Juan José Toro Montoya, El Potosi:

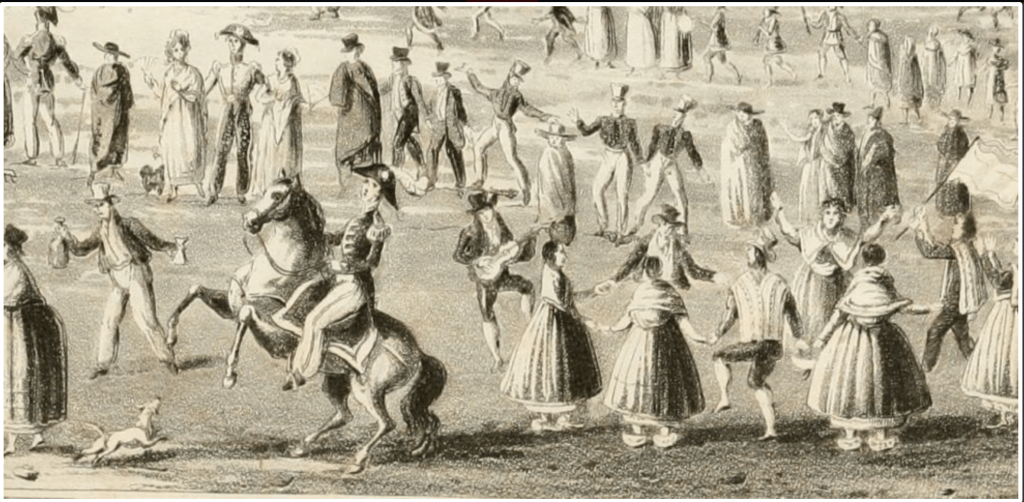

Detalle del grabado del carnaval potosino en el libro de Temple.

Playing with water is a recent element in the traditions of the Potosí carnival

Until at least 1827, this activity was not part of our shrovetide.

People who believe that water play is part of the Potosí carnival traditions would be surprised if they knew that documents and publications prove that this activity was only added to these festivities in Republican times, so it can be considered a recent addition. .

The scarcity of water has determined that this year the ban on playing with water was ratified and even the governor issued a decree extending it to the entire departmental territory. Among the people protesting are those who say that water play is only during carnival, while mining mills and car washes consume the liquid all year round, with little or no control. Another argument is that this game would be part of the carnival traditions and therein lies the error.

Potosí is a city with little water supply and, therefore, it always suffered from the scarcity of that liquid. Because of this, no one would have thought of wasting it by dunking other people at carnival. In the agreement books of the Secular Archive of Potosí there are several provisions on water, but most of them are intended to take care of the liquid, or distribute it in a better way.

The use that mills made of water is a centuries-old problem. In an agreement of June 3, 1591, for example, it is recommended that not so much water be given to them. In 1635, Juan Nicolás Corzo presented an invention to make the mills move “without the need for water, horses or air”, but it must not have worked because later the liquid continued to be used as a driving force.

So, the water was taken care of and not played with. The efforts to distribute the liquid gave rise to the construction of fountains and water boxes, laying of pipes and the existence of the position of mayor of water, which the members of the council assumed in turn and held annually.

REPUBLIC

During the colonial period, the carnival festivities were known as shrovetide and were celebrated, among other things, with bullfights.

Between 1826 and 1827, an Englishman, Edmond Temple, lived in Potosí, who arrived in the city with the purpose of forming a mining company with the name “Potosi, La Paz and Peruvian Mining Association”.

During his second stay in Potosí he was able to witness the carnival of this city and described it in a book, in English, in which he narrates his trip through South America, “Travels in various part of Peru including a year’s residence in Potosi”.

Nowhere in the description of him, which is in chapter IX of volume II, does it read that he had played with water.

What he describes about the carnival games is this: “I distributed and received, with thoughtless prodigality, showers of flour, powdered starch and chocolates. I threw at the ladies, and was thrown by them, with dozens of eggshells, full of perfumed waters, which are sometimes poured, until drenched, on some favorite victim, and a well-aimed shot in the face with one of those shells. of eggs is not always pleasant; but, since everyone suffers equally, no one can be angered by the joke of a fellow sufferer.” And he adds this sentence: “Nor does it mean insult, when men sympathize” (Page 291).

Therefore, water play, as it is known today, must have begun in periods after 1827, already in the republic, and it is very likely that it was in imitation of what is usually done in places with a tropical climate.

El juego con agua es un elemento reciente en las tradiciones del carnaval potosino

Hasta por lo menos 1827, esa actividad no formaba parte de nuestras carnestolendas.

La gente que cree que el juego con agua forma parte de las tradiciones del carnaval potosino se llevaría una sorpresa si supiera que los documentos y publicaciones prueban que esa actividad fue sumada a estas fiestas recién en tiempos republicanos, así que se puede considerar de incorporación reciente.

La escasez de agua ha determinado que este año se ratifique la prohibición del juego con agua y hasta el gobernador emitió un decreto extendiéndola a todo el territorio departamental. Entre las personas que protestan están quienes dicen que el juego con agua es solo en carnaval, mientras que los ingenios mineros y lavados de autos consumen el líquido todo el año, con poco o ningún control. Otro argumento es que ese juego sería parte de las tradiciones del carnaval y ahí está el error.

Potosí es una ciudad con poca provisión de agua y, por ello, siempre padeció por la escasez de ese líquido. Debido a ello, a nadie se le hubiera ocurrido desperdiciarla mojando a otras personas en carnaval. En los libros de acuerdos del Archivo Secular de Potosí se encuentran varias disposiciones sobre el agua, pero la mayoría de ellas están destinadas a cuidar el líquido, o distribuirlo de mejor manera.

El uso que los ingenios hacían del agua es un problema secular. En un acuerdo del 3 de junio de 1591, por ejemplo, se recomienda que no se les entregue tanta agua. En 1635, Juan Nicolás Corzo presentó un invento para conseguir que los ingenios se muevan “sin necesidad de agua, cabalgaduras ni aire”, pero no debió haber dado resultado pues posteriormente se siguió usando el líquido como fuerza motriz.

Entonces, el agua se cuidaba y no se jugaba con ella. Los esfuerzos para distribuir el líquido dieron lugar a la construcción de fuentes y cajas de agua, tendidos de cañerías y la existencia del cargo de alcalde de aguas, que asumían por turno los integrantes del cabildo y ejercían de manera anual.

REPÚBLICA

Durante la colonia, las fiestas del carnaval eran conocidas como carnestolendas y se festejaban, entre otras cosas, con corridas de toros.

Entre 1826 y 1827 vivió en Potosí un inglés, Edmond Temple, que llegó a la ciudad con el propósito de conformar una empresa minera con el nombre de “Potosi, La Paz and Peruvian Mining Association”.

Durante su segunda permanencia en Potosí pudo presenciar el carnaval de esta ciudad y lo describió en un libro, en inglés, en el que narra su viaje por Sudamérica, “Travels in various part of Peru including a year’s residence in Potosi”.

En ninguna parte de su descripción, que está en el capítulo IX del tomo II, se lee que hubiera juego con agua.

Lo que describe sobre los juegos carnavaleros es esto: “repartí y recibí, con desconsiderada prodigalidad, lluvias de harina, almidón en polvo y bombones. Arrojé a las damas, y fui arrojado por ellas, con docenas de cáscaras de huevo, llenas de aguas perfumadas, que a veces se vierten, hasta empapar, sobre alguna víctima favorita, y un tiro bien dirigido en la cara con uno de esos cascarones de huevos no es siempre agradable; pero, como todos sufren por igual, nadie puede enojarse por la broma de un compañero de sufrimiento”. Y agrega esta sentencia: “Ni tampoco significa insulto, cuando los hombres simpatizan” (Pág. 291).

Por tanto, el juego con agua, como se conoce hoy en día, debió comenzar en periodos posteriores a 1827, ya en la república, y es muy probable que haya sido por imitación del que suele hacerse en lugares con clima tropical.