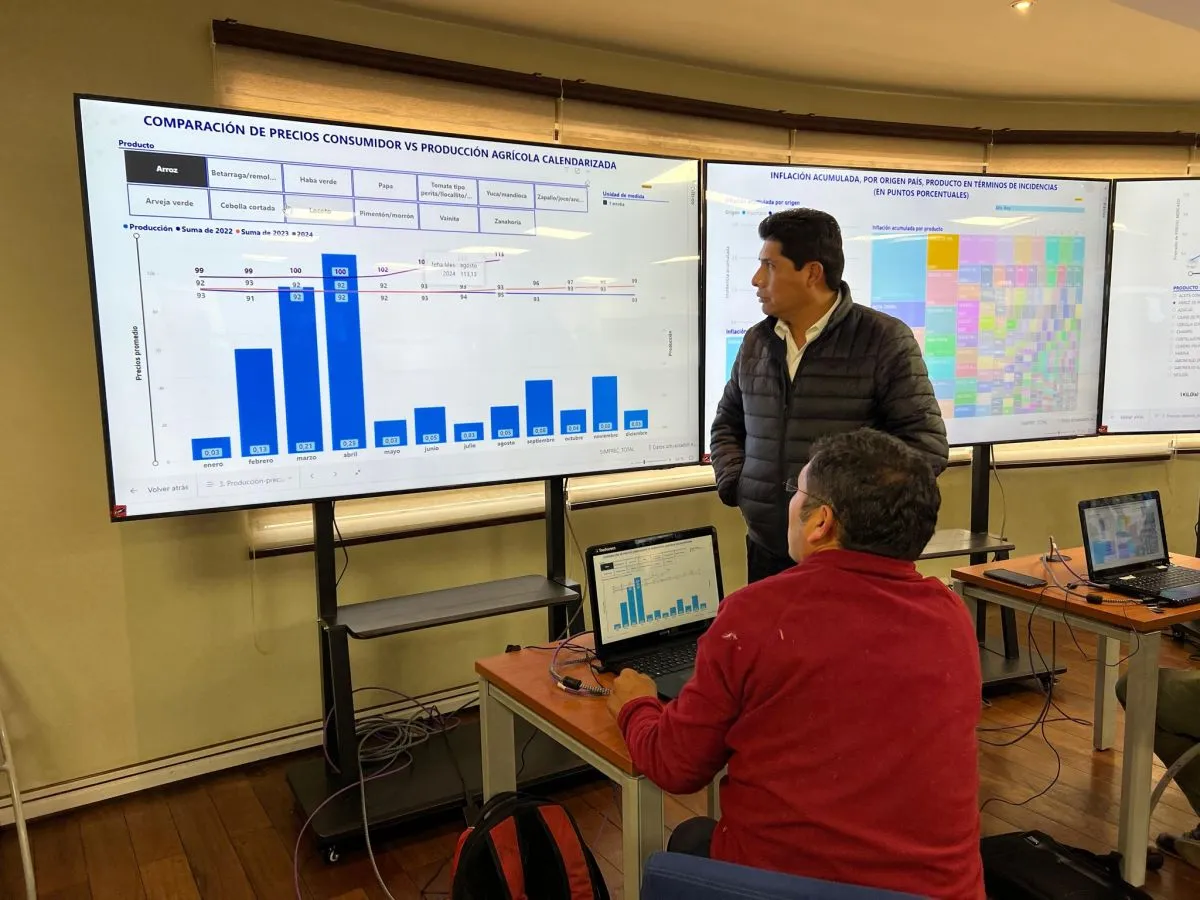

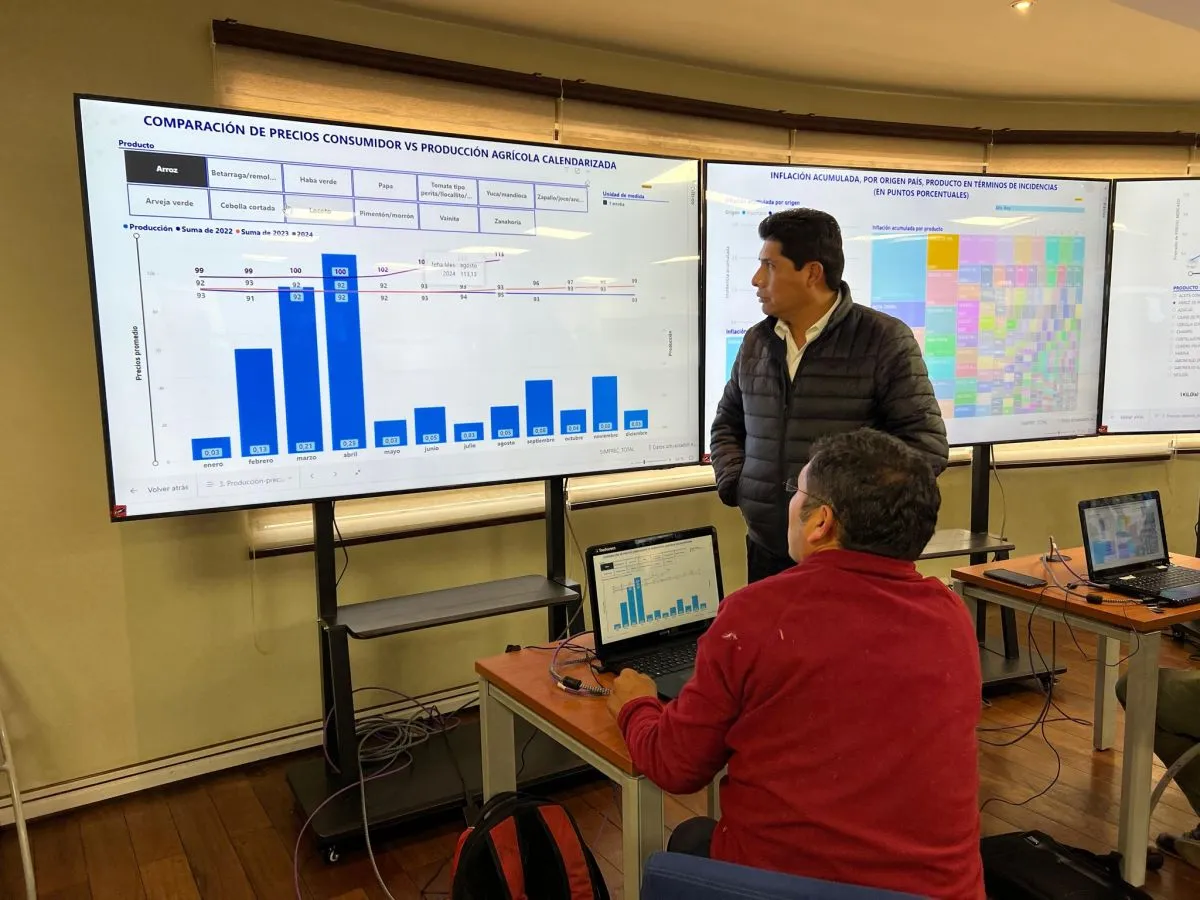

For the government, these links in the chain, in addition to speculation, are also engaging in reverse smuggling. That is, they are taking products to the borders, thereby depleting the domestic market. As measures, price controls, border controls, and the implementation of a food security monitoring system have been initiated.

Duplication of Profits with Price Hikes

During the week, in an operation, the municipal inspector of Potosí, Jhimy Bedoya, found several vendors who had raised the prices of products without justification. The most notable case was that of chicken.

“They were selling it for 17 to 18 bolivianos, when the chicken cost 14.50 bolivianos per kilo. It should be sold for 15.50 and at most 16 bolivianos per kilo. They were doubling their profits,” says Bedoya.

In La Paz, a similar measure led to a confrontation between several vendors at a central market and the Municipal Inspection staff. The reason was their refusal to display the price list for public inspection.

“Everything has gone up, but it’s easier to control groceries, cleaning products, or imported goods,” explains a vendor from the Ciudad Satélite market in El Alto. She hurriedly arrived at the “From the Field to the Pot” fair, a government measure to curb price increases.

“We have invoices, which can justify how much the product and its transportation have increased and how much more can be added to the customer’s price. It’s easy to determine if there is abuse. But vegetables don’t come with invoices; there is no purchase order to know how much the producer charged or how many intermediaries they passed through. Within the market, it’s more expensive than at this fair, almost double,” she asserts.

Uscamayta notes that it’s also important to consider that transporters are among the intermediaries. “They increased their costs not because diesel prices went up, but because the scarcity led to additional expenses, such as having to wait in lines for several days or weeks. Most drivers are not owners and must pay daily rent. This increases the cost of transporting goods to the market,” he explains.

The increase for the producer

“Yes, our costs have increased. Without fuel, we can’t operate our machinery. Inputs are purchased at the dollar exchange rate. There is less production due to the drought, and also because we are in winter. All of this means there are fewer products and therefore they are more expensive, but we have to absorb those costs,” says Andrés Aguilar, Vice President of the Mercado Integración Sur, from Cochabamba.

While speculation is a factor, it is not the only one contributing to the rise in food prices. The fuel crisis, shortage of dollars, lack of transportation, climatic events, and social conflicts have caused increases and serious losses in crops. However, this increase is borne by the producer, as the amount paid by the final consumer does not reach them.

“What should be clear is that the small producer has always subsidized the population’s food supply,” says Uscamayta.

He explains that this is a very complex situation with many facets. He divides small farmers into three groups. One is the small family agriculture linked to agribusiness, such as oilseed producers.

The second group consists of traditional producers from the inter-Andean valleys of Cochabamba, Santa Cruz, La Paz, and the Altiplano. The third, the smallest group, is made up of family farmers with an agroecological approach.

“Each of these three groups is impacted differently. The first group has a structural dependence on agrochemicals, which are 100% imported, both legally and illegally, hence their input costs rise. The same applies to valley producers who use agrochemicals to sustain their production and fuel for their machinery. It is a reality that their input costs are rising, and thus the price of their products,” he says.

In the case of agroecological farming, since they produce their own inputs for weed and pest control, their production costs do not increase. However, they represent only 1% of the market, so the increase is felt by the remaining 99%.

“While the increase in production costs is real, what we are seeing in the markets now is a process of speculation due to the lack of a direct channel between producers and consumers. The increase is real, but not at the level we see, with increases of 200%, 300%, or even 400%, amounts that do not reach the producing families.”

From Producer to Consumer

On Wednesday morning, dozens of producers arrived at Tinku Square in Ciudad Satélite as part of the “From the Field to the Pot” fair. The initiative aims to put producers in direct contact with consumers.

By Friday, the Vice Ministry of Agricultural Development had conducted 18 of these events across the nine departments of the country. A total of 320.9 tons of food were sold, including fruits, tubers, vegetables, meats, and other items.

“These fairs are very important for us; we understand that intermediaries and market vendors need to earn their income, but there are unjustified increases. We cannot enter the markets, and now they even came to bother us about our prices,” says Dora, a producer from Achocalla who participated in the state fair.

Like Dora, Uscamayta and Aguilar point out that this is the solution: markets from producer to consumer. However, they state that these should not be temporary but permanent.

The request is not new. In 2019, several regions in Bolivia experienced a potato overproduction. What seemed to be a year of good profits for small producers turned into a season of losses.

Victims of large intermediaries had to lower the price of their potato harvest to 15 bolivianos per arroba. “There’s so much,” “I’ll buy from someone else,” they were told to get the price reduced.

But in urban markets, the price was 30 to 40 bolivianos, an unjustified increase. The producers’ request was to have their own markets.

“It’s possible,” says Aguilar. The Cochabamba producer is vice president of the Mercado Integración Sur in Cochabamba, a private space managed by producers to bypass the monopoly of intermediaries.

In the early hours of each Tuesday and Thursday, hundreds of trucks arrive at this market, which now has a TikTok account run by the new generations. It was their parents, tired of wandering and falling victim to wholesale prices, who decided to purchase land to set up their own market.

“To have the market, we spent years on the streets. As true peasant producers, we saw the need to have our own space and not depend on anyone. We wanted to sell our products at a fair price and have a dignified life. Here in Tamborada, we have the market; we manage and run our own space and improve our income,” he explains.

Yes, it is possible to create fairer trade

Mercado Integración Sur is not the only example of a short supply chain. With a similar objective but an agroecological focus, Ecotambo was also created.

“Ecotambo has a fair in a short supply chain. Producers can offer their products permanently, with an agroecological focus,” explains Uscamayta.

Ecotambo is a self-managed association of urban, peri-urban, and rural producers, social enterprises from the La Paz department, and agroecological consumers. They work every day with the goal of promoting a healthy, fair, and pesticide-free food system, encouraging local trade, proximity, and responsible consumption.

They started in April 2020, during the pandemic, as a way to find alternative sales channels during food shortages. Due to movement restrictions, they began with a home delivery service, and today orders can be placed online.

This experience allowed the democratization and diversification of food marketing methods.

“Our work is based on the short supply chain model, where the prices we handle aim for local and stable trade for producer families and consumers, making us a real mechanism for fair trade,” says Uscamayta.

From his perspective, an alternative model of agroecological production and consumption is possible.

Who is responsible for controlling prices?

“The cost of the basic food basket has risen, and the issue with fuels is a mess. Government measures are short, medium, or long-term, but we need immediate actions (…). We demand that the municipality, the Municipal Guard, and Consumer Protection control speculation and hoarding. They are hiding goods,” denounced Marcelo Mayta, executive secretary of the Regional Workers’ Central of El Alto.

In the municipality of La Paz, the faction of the Federation of Neighborhood Boards led by Justino Apaza stated that if there are no controls, neighbors will take to the streets to conduct “raids.”

“We are organizing to identify, market by market, those who are hiding basic food products or raising prices,” he said.

But who is responsible for carrying out these controls? By standard, markets or supply centers are under municipal control. However, the production chain is so extensive that multiple state institutions at different levels need to intervene, especially in light of the crisis the country is facing.

With this understanding, the Inter-Institutional Food Security Committee was created. It includes the Vice Ministries of Rural and Agricultural Development, Internal Commerce, Consumer Protection, Anti-Smuggling, Industrialization Policies, and Planning, as well as the National Institute of Statistics (INE). One of its actions is to conduct coordinated controls with municipalities, departments, the police, and other institutions.

“The controls being carried out in La Paz’s markets are mutual; it’s a shared responsibility in a comprehensive plan to combat profiteering and speculation. We need to coordinate actions and require greater operational capacity,” said La Paz Mayor Iván Arias.

In the operations, the Bolivian Institute of Metrology and the National Service of Agropecuary Health and Food Safety also participate. Municipal staff is responsible for ensuring that prices are clearly displayed to prevent price manipulation and protect consumer rights.

Products flee to 3 countries; regulation will instruct seizure and sale at EMAPA

“There is a lot of speculation, mainly by intermediaries. They collect products to divert them from the domestic market and export them to increase their profits. A few profit at the expense of food security and consumers’ wallets,” said the Deputy Minister of Agropecuary Development, Álvaro Mollinedo.

As it is an illegal activity, exact figures are not available for how many tons leave the country illegally. However, according to production and consumption projections, it is estimated that around 100,000 tons of rice have already been diverted.

“It is not the mills or the producers who are exporting the product; it is the intermediaries,” said the authority.

Sugar, eggs, onions, potatoes, and even meat are among the products identified at borders with Argentina, Brazil, and Peru. The main reason is that these products have a much higher cost in these countries, creating an opportunity for smugglers.

Mollinedo said that the government is working on a supreme decree to regulate Law 100 on Border Development and Security. One of the gaps in smuggling control is that the law applies to those who enter, but not those who exit.

The new regulation aims to also control local foods that are illegally taken out of the country. With this tool, competent institutions will be able to confiscate and subsequently return the products to the domestic market.

All seized goods will be handed over to Emapa. According to what was explained, Emapa will be responsible for selling these products to the public at a “fair price and weight,” as stated by Mollinedo.

Shortening the supply chain: A solution with multiple tasks

When discussing solutions to speculation and potential future crises, Uscamayta is clear: “The supply chain needs to be shortened.” This requires not only markets but a series of urgent and structural changes.

“The first step is to have these markets for the producer, but spaces are required, and that is a structural problem,” he said.

Another important aspect is access and connectivity. In this regard, the condition of roads and routes that facilitate transportation is crucial, as well as the ability to move large quantities of food, since most producers are in dispersed areas and lack vehicles or access to storage spaces.

“Another problem is human capacity, the aging of family agriculture, and migration. A large part of the producers are women over 50 to 60 years old, so human capacity is low. It’s a structural problem,” he said.

But also, from his experience, he sees the need to eliminate subsidies to agribusiness and increase them for small family agriculture and agroecological food.

“Only in this way will we have a structural solution to the problem that lies ahead. It’s not just the crisis we’re experiencing or the issue of inputs. There’s a risk of increased climatic events; so far, there is no agricultural insurance to support small producers,” he stated.

Por Leny Chuquimia, Vision 360:

En plena crisis

Los productores explican que la crisis aumentó los costos de producción, pero no al punto que se ve en los mercados. Piden canales para llegar de forma directa a la población.

Productores y consumidores, los más afectados ante la especulación. Foto: Leny Chuquimia / Visión 360

Entre la una y seis de la mañana, la calle 5 de Villa Dolores de El Alto, las vías adyacentes al mercado Rodríguez en La Paz, o El Tejar en el Cementerio General, se llenan de camiones cargados de hortalizas, tubérculos y otras verduras. Cientos de productores llegan a las urbes con productos recién sacados de las chacras.

En medio de la madrugada, acorde a la escasez o demasía de determinados productos, se libra una guerra de ofertas y contraofertas. Ahí, cada día, se definen los precios con los que intermediarios -mayoristas y minoristas- se llevarán los productos, que horas más tarde, distribuirán en diferentes mercados, a un costo que casi duplica su inversión.

“Hay especulación. La cebolla estamos dando la cuarta a cinco bolivianos. Al mayorista a mucho más barato, salido a 3,50. Pero en el mercado y tiendas ya venden a ocho y hasta 10 bolivianos. Están sacando casi el doble… eso no va al productor y además afecta a la población”, dice Sonia Quispe, productora que llega a El Alto desde Oruro.

El coordinador del proyecto Semilla Ecosocial, Fabrizio Uscamayta, afirma que si bien el incremento de costos de producción es real, lo que se está viendo en los mercados es un proceso de especulación, debido a la falta de un canal directo entre productor y consumidor. Identifica como uno de los mayores problemas el monopolio que los intermediarios tienen sobre los principales centros de abasto.

“Tienen organizaciones muy fuertes de estructuras de poder muy verticales. Son redes corporativas que no permiten que el productor participe en el mercado de manera directa, en ningún espacio. No hay un mercado campesino real ni en La Paz ni en Bolivia”, manifiesta.

Para el Gobierno, estos eslabones de la cadena, además de la especulación están incursionando en el contrabando a la inversa. Es decir que sacan productos a las fronteras desabasteciendo el mercado interno. Como medidas se han empezado los controles de precios, el control en fronteras y la aplicación de un observatorio de seguridad alimentaria.

Foto: Leny Chuquimia / Visión360

Duplican ganancias con el alza de precios

En la semana, en un operativo, el intendente municipal de Potosí, Jhimy Bedoya, encontró varios vendedores que elevaron el precio de los productos sin justificación. El caso más notorio fue el del pollo.

“Estaban vendiendo en 17 bolivianos y hasta en 18, cuando el pollo llegó a 14,50 bolivianos el kilo. Debería venderse en 15,50 y máximo en 16 bolivianos el kilo. Estaban duplicando sus ganancias”, afirma Bedoya.

En La Paz, una medida similar desencadenó que varias vendedoras, de un mercado céntrico de la urbe, empezaran una discusión con el personal de la Intendencia Municipal. El motivo era que se negaban a tener la lista de precios exhibida para el control de la población.

“Todo ha subido, pero en los abarrotes, productos de limpieza o productos importados es más fácil controlar”, explica una vendedora del mercado de Ciudad Satélite de El Alto. Apresurada llegó a la feria “Del Campo a la Olla”, medida del Gobierno nacional para frenar el alza.

“Nosotros tenemos factura y con eso se puede justificar cuánto subió el producto y su transporte y cuánto más puede incrementarse el precio al cliente. Es fácil saber si hay abuso. Pero las verduras no vienen con factura, no hay orden de compra para saber a cuánto les dio el productor o por cuántos intermediarios pasó. Dentro del mercado está más caro que en esta feria, casi al doble”, asevera.

Uscamayta señala que también debe tomarse en cuenta que entre los intermediarios están los transportistas. “Ellos incrementaron sus costos, no porque el diésel haya subido, sino por la escasez que les generó varios gastos, como el hacer colas por varios días o semanas. En su mayoría, los choferes no son dueños, deben pagar la renta al día. Esto incrementa los costos del transporte de la producción al mercado”, explica.

El incremento para el productor

“Sí, nos han subido los costos. Sin combustible no podemos trabajar con nuestra maquinaria. Los insumos se compran al cambio del dólar. Hay menos producción por la sequía, además que estamos en invierno. Todo eso hace que haya menos productos y por tanto es más caro, pero eso lo asumimos nosotros” , afirma desde Cochabamba, Andrés Aguilar, vicepresidente del Mercado Integración Sur.

Si bien hay especulación, no es el único factor en el alza de los precios de los alimentos. La crisis de combustible, la escasez de dólares, la falta de transporte, los eventos climáticos y los conflictos sociales causaron un incremento y serias pérdidas en las siembras. Sin embargo, ese aumento es asumido por el productor, pues lo pagado por el consumidor final no llega a este.

Foto: Leny Chuquimia / Visión 360.

“Lo que debe quedar claro es que el pequeño productor siempre ha subvencionado la alimentación de la población”, sostiene Uscamayta.

Explica que esta es una situación muy compleja y llena de aristas. Divide a los pequeños agricultores en tres grupos. Uno es el de la pequeña agricultura familiar vinculada al agronegocio, como los productores de oleaginosas.

El otro está conformado por los productores tradicionales de los valles interandinos de Cochabamba, Santa Cruz, La Paz y el Altiplano. El tercero, el más pequeño, está compuesto por los de la agricultura familiar con enfoque agroecológico.

“Los tres grupos reciben impactos de forma diferente. El primero tiene una dependencia estructural a los agrotóxicos, que en un 100% son importados, de forma legal e ilegal, por eso suben sus insumos. Lo mismo ocurre con los productores de los valles que utilizan agroquímicos para sostener su producción y combustible para su maquinaria. Es una realidad que sus insumos están subiendo y por tanto el precio de sus productos”, indica.

En el caso de la agricultura agroecológica, debido a que ellos producen sus propios insumos para control de malezas, plagas, etc., no incrementan sus costos de producción. Pero ellos representan solo el 1% del mercado, por lo que se siente el incremento del restante 99%.

“Si bien el incremento de los costos de producción es real, lo que ahora vemos en los mercados es un proceso de especulación por la falta de un canal directo entre productores y consumidores. Es real incremento, pero no al nivel del que vemos, del 200%, 300% o hasta 400%, aumentos que no llegan a la familia productora”.

Del productor al consumidor

La mañana del miércoles, decenas de productores llegaron hasta la plaza del Tinku en Ciudad Satélite, como parte de la feria “Del Campo a la Olla”. La iniciativa busca poner en contacto directo al productor con el consumidor.

Hasta el viernes, el Viceministerio de Desarrollo Agropecuario realizó 18 de estas actividades, en los nueve departamentos del país. Se comercializaron 320,9 toneladas de alimentos, entre frutas, tubérculos, verduras, carnes y otros.

Foto: Leny Chuquimia / Visión 360.

“Estas ferias para nosotros son muy importantes; entendemos que los intermediarios y las vendedoras de los mercados tienen que ganar su ingreso, pero hay aumentos injustificados. Nosotros no podemos entrar a los mercados, incluso ahora vinieron a molestarnos por nuestros precios”, afirma Dora, productora de Achocalla que fue parte de la feria estatal.

Al igual que Dora, Uscamayta y Aguilar señalan que esta es la solución: mercados del productor al consumidor. Pero afirman que estos no deben ser eventuales, sino permanentes.

La petición no es nueva. En 2019, en varias regiones de Bolivia se vivió una sobreproducción de papa. Lo que parecía ser un año de buenas ganancias para los pequeños productores se convirtió en una temporada de pérdidas.

Foto: Leny Chuquimia / Visión 360.

Víctimas de los grandes intermediarios tuvieron que bajar el precio de su cosecha de papas a 15 bolivianos la arroba. “Tanto hay”, “voy a comprar de otro”, les decían para lograr la rebaja.

Pero en los mercados urbanos el precio era de 30 y 40 bolivianos, un incremento injustificado. El pedido de los productores fue el de tener mercados propios.

“Es posible”, dice Aguilar. El productor cochabambino es vicepresidente del Mercado Integración Sur de Cochabamba, un espacio privado y gestionado por los productores para saltar el monopolio de los intermediarios.

En la madrugada de cada martes y jueves, cientos de camiones llegan a este mercado que ya tiene una cuenta en Tik Tok, alimentada por las nuevas generaciones. Fueron sus padres que cansados de deambular, víctimas del precio de los mayoristas, decidieron adquirir un terreno en el que puedan instalar su propio mercado.

“Para tener el mercado andamos año tras año en las calles. Como verdaderos productores campesinos vimos la necesidad de tener un predio propio y no depender de nadie. Queríamos vender nuestros productos a un precio justo y tener una vida digna. Acá en la Tamborada tenemos el mercado, nosotros administramos y gestionamos nuestro espacio y mejoramos nuestros ingresos”, explica.

Sí es posible generar un comercio mas justo

El Mercado Integración Sur no es el único ejemplo de un canal corto. Con la similar objetivo, pero además un enfoque agroecológico, nació el Ecotambo.

“Ecotambo tiene una feria en una cadena corta. Los productores pueden ofrecer sus productos de forma permanente, además con enfoque agroecológico”, explica Uscamayta.

Ecotambo es una asociación autogestionada de productoras y productores urbanos, periurbanos y rurales, emprendimientos con fines sociales del departamento de La Paz y consumidores agroecológicos. Trabajan cada día con el objetivo de promover un sistema alimentario sano, justo y libre de agrotóxicos, fomentando el comercio local, cercano y el consumo responsable.

Empezaron en abril de 2020, durante la pandemia, como una forma de buscar alternativas de venta en tiempos de escasez de alimentos. Por las restricciones de movimiento empezaron con un servicio de entrega a domicilio, hoy ya se pueden hacer pedidos vía internet.

Esta experiencia permitió la democratización y diversificación de la forma de comercializar los alimentos.

“Nuestro trabajo se basa en la cadena corta de comercialización, donde los precios que manejamos persiguen un comercio local y estable para las familias productoras y consumidores, lo que nos convierte en un mecanismo real de comercio justo”, indica Uscamayta.

En su perspectiva, un modelo alternativo de producción y consumo agroecológico es posible.

¿A quién le corresponde controlar los precios?

“El costo de la canasta familiar subió y el tema de combustibles es un caos. Las medidas del Gobierno son a corto, mediano o largo plazo, pero necesitamos acciones inmediatas (…). Exigimos al municipio, la Guardia Municipal y Defensa del Consumidor, controlar el agio y especulación. Están escondiendo víveres”, denunció el secretario ejecutivo de la Central Obrera Regional de El Alto, Marcelo Mayta.

En el municipio de La Paz, la facción de la Federación de Juntas Vecinales, encabezada por Justino Apaza, señaló que de no haber controles, serán los vecinos los que salgan a las calles a realizar “batidas”.

“Nos estamos organizando para identificar, mercado por mercado, a quienes están ocultando los productos de la canasta familiar o están subiendo los precios”, indicó.

Pero ¿quiénes son los responsables de hacer estos controles? Por norma los mercados o centros de abastos están bajo control de los municipios. Sin embargo, la cadena de producción es tan amplia que son varias las instituciones de diferentes niveles del Estado que deben intervenir, más aún ante la crisis que vive el país.

Bajo este entendido, se creó el Comité Interinstitucional de Seguridad Alimentaria. Está conformado por los viceministerios de Desarrollo Rural y Agropecuario, de Comercio Interno, de Defensa del Consumidor, de Lucha Contra el Contrabando, de Políticas de Industrialización y de Planificación, además del Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Una de sus acciones son los controles coordinados con los municipios, gobernaciones, la Policía y otras instituciones.

“Los controles que se están haciendo en los mercados de La Paz son mutuos; es una responsabilidad compartida en un plan integral para combatir el agio y la especulación. Tenemos que coordinar acciones, necesitamos mayor capacidad operativa”, afirmó el alcalde de La Paz, Iván Arias.

En los operativos también participan el Instituto Boliviano de Metrología y el Servicio Nacional de Sanidad Agropecuaria e Inocuidad Alimentaria. El personal edil se encarga de verificar que los precios estén claramente exhibidos, para que no haya manipulación de los valores y proteger así los derechos de los consumidores.

Productos fugan a 3 países; norma instruirá comiso y venta en Emapa

“Hay mucha especulación, principalmente, por los intermediarios. Estos se dedican a acopiar para desviar los productos del mercado interno y sacarlos fuera del país para incrementar sus ganancias. Unos cuantos lucran a costa de la seguridad alimentaria y el bolsillo de los consumidores”, dijo el viceministro de Desarrollo Agropecuario, Álvaro Mollinedo.

Al ser una actividad ilícita, no se tienen cifras exactas de cuántas toneladas salen ilegalmente del país. Pero, de acuerdo con las proyecciones de producción y consumo, en el caso del arroz, se estima que ya fueron desviadas alrededor de 100 mil toneladas.

“No son los ingenios ni los productores los que sacan el producto, son los intermediarios”, sostuvo la autoridad.

Azúcar, huevo, cebolla, papa y hasta carne son otros de los productos que fueron identificados en las fronteras con Argentina, Brasil y Perú. El motivo principal es que estos productos tienen un costo bastante elevado en estos países, lo que implica una oportunidad para los contrabandistas.

Mollinedo dijo que desde el Gobierno se trabaja en un decreto supremo que reglamente la Ley 100 de Desarrollo y Seguridad Fronteriza. Y es que uno de los vacíos en el control de contrabando es que la ley es para el que ingresa y no así para el que sale.

Con la norma se busca que también se controlen los alimentos locales que sean sacados de forma ilegal fuera de las fronteras. Con esta herramienta, las instituciones competentes podrán realizar decomisos y posterior retorno de los productos al mercado interno.

Para ello, todo lo incautado será entregado a Emapa. De acuerdo con lo explicado, será la estatal la que se encargue de vender estos productos a la población, a un “precio y peso justo”, según indicó Mollinedo.

Acortar la cadena, una solución con varias tareas

Cuando se habla de dar solución a la especulación y a la crisis que pueden darse a futuro, Usamayta es claro: “Se debe acortar la cadena”. Para ello no basta con mercados, sino con una serie de tareas y cambios urgentes y estructurales.

“Lo primero es tener estos mercados para el productor, pero para ello se requieren espacios y ese es un problema estructural”, afirmó.

Foto: Leny Chuquimia / Visión 360.

Otro de los aspectos importantes es el acceso y conexión. En este punto es primordial el tema de las carreteras y vías que faciliten el tema de transporte, pero también la forma de mover grandes cantidades de alimentos, puesto que la mayoría de los productores están en zonas dispersas y no cuentan con vehículos o acceso a espacios de acopio.

“Otro problema son las capacidades humanas, envejecimiento de la agricultura familiar y la migración. Gran parte de los productores son mujeres que están por encima de los 50 a 60 años y, por tanto, las capacidades humanas son bajas. Es un problema estructural”, dijo.

Pero también, desde su experiencia, ve necesaria la eliminación de subvenciones al agronegocio, para incrementarlas a la pequeña agricultura familiar y al alimento agroecológico.

“Solo así tendremos una solución estructural para el problema que se nos avecina. No solo es la crisis que estamos viviendo o el problema de los insumos. Hay riesgo del incremento de eventos climáticos; hasta ahora no hay un seguro agrícola que respalde a los pequeños productores”, sostuvo.