Con la participación de Summer R. Jackson. Por Michael Blanding, Harvard Business School:

Las observaciones insensibles son comunes en el lugar de trabajo, pero estas “microagresiones” no tienen por qué romper las relaciones. Summer Jackson afirma que quienes manejan los insultos con delicadeza pueden, en realidad, fortalecer los lazos con sus colegas.

Las microagresiones ocurren en el ámbito laboral todo el tiempo: un trabajador blanco puede preguntar a un colega hispano cómo aprendió a hablar tan bien inglés, o un hombre puede referirse de manera casual a las mujeres de la oficina como “chicas”. Pero estas interacciones pueden ser dañinas.

“La persona que dice estas cosas puede que no sepa que hizo algo mal”, señala Summer Jackson, profesora asistente en Harvard Business School. “Pero para quien las recibe, es como un rayo que pone en duda su identidad social, lo hace sentir subordinado y se pregunta: ‘¿Cómo pudo esta persona decirme eso?’”

La persona que dice estas cosas puede que no sepa que hizo algo mal.

Las microagresiones —comentarios aparentemente inocuos hechos por alguien con una identidad social dominante hacia otra persona con una identidad social marginada— resultan insensibles y pueden cortar relaciones si no se abordan adecuadamente. Jackson ofrece consejos sobre cómo reparar el daño en el artículo de Academy of Management Review “It Takes Two to Untangle: Illuminating How and Why Some Workplace Relationships Adapt While Others Deteriorate After a Workplace Microaggression”, escrito junto con Basima Tewfik, del MIT Sloan School of Management.

En un clima laboral donde la retención y la satisfacción están bajo presión, abordar las microagresiones de manera efectiva puede fortalecer la confianza y mejorar el desempeño del equipo, afirma Jackson. Mientras estudios previos se enfocaron en el daño a la cultura organizacional, Jackson y Tewfik plantean un marco para convertir incidentes potencialmente destructivos en oportunidades de fortalecer vínculos.

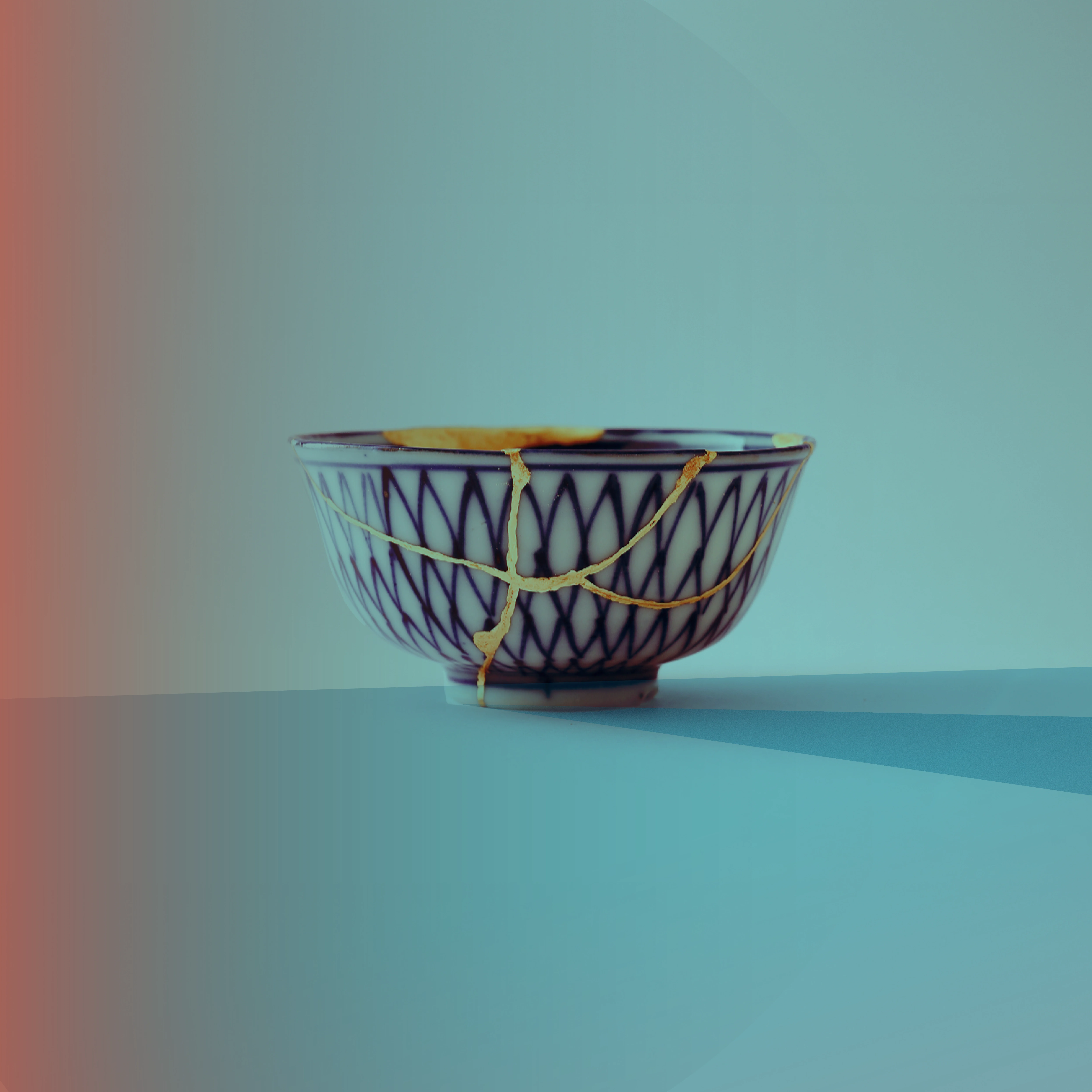

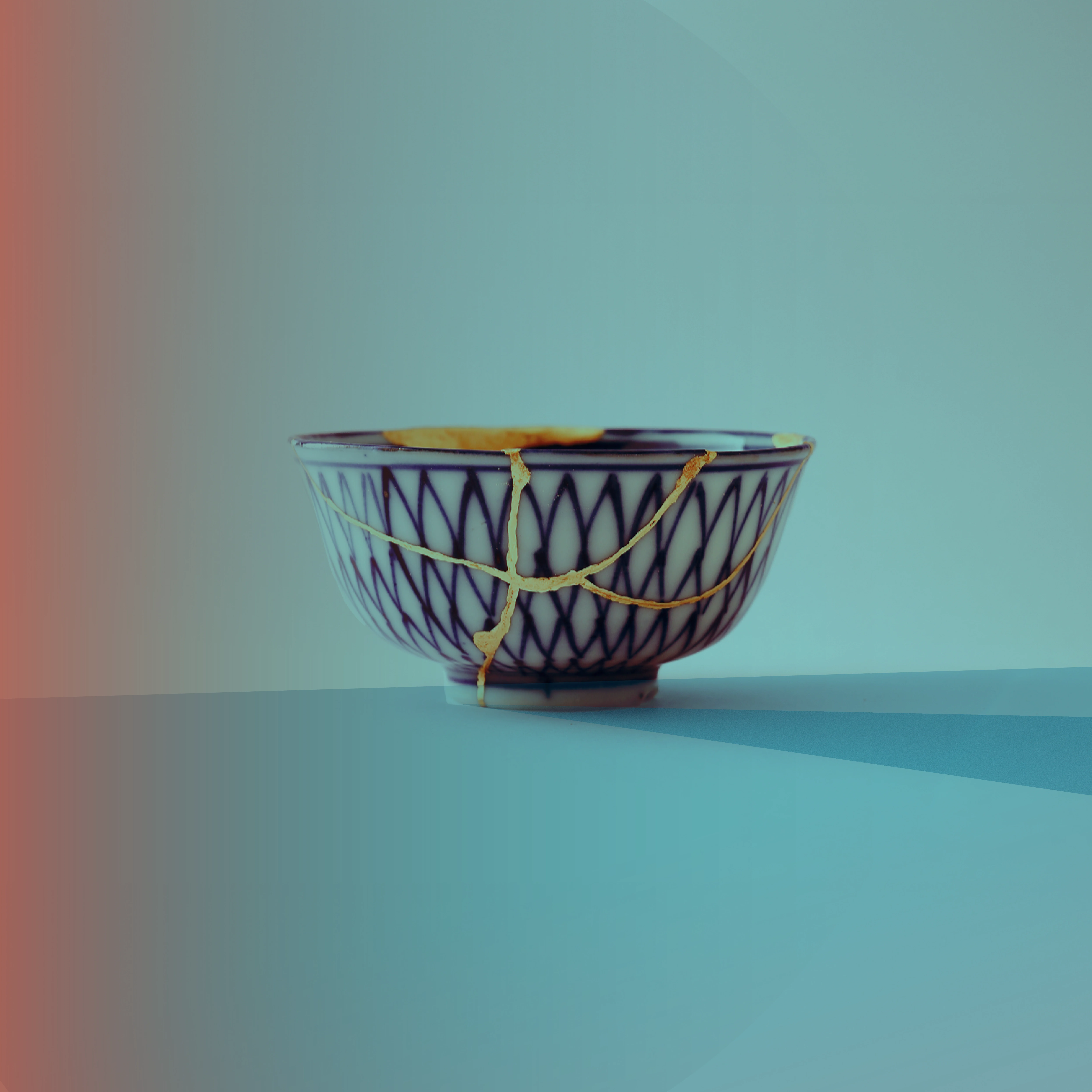

“Queríamos analizar lo que ocurre después de una microagresión y ver si existe una manera de no solo devolver la relación al estado inicial, sino de hacerla más fuerte”, explica Jackson. Al hablar de su investigación, señala que algunos compararon el proceso de sanación descrito en el artículo con el kintsugi, un arte japonés que repara piezas de cerámica rota con laca dorada, haciéndolas incluso más bellas que antes.

Manejando una microagresión

Las microagresiones pueden no ser tan evidentes como una discriminación racial o sexual abierta, pero aún así activan el mecanismo corporal de “lucha o huida”. Si no se enfrentan, las microagresiones repetidas pueden causar estrés crónico, dañar la moral del equipo y llevar a empleados a renunciar.

Sin embargo, estos incidentes no tienen por qué destruir relaciones. Con introspección y comunicación abierta, los colegas pueden superar la ruptura y forjar relaciones más auténticas y de confianza, señalan Jackson y Tewfik.

Como las microagresiones suelen ser involuntarias, la reparación debe empezar por quien las recibe, afirma Jackson. “Hay que salir de la reacción de ‘lucha o huida’ y entrar en la curiosidad. Sí, protégete en el momento, pero luego reflexiona si vale la pena preservar la relación”.

Para ello, recomienda evaluar la relación según estos factores:

- Historia de interacción: ¿Qué tanto se ha visto que la otra persona valora positivamente una cultura de equidad en el trabajo?

- Cercanía relacional: ¿Qué tan conectado se sentía con la otra persona antes del incidente?

- Viabilidad relacional: ¿Qué tan probable es que deba trabajar con esa persona en el futuro?

Responder esas preguntas ayuda a determinar la importancia de reparar la relación y si la persona que cometió la microagresión está dispuesta a abordar el incidente.

“¿Sientes que esta persona genuinamente se preocupa por ti y por tu bienestar?”, plantea Jackson. “Si es así, puedes pasar a una fase de indagación”.

El siguiente paso, añade, es acercarse a la persona con una explicación clara que se centre en el comportamiento y en los sentimientos, sin atacar su carácter. “Podrías decir: ‘Cuando dijiste X, me hizo sentir Y. Y me hizo preguntarme si me ves de la misma forma que a los demás en el equipo’”.

Reparando la relación

Una vez que el receptor comparte honestamente su perspectiva, Jackson dice que corresponde a quien hizo el comentario realizar una introspección similar. Es probable que la persona se sienta incómoda y que su reacción inmediata sea defenderse o justificar su conducta.

“Puede resultar confuso para alguien que no se dio cuenta de cómo se interpretaría su comentario”, señala Jackson. “La mayoría de la gente gusta de pensar que son buenas personas, y eso puede amenazar su autoimagen”.

Sugiere que la persona acusada también intente superar su respuesta inicial de “lucha o huida” y evalúe la cercanía de la relación, reconociendo que el otro no está mencionando el incidente a la ligera. Aunque una disculpa o una aclaración de intención pueden ser útiles, nada sustituye el sincero deseo de comprender.

“Puedes decir: ‘No me di cuenta de que se sintió así. Ayúdame a entender’”, recomienda Jackson.

Lo que pueden hacer los gerentes

Los gerentes también pueden ayudar a sanar relaciones afectadas por microagresiones. A veces, resulta más efectivo evitar la confrontación en el momento y, en cambio, abordar la situación más tarde con curiosidad y deferencia.

“Si tratas de intervenir en el momento, puedes escalar la situación”, afirma Jackson. “En cambio, si hablas después, puedes preguntar: ‘Noté que en la reunión reaccionaste al comportamiento de tal persona. ¿Qué pasó y cómo puedo ayudar?’”

Aunque estas conversaciones no son fáciles, pueden abrir camino a una restauración de relaciones y hasta liberar apertura, creatividad y colaboración, asegura Jackson.

“Cuando las personas sienten que pueden llevar su ser completo al trabajo, experimentan un mayor sentido de pertenencia y de conexión con la organización”, señala. “Ya no se trata de un ‘choque de realidades’, sino de realmente comprender y aceptar las realidades de los demás a un nivel más profundo”.

Cuando las personas sienten que pueden llevar su ser completo al trabajo, experimentan un mayor sentido de pertenencia y de conexión con la organización.

Pese a las mejores intenciones, advierte que es poco realista esperar que las microagresiones no ocurran en el trabajo. Los puntos ciegos culturales y las creencias implícitas inevitablemente hacen que la gente diga cosas ofensivas sin querer.

“Es muy difícil saber qué aspectos de la identidad social de alguien serán relevantes para ellos y todos los estereotipos históricos que podrían estar asociados”, dice Jackson. En lugar de enfocarse en la prevención, recomienda que los gerentes prioricen la normalización de conversaciones abiertas y la reparación de relaciones.

“Es una verdadera oportunidad para aprender algo nuevo sobre otra persona e incorporar ese entendimiento en tu propia capacidad de ser un mejor colega”, concluye Jackson.

Imagen de Ariana Cohen-Halberstam con recurso de AdobeStock/Marco Montalti

Featuring Summer R. Jackson. By Michael Blanding, Harvard Business School:

Insensitive remarks are common in the workplace, but these “microaggressions” don’t have to break relationships. Summer Jackson says people who handle insults delicately can actually strengthen connections with colleagues.

Microaggressions happen in the workplace all the time: A White worker might ask a Hispanic colleague how they learned to speak English so well, or a man might casually refer to women in the office as “girls.” But these interactions can be damaging.

“The person saying these things might not know they’ve done anything wrong,” says Summer Jackson, an assistant professor at Harvard Business School. “But for the recipient, it’s like a lightning bolt that calls into question their social identity, makes them feel subordinate, and makes them wonder, ‘How could this person say this to me?’”

The person saying these things might not know they’ve done anything wrong.

Microaggressions—which are seemingly innocuous statements made by a person holding a dominant social identity toward another person with a marginalized social identity—come across as insensitive and can sever relationships if they’re not properly addressed. Jackson provides advice for how to repair the damage in the Academy of Management Review article “It Takes Two to Untangle: Illuminating How and Why Some Workplace Relationships Adapt While Others Deteriorate After a Workplace Microaggression,” coauthored with Basima Tewfik of the MIT Sloan School of Management.

In a workplace climate where retention and job satisfaction are under pressure, addressing microaggressions effectively can strengthen trust and improve team performance, Jackson says. While previous studies of microaggressions have focused on the damage to workplace culture, Jackson and Tewfik offer a framework for turning potentially destructive incidents into opportunities to form stronger connections.

“We wanted to unpack what happens after a microaggression and see if there’s a way people can get to a place of not just bringing the relationship back to the status quo, but make it stronger,” Jackson says. When discussing her research, Jackson notes that others have drawn comparisons between the healing process outlined in the paper and kintsugi, a Japanese art form that repairs broken pottery with a golden lacquer, making it even more beautiful than before.

Handling a microaggression

Microaggressions may not be as overt as more blatant racial or sexual discrimination, but they can still kick off the body’s “fight or flight” mechanism. Left unaddressed, repeated microaggressions can cause chronic stress, hurt team morale, and push employees to quit.

However, these incidents don’t have to destroy relationships. With introspection and open communication, colleagues can mend the rift and forge more authentic and trusting relationships, say Jackson and Tewfik.

Since microaggressions are often unintentional, repair must start with the recipient, says Jackson. “You have to move out of the ‘fight or flight’ reaction into curiosity,” Jackson says. “Yes, protect yourself in the moment, but then reflect on whether the relationship is worth preserving.”

To do that, she says, recipients of microaggressions should evaluate the relationship based on these factors:

- Interaction history. How much have they seen the other person positively value an equitable culture in the workplace?

- Relational closeness. How close and connected did they feel toward the other person before the incident?

- Relational viability. How likely are they to work with this person in the future?

Answering those questions can help the recipient assess the importance of repairing the relationship and determine whether the person who made the microaggression is willing to address the incident.

“Do you feel like this is someone who genuinely cares about you and your well-being?” Jackson asks. “If so, you can start to move into an inquiry phase.”

The next step, she says, is approaching the person with a clear explanation that focuses on the behavior and feelings, rather than attacking the person’s character. “You might say, ‘When you said X, it made me feel Y. And it made me wonder if you see me the same way you see others on the team.’”

Repairing the relationship

Once the recipient honestly shares their perspective, Jackson says, it’s up to the person who made the remark to go through similar introspection. After all, the person is likely to feel uncomfortable, and the knee-jerk reaction may be to defend or justify the behavior.

“It can be confusing to someone who may not realize how their comment would be interpreted,” Jackson says. “Most people like to think they are good people, and so it can cause a threat to someone’s self-image.”

She suggests that the person accused of the microaggression also try to move past their initial “fight or flight” response and similarly evaluate the closeness of the relationship, realizing that the other person isn’t raising the incident flippantly. While an apology or reassurance of intent can be helpful, that’s not nearly as powerful as a sincere desire to understand.

“You can say, ‘I didn’t realize it landed that way. Help me understand,’” Jackson says.

What managers can do

Managers can also help heal workplace relationships suffering from microaggressions. Sometimes, it’s effective to avoid confrontation in the moment and instead approach the situation later with curiosity and deference.

“If you try to intervene in the moment, it can escalate the situation,” Jackson says. “Whereas if you meet the person later, you can ask, ‘I noticed in the meeting that you reacted to so-and-so’s behavior. What was going on then, and how can I help?’”

While such conversations aren’t easy, they can lead to breakthroughs in restoring and transforming relationships, Jackson says, and even unleash openness, creativity, and collaboration.

“When people feel like they can bring their whole selves to work, they have a better sense of belonging and connectivity to the organization,” she says. “It’s no longer a ‘clash of realities,’ but you actually come to see one another’s realities better and accept one another on a deeper level.”

When people feel like they can bring their whole selves to work, they have a better sense of belonging and connectivity to the organization.

Despite people’s best intentions, she notes, it’s unrealistic to expect that microaggressions won’t happen at work. Cultural blind spots and implicit beliefs inevitably cause people to unwittingly say offensive things to others.

“It’s really hard to know how people’s social identities are going to be salient to them and all the different historical stereotypes that might be associated with them,” Jackson says. Instead of emphasizing prevention, she recommends that managers focus on normalizing open conversations and repairing relationships.

“It’s a real opportunity to learn something new about another person and incorporate that understanding into your own ability to be a better colleague,” Jackson says.

Image by Ariana Cohen-Halberstam with asset from AdobeStock/Marco Montalti