By Raúl Rivero Adriázola, Brújula Digital:

An Irishman, Bolivia’s First Envoy to Its Pacific Coast

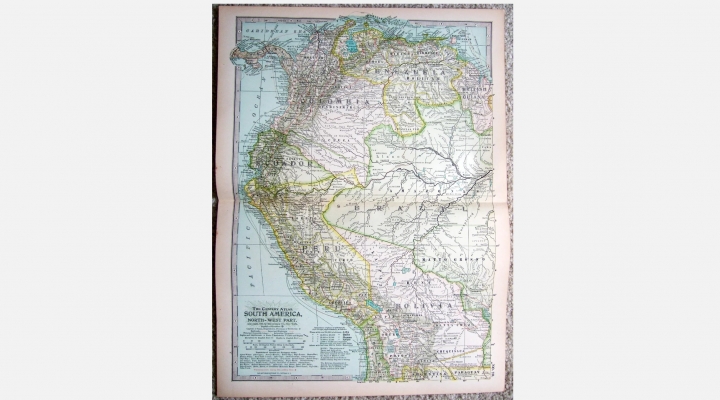

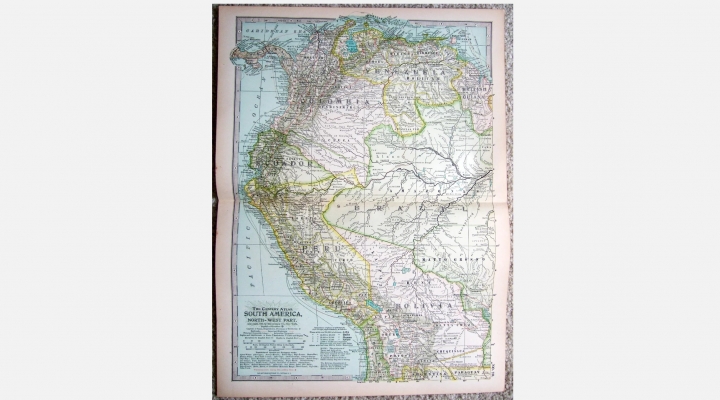

At the beginning of the Republic, Marshal Antonio José de Sucre, acting as interim president until the arrival of Liberator Bolívar to the new homeland, agreed with him that one of the most urgent tasks to be undertaken was consolidating Bolivia’s sovereignty over its geographical space, based on the territorial foundation of the extinct Audiencia de Charcas. Thus, he prioritized securing recognition of its maritime coastline and establishing and constructing a port in Atacama, a territory that had previously been politically dependent on that Audiencia and ecclesiastically under the jurisdiction of the Bishopric of Potosí.

In early November 1825, Francisco Burdett O’Connor, who was in the province of Tarija, having just helped incorporate it into Bolivia, received the following message from the Marshal of Ayacucho: “To Colonel and Chief of the General Staff, Francisco Burdett O’Connor: Sir, His Excellency the Liberator has seen fit to entrust you with a mission of utmost importance, which, if successfully accomplished, will earn you not only honor but also the gratitude of all the peoples of Upper Peru (…). As this new Republic lacks an operational seaport, proceed to the coast of Atacama, map the Loa, Cobija, Mejillones, and Paposo, and open for trade the one best suited for the purpose.”

A few days later, following these instructions, O’Connor set out for Tupiza, accompanied by his aide, Tarija-born cadet Matilde Rojas, and a Colombian servant who had been with him for several years. After securing supplies there, they headed south, entering Atacama through the Calahoyo ravine to the Santa Rosa mine, at the foot of the Licancabur volcano. After resting and finding a guide named Fermín Torres, they set off for Atacama. To endure the arduous journey across the barren land to the coast, O’Connor hired a group of mule drivers with their animals. After passing through Chacance and Culupu, suffering from a severe lack of water for both themselves and their animals, O’Connor arrived in Cobija on December 8, where he encountered only one resident—a man from Cochabamba named Maldonado. He informed him that all his workers, who had been engaged in fishing, had perished due to a smallpox epidemic, leaving only himself and his brother as survivors.

The following day, on the first anniversary of the Battle of Ayacucho—where Francisco Burdett O’Connor had played a prominent role as Chief of Staff of the Liberating Army—the Colombian war brig Chimborazo arrived at Cobija. It was commanded by Commodore Carlos Wright, head of the Colombian naval squadron in the Pacific, who carried Bolívar’s order to take O’Connor on a reconnaissance of all the ports listed in Sucre’s instructions.

In his Memoirs, written in the late 1860s—almost 35 years after this expedition and a decade before the War of the Pacific—the former Irish officer summarized his journey along Bolivia’s Pacific coastline as follows: “The next day, we set out to survey all the ports mentioned in my instructions. We found that Cobija had the best anchorage and the most convenient port, though it lacked water, but this issue could be addressed. I parted ways with the Commodore at the port of Loa, which is merely a roadstead, with water from the Loa River so salty it is undrinkable. The port of Mejillones is beautiful but has no water. Paposo has a river with fish that swim into it, but the land route from Paposo to Atacama has neither a drop of water nor any pasture, making it impracticable. However, had I been able to act in the future, I would have enabled both ports, Paposo and Atacama—the first as a storage point for unloading goods and the second as a departure point to Potosí, arranging for bales and other cargo to be transported from one location to the other by boats, which could be brought to shore without any risk. This would have prevented Chile’s later unfounded claims.”

The Chimborazo left O’Connor at the port of Quillagua, where he dedicated himself to drafting his mission report and the first maps of Bolivia’s coastal territories, using as a reference the Royal Orders issued by the Spanish Crown that had established the boundaries of this territory under the jurisdiction of the Audiencia de Charcas. Once this task was completed, he decided to travel from the coast to Potosí, accompanied by his guide and mule drivers, seeking the best route for the establishment of postal relay stations, corrals, and pastures. The journey was extremely harsh, with the travelers going days without finding water or grass for their horses. Nevertheless, though exhausted, they arrived safely in Potosí.

A few days later, O’Connor proceeded to Chuquisaca to report his arduous mission to Sucre, presenting him with the report, maps, and other notes concerning Upper Peru’s territorial demarcation. The next day, the Marshal summoned him to say that he had carefully examined the maps and data collected during the mission and was very satisfied.

On December 26, 1825, the Bolivian government issued a decree stating that “the port of Cobija is designated as the Republic’s main port, as Puerto La Mar.” Unfortunately, due to the lack of dredging of its coast and the absence of infrastructure for proper operation, this port had a precarious existence.

Later, O’Connor lamented that Sucre made little use of his mission’s findings, concluding that it was due to the government’s financial constraints, which prevented sufficient resources from being allocated to make Puerto La Mar-Cobija fully operational. The lack of infrastructure and properly maintained postal relay stations meant Bolivia remained reliant on foreign ports, which were more accessible at the time. For this reason, Sucre later approached Peruvian President Andrés de Santa Cruz, proposing a land swap: the port of Arica in exchange for Copacabana on Lake Titicaca—an offer that was rejected.

Looking back today at the events that unfolded and ultimately led to our nation’s landlocked condition, had Sucre been more determined in following O’Connor’s advice and establishing genuine sovereignty over that territory by developing one or more functional ports, or had Santa Cruz accepted the proposed exchange of Copacabana for Arica—Upper Peru’s natural port—the history of our access to the sea might have been written very differently.

Raúl Rivero is an economist and writer.

Por Raúl Rivero Adriázola, Brújula Digital:

Un irlandés, el primer enviado de Bolivia a su costa del Pacífico

A inicios de la República, el mariscal Antonio José de Sucre, presidente interino hasta el arribo a la nueva patria del Libertador Bolívar, estableció de común acuerdo con él que una de las más urgentes tareas a llevar adelante era la de consolidar la soberanía de Bolivia sobre su espacio geográfico, partiendo de la base territorial de la extinta Audiencia de Charcas. Es así que definió como aspecto prioritario apurar el reconocimiento de su costa marítima y la creación y construcción de un puerto en Atacama, territorio antes dependiente políticamente de esa Audiencia y eclesiásticamente del obispado de Potosí. A principios de noviembre de 1825, Francisco Burdett O’Connor, que se encontraba en la provincia de Tarija, a la que recién había ayudado a incorporarse a Bolivia, recibió el siguiente mensaje del Mariscal de Ayacucho: “Al señor Coronel Jefe de Estado Mayor General, Francisco Burdett O’Connor.- Señor: Su excelencia el Libertador ha tenido a bien conferir a Usía una misión de suma importancia, la cual, verificada con buen suceso, le granjeará no sólo la honra, sino la gratitud de todos los pueblos del Alto Perú (…). Al carecer esta nueva República de un puerto de mar en operaciones, diríjase a la costa de Atacama, levante mapas del Loa, Cobija, Mejillones y Paposo, y habilite para el comercio el que encontrase mejor”.

Pocos días después, y en cumplimiento de esa instrucción, O’Connor salió rumbo a Tupiza, en compañía de su ayudante, el cadete tarijeño Matilde Rojas, y un sirviente colombiano que lo acompañaba hace varios años. Habiéndose aprovisionado en esa población, partieron rumbo al sud, para entrar a Atacama por la quebrada de Calahoyo hasta la mina Santa Rosa, al pie del volcán Licancabur. Luego de descansar y conseguir un guía, de nombre Fermín Torres, se dirigieron a Atacama. Con el fin de soportar el cruce por el árido territorio hasta la costa, el enviado contrató a un grupo de arrieros con sus mulas. Tras atravesar Chacance y Culupu y sufrir por la falta de abrevaderos tanto para él, su guía, sus arrieros y animales, O’Connor arribó a Cobija el 8 de diciembre y se encontró con solo habitante, un cochabambino de apellido Maldonado, quien le contó que todos sus trabajadores, dedicados a la pesca, habían muerto a consecuencia de una epidemia de viruela, quedando como sobrevivientes únicamente él y su hermano.

Al día siguiente, fecha del primer aniversario de la batalla de Ayacucho, donde Francisco Burnett O’Connor, tuvo destacada actuación como jefe de estado mayor del Ejército libertador, llegó al puerto de Cobija el bergantín de guerra colombiano “Chimborazo”, al mando del jefe de la escuadra naval colombiana en el Pacífico, comodoro Carlos Wright, con la orden del Libertador de llevar a O’Connor a reconocer todos los puertos que tenía anotados en las instrucciones enviadas por Sucre.

En sus Memorias –escritas a fines de la década de 1860, o sea casi 35 años después de ese viaje y 10 antes de la Guerra del Pacífico–, el antiguo oficial irlandés resume así su aventura por la costa boliviana en el Pacífico: “Al día siguiente emprendimos el reconocimiento de todos los puertos mencionados en mis instrucciones, y hallamos que el de Cobija tenía el mejor fondo para ancla y el puerto más cómodo también, aunque escaso de agua, pero de poder aumentar la cantidad. Me separé del Comodoro en el puerto de Loa, que no es más que una rada, y con el agua del río Loa tan salada que no se puede beber. El puerto de Mejillones es hermoso, pero carece de agua. El Paposo tiene río con pescado que le entra, pero el tránsito desde Paposo por tierra a Atacama no tiene una gota de agua, ni pasto, y por estas razones inverificable. Empero, si yo hubiese podido penetrar en lo futuro, hubiese habilitado los dos puertos, el de Paposo y el de Atacama; el primero con almacenes para el desembarco de mercancías, y el segundo para punto de partida desde Potosí, disponiendo que los fardos y demás cargas se transportasen de un punto al otro en lanchas, arrimándolas a la costa sin peligro alguno. De este modo se hubiesen evitado las posteriores pretensiones infundadas de Chile”.

El “Chimborazo” deja a O´Connor en el puerto de Quillagua. En este pueblo se dedica a elaborar el informe de su misión y los primeros mapas de los territorios costeros de Bolivia, tomando como referencia las Reales Órdenes emitidas por la corona española, que establecían los límites de este territorio en posesión de la Audiencia de Charcas. Terminada esa tarea, decide dirigirse de la costa a Potosí, en compañía del guía y arrieros, buscando la mejor ruta para el levantamiento de casas de posta, corrales y potreros. La ruta tomada por los viajeros fue tremendamente hostil, pues por varias jornadas les resultó imposible conseguir agua ni pasto para los caballos; sin embargo, aunque exhaustos, arribaron sanos a Potosí.

Pocos días después O’Connor se dirige a Chuquisaca y se presenta ante Sucre, a fin de dar parte de su ardua misión, entregándole el informe, los mapas y otros apuntes relativos a las demarcaciones del Alto Perú. Al día siguiente, el Mariscal lo llama para indicarle que había examinado con atención los mapas y los datos tomados en el curso de su misión y que estaba muy satisfecho.

El 26 de diciembre de 1825, el gobierno boliviano emite un decreto, por el que “queda habilitado como puerto mayor de la República, como Puerto La Mar, el de Cobija”. Lamentablemente, al no haberse dragado su costa y no dotarle de infraestructura para operar adecuadamente, este puerto tuvo vida precaria.

Posteriormente, O’Connor se lamenta de que Sucre haya hecho poco uso de los resultados de su misión, llegando a la conclusión de que se debió a las apreturas económicas del erario público, que impedían tener recursos suficientes para habilitar el puerto de La Mar-Cobija y la ruta de postas en condiciones adecuadas para operar todo el año y con barcos de pequeño y mediano calado, a fin de dejar de usar puertos ajenos, hasta ese momento más accesibles. Fue por esa razón, entonces, que Sucre se dirigió tiempo después al presidente de Perú, Andrés de Santa Cruz, proponiéndole el trueque del puerto de Arica por el de Copacabana –en el lago Titicaca, oferta que fue rechazada.

Hoy día, viendo a la distancia los hechos que se sucedieron y que llevaron a nuestro país a su enclaustramiento, si Sucre se hubiera empeñado en seguir los consejos de O’Connor y sentado bases reales de soberanía sobre ese territorio, al habilitar uno o más puertos operables, o si Santa Cruz aceptaba la propuesta de trueque de Copacabana por Arica, puerto natural del Alto Perú, seguramente la historia de nuestro acceso al litoral se hubiera escrito de diferente manera.

Raul Rivero es economista y escritor.