By Jose Toro Montoya, Vision 360:

What happened after the mutiny?

Sucre was in Gamarra’s hands until the signing of the Piquiza agreement or settlement, according to 19th-century publications that present a disturbing version.

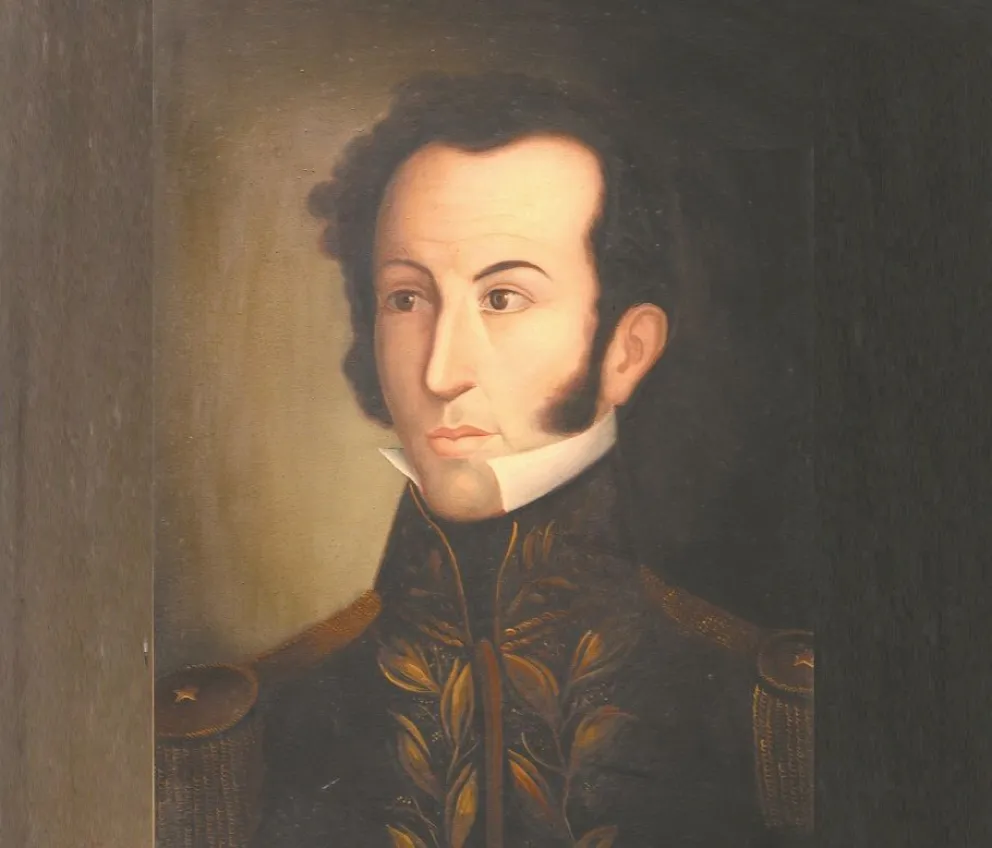

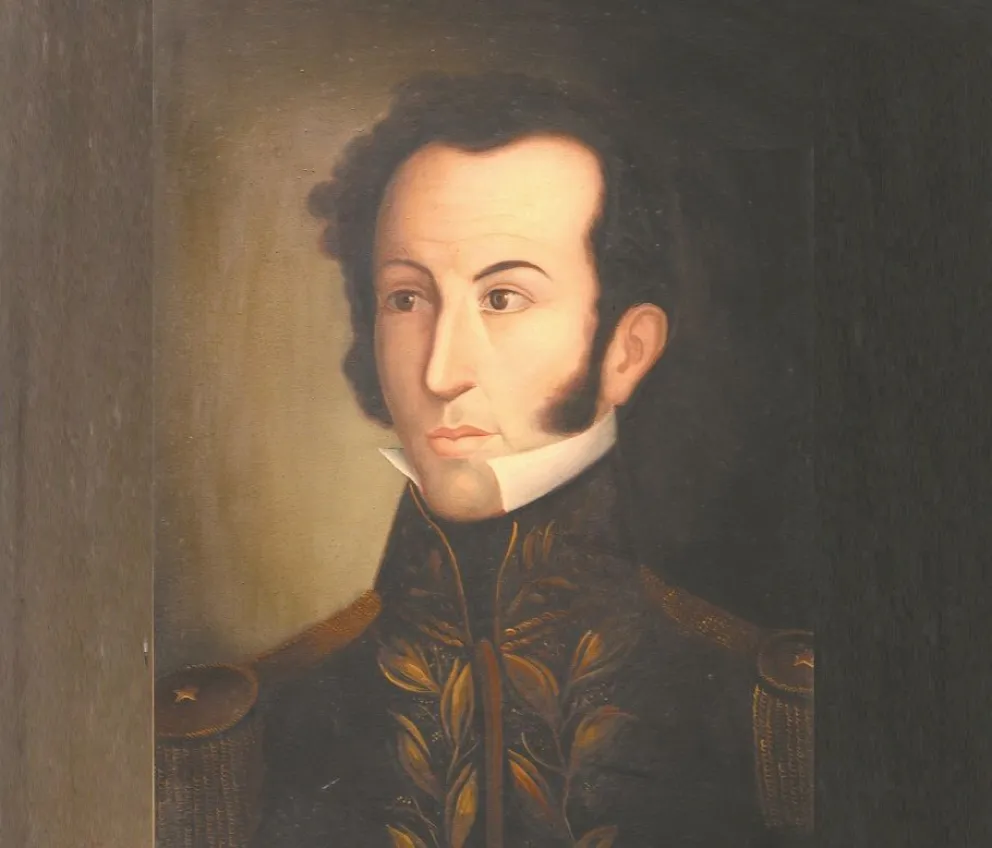

The government of Antonio José de Sucre began to fall on April 18, 1828, when a mutiny occurred in Chuquisaca, during which he was wounded in the arm. This event coincided with the first Peruvian invasion, led by Agustín Gamarra, but there is little or nothing about it in history books. What is known is that the Marshal of Ayacucho recovered from his injuries in Ñucchu, and from there, there is a time gap until he presented his resignation and delivered his famous message to the Nation in August. What happened during those nearly four months? Nineteenth-century publications present a disturbing version: Sucre was kidnapped and in Gamarra’s hands until the signing of the Piquiza agreement or settlement.

It is striking that historians have not paid attention to the gaps that can be clearly seen in the chronology of events. If the agreement or settlement was signed on July 6, 1828, what happened between Ñucchu and Piquiza? Why is there practically nothing about what happened for at least two months? And the most obvious question: if the mutiny occurred in Chuquisaca, now Sucre, why was the treaty signed in such a remote place as Piquiza, which even today is nothing more than a remote hamlet on the interdepartmental border between Potosí and La Paz?

Graphics: SIHP

The data began to emerge from the discovery of a photostatic copy of the “Copiador de la correspondencia oficial del Jefe del estado Mayor General León Galindo. — 32 págs. — Puna — Potosí – 1828” (BC UMSA Mss. 542). What did Puna have to do with this story? Due to the seals, it was not difficult to locate the original in the Historical Archive of the Central Library of the UMSA: it is the correspondence between Galindo; the prefect of Potosí, Francisco López; and the governors of cantons such as Chaquí, Quivincha, Siporo, Miculpaya, Esquiri, Caiza, Toropalca, and Vilcaya as part of a military campaign: the defense of Bolivia against the Peruvian invasion led by Agustín Gamarra.

To understand what had happened, it must be remembered that, at the end of December 1827, Galindo had left the Prefecture of Potosí to Francisco López and went to La Paz as Chief of Staff, a position he was holding on April 18, 1828.

After the outbreak of the mutiny, López left Potosí to address it, while Galindo mobilized from La Paz. According to what was known and confirmed by documents, the Chief of Staff—who logically had troops under his command—did not go to Chuquisaca, nor is there any record of his presence there after the events of April 18. Why?

The gaps were created by the existence of at least two different narratives about those events: on one hand, there were Sucre and his supporters, that is, the legally constituted government, which described the events as an invasion, with all that this implies. On the other hand, there were the rebels who viewed the April 1828 events as a revolution aimed at freeing Bolivia from Colombian occupation, of which Sucre was considered the main leader. Casimiro Olañeta was part of this latter trend and did everything in his power to impose this version.

In 1877, Gabriel René Moreno published his “Documents on the First Assault of Militarism in Bolivia,” not in Bolivia, but in Chile, noting that “the crime of April 18 remains shrouded in shadows for posterity. In Bolivia itself, it is known only vaguely; because even the vague details of the event were all that could be gleaned from contemporary official documents…” (BNCH MC0049069, 247).

It was not a simple article but was accompanied by transcripts of documents revealing several things, from one that discussed the solidarity shown by Tomás Frías and doña Josefa de Lizarazu with the illustrious injured (Ídem, 260), to the still-debated claim that Sucre was kidnapped in Ñucchu and remained in that condition until the signing of the Piquiza treaty.

How did this happen? Behind the conspiracy was Gamarra, who already had an army of 6,000 men in Puno six months before the events of April in Chuquisaca (Ídem, 269). Twelve days after the mutiny, Gamarra invaded Bolivia (Ídem, 271) and went as far as Oruro, continuing on to Potosí, but established his camp in Siporo, today the Cornelio Saavedra province.

Meanwhile, according to this version, Colonel Pedro Blanco defected from the Bolivian army and met with Gamarra in Macha:

“Colonel Blanco came from Chichas, both to escape a major force that had left in pursuit from Potosí, and with the intention of joining Gamarra, who was already in Macha. He passed by the outskirts of the city (Potosí) without entering it, being guarded by a small infantry force. After about 20 days, he returned with an additional squadron of Peruvians, with Peruvian banners; they immediately went to Ñuccho and took the Great Marshal prisoner to Gamarra’s camp (in Siporo)” (MALLO, 1877: 272).

This testimony is reinforced by a publication from the time:

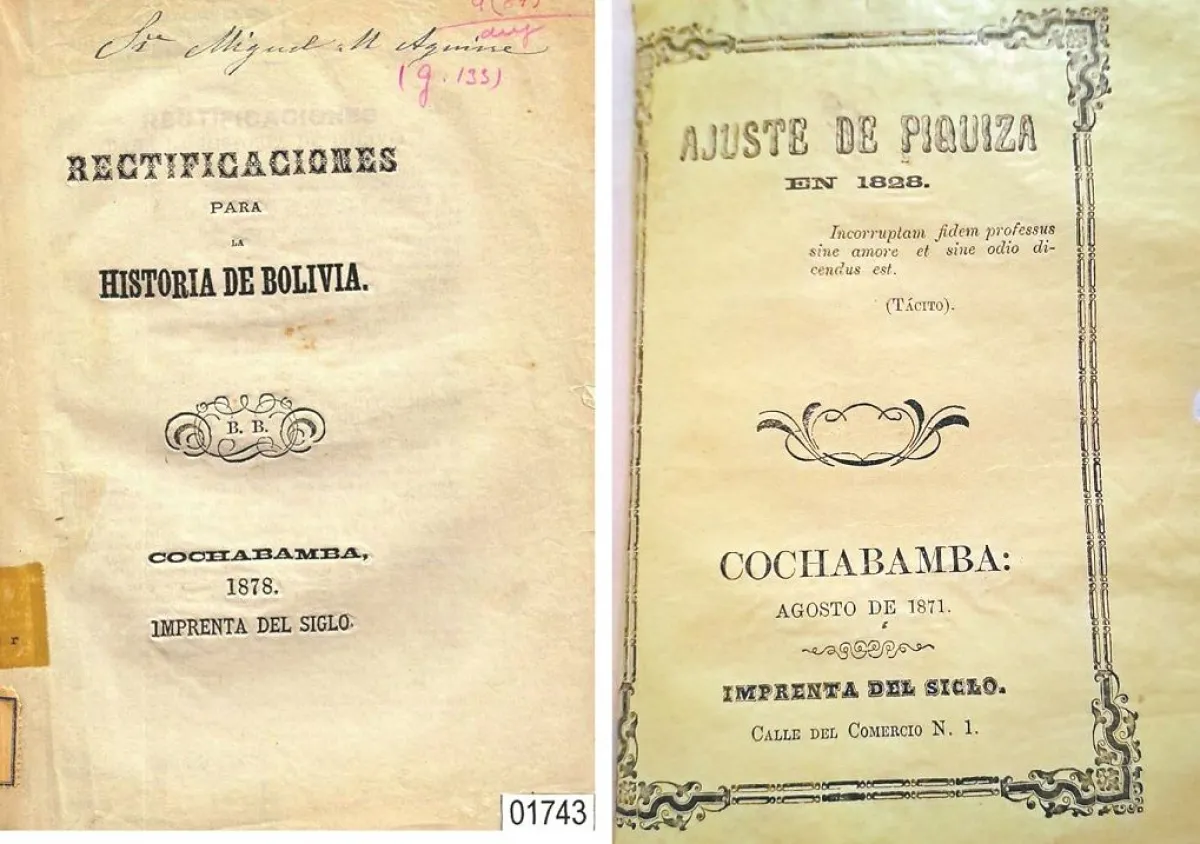

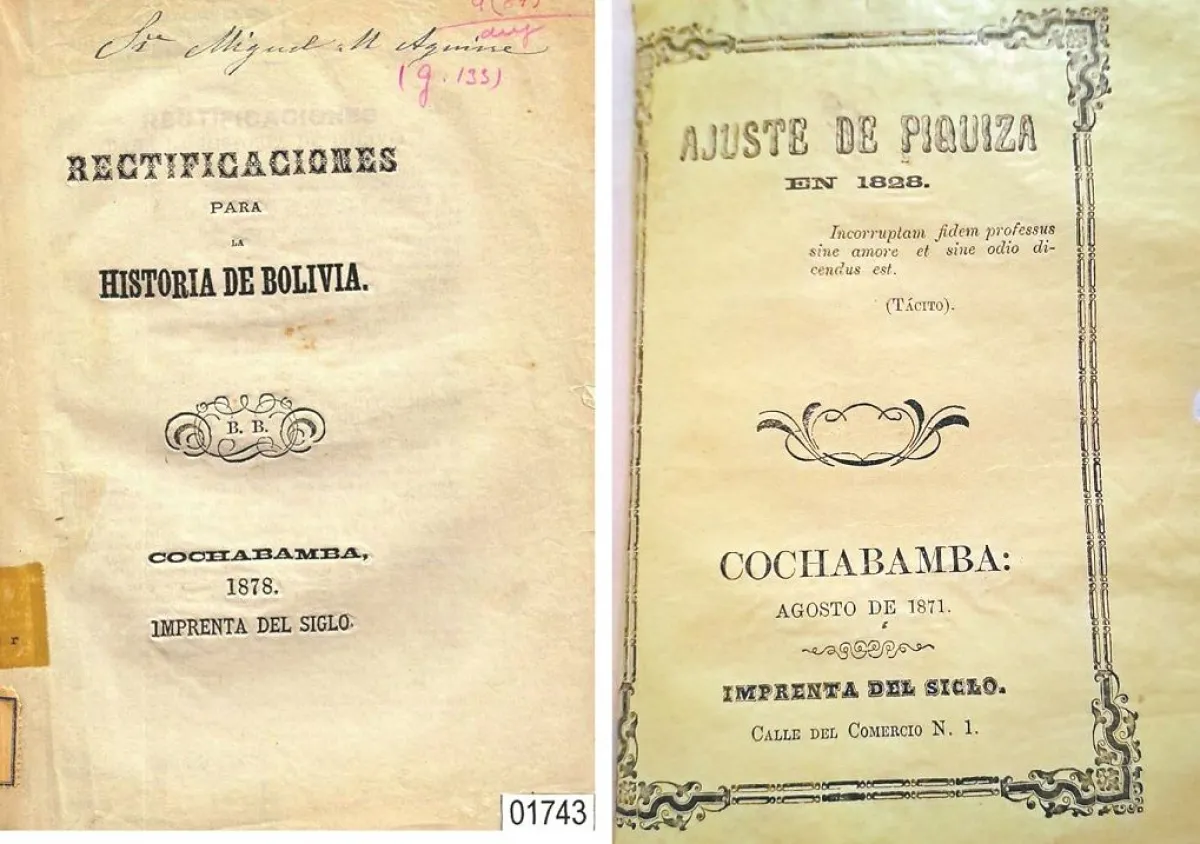

“Colonel Blanco, according to the gentleman, at the beginning of May, having departed from Cotagaita, headed to Chuquisaca. He captured the Great Marshal President in Ñuccho, where he was being treated; he continued his march to Macha. There he received reinforcements with a squadron of Peruvians. He returned towards Potosí, and was in Puna during the Piquiza conferences, still holding his prisoner” (AGUIRRE, 1871: 5).

Through a 50-page publication, Pedro Blanco’s children, Cleómedes and Federico, refuted Moreno’s publication and, despite the evidence presented, rejected the version that their father had taken Sucre prisoner to hold him for two months. “The movement of April 18, 1828, was a great and true revolution” (BC-F-01743, 1878: 2), they published.

The Blancos point out that there is evidence Sucre prepared his message to the nation in Chuquisaca, and in this message he says, “I was abruptly torn away, on July 4, from the retreat where I was recovering my wounds” (Ídem, 15). Additionally, a publication from El Cóndor de Bolivia states, “The President of the Republic left on the first of the current month for a country house five leagues from this capital. His friends will be pleased to know that he is recovering. On the eleventh, the fourteenth splinter of bone was removed from his arm, and the surgeons still believe there may be one more. However, they think the wounds will heal within a month” (CÓNDOR, 1828: 2).

The controversy lasted until 2024, when a copy of Galindo’s correspondence was found in the archive, library, and museum in Colcapirhua, Cochabamba, curated by his descendant Arturo Galindo Grandchandt. These letters show that at least between June 17 and July 5, 1828, there was intense troop movement in Bartolo (now Betanzos) and Chaquí, which are close to Siporo, as well as in Puna and Potosí.

The date of June 17 corresponds to the first letter found in the folder preserved at UMSA, as the letters are numbered, and the one appearing first is number 323, suggesting that 321 might be missing.

The content describes troop deployments in the mentioned locations, as well as the recruitment of volunteers, assignment of uniforms, and other movements typical in wartime. There are explicit references to Pedro Blanco, considering him responsible for the April 18, 1828, mutiny and therefore a target to be eliminated. In other words, these documents support the version that Sucre was kidnapped in Ñucchu and taken to Siporo, where the Piquiza treaty was signed on July 6, 1828. It is worth noting that Piquiza is very close to Siporo. If Antonio José de Sucre was held in that location, it seems to explain why Piquiza was chosen as the place for signing the treaty.

Now, if Sucre was kidnapped in Siporo, it justifies the presence of the Chief of Staff, León Galindo, with his troops in the area. That is where he executed the resistance to the first Peruvian invasion. For reasons that still need to be studied, Gamarra was unable to complete the occupation of the invaded territory and ended up signing the Piquiza treaty, which was ultimately humiliating for Bolivia. Knowing this, leading his troops, Galindo chose to head towards Salta, arriving there on July 24, 1828.

(*) Juan José Toro is a founder and member of the Society of Historical Research of Potosí (SIHP).

Graphics: Courtesy of SIHP

References:

- AGUIRRE, Miguel María. 1871. Ajuste de Piquiza en 1828. Imprenta del Siglo. Cochabamba.

- BC-F-01743, Biblioteca Central de la UMSA. BLANCO, Federico y Cleómedes. Rectificaciones para la historia de Bolivia. Imprenta del Siglo. Cochabamba.

- BNCH MC0049069. MORENO del Rivero, Gabriel René. “Documentos sobre el primer atentado del militarismo en Bolivia”. En Revista Chilena. Tomo IX. Jacinto Núñez, editor. Imprenta de la República. Santiago. 1877. pp. 246-288.

- MALLO, Jorge. “Apuntes sobre la connivencia del general Blanco y los demás incidentes al mismo respecto”. En BNCH MC0049069.

Por Jose Toro Montoya, Vision 360:

¿Qué pasó tras el motín?

Sucre estuvo en manos de Gamarra hasta la firma del acuerdo o ajuste de Piquiza, según publicaciones del siglo XIX que presentan una inquietante versión.

El gobierno de Antonio José de Sucre comenzó a caerse el 18 de abril de 1828, cuando se produjo un motín en Chuquisaca en el que resultó herido en el brazo. Este hecho coincidió con la primera invasión peruana, liderada por Agustín Gamarra, pero poco o nada hay sobre ella en los libros de historia. Lo que se sabe es que el Mariscal de Ayacucho se restableció de sus heridas en Ñucchu y, a partir de ahí, hay un salto temporal hasta que presentó su renuncia y emitió su famoso mensaje a la Nación, en agosto. ¿Qué sucedió durante casi cuatro meses? Publicaciones del siglo XIX presentan una inquietante versión: Sucre estuvo secuestrado y en manos de Gamarra hasta la firma del acuerdo o ajuste de Piquiza.

Llama la atención que los historiadores no hayan reparado en los vacíos que se puede advertir con claridad en la cronología de los hechos. Si el acuerdo, o ajuste, fue firmado el 6 de julio de 1828, ¿qué pasó entre Ñucchu y Piquiza? ¿Por qué hay prácticamente nada de lo sucedido durante por lo menos dos meses? Y, la pregunta más obvia: si el motín ocurrió en Chuquisaca, hoy Sucre, ¿por qué se firma el tratado en un lugar tan remoto como Piquiza que, aun hoy, no es más que un remoto caserío en el límite interdepartamental entre Potosí y La Paz?

Los datos comenzaron a surgir a partir del hallazgo de la copia fotostática del “Copiador de la correspondencia oficial del Jefe del estado Mayor General León Galindo. — 32 págs. — Puna — Potosí – 1828” (BC UMSA Mss. 542). ¿Qué tenía que ver Puna en esta historia? Por los sellos, no fue difícil ubicar el original en el Archivo Histórico de la Biblioteca Central de la UMSA: se trata de la correspondencia entre Galindo; el prefecto de Potosí, Francisco López; y los gobernadores de cantones como Chaquí, Quivincha, Siporo, Miculpaya, Esquiri, Caiza, Toropalca y Vilcaya como parte de una campaña militar: la defensa de Bolivia frente a la invasión peruana encabezada por Agustín Gamarra.

Para entender lo que había sucedido, hay que recordar que, a fines de diciembre de 1827, Galindo había dejado la Prefectura de Potosí a Francisco López y se fue a La Paz como Jefe de Estado Mayor, cargo que estaba desempeñando al 18 de abril de 1828.

Tras el estallido del motín, López salió de Potosí para mitigarlo mientras que Galindo se movilizó desde La Paz. Por todo lo que se sabía, y los documentos confirman, el Jefe de Estado Mayor —que, lógicamente, tenía tropas a su mando— no se dirigió a Chuquisaca ni hay registro de que haya estado ahí después de los hechos del 18 de abril. ¿Por qué?

Los vacíos fueron creados por la existencia de por lo menos dos narrativas diferentes acerca de esos sucesos: por una parte, estaban Sucre y sus partidarios; es decir, el Gobierno legalmente constituido, que calificaron a lo sucedido de una invasión, con todo y lo que eso conlleva. Por otra parte, estaban los alzados para quienes lo sucedido en abril de 1828 fue una revolución que estalló para liberar a Bolivia de la ocupación colombiana de la que se consideraba a Sucre como el principal cabecilla. Casimiro Olañeta formaba parte de esta última tendencia, así que hizo lo que estaba a su alcance para imponer esta versión.

En 1877, Gabriel René Moreno publicó sus “Documentos sobre el primer atentado del militarismo en Bolivia”, pero no en Bolivia, sino en Chile, advirtiendo que “el crimen frustráneo del 18 de abril permanece todavía para la posteridad envuelto en sombras. En Bolivia mismo es conocido apenas de bulto; porque también el bulto del suceso fue lo único que pudieron diseñar los documentos oficiales coetáneos…” (BNCH MC0049069, 247).

No era un simple artículo, sino que estaba acompañado de transcripciones de documentos que hacían varias revelaciones, desde uno que habla de la solidaridad demostrada por Tomás Frías y doña Josefa de Lizarazu con el ilustre herido (Ídem, 260), hasta la afirmación, todavía discutida hasta hoy, de que Sucre fue secuestrado en Ñucchu y permaneció en esa condición hasta la firma del tratado de Piquiza.

¿Cómo ocurrió esto? Detrás de la conspiración estaba Gamarra, que ya tenía listo un ejército de 6.000 hombres en Puno, seis meses antes de los sucesos de abril en Chuquisaca (Ídem, 269). Transcurridos 12 días del motín, Gamarra invadió Bolivia (Ídem, 271) y pasó hasta Oruro de donde siguió de largo con rumbo a Potosí, pero estableció su campamento en Siporo, hoy provincia Cornelio Saavedra.

Mientras eso ocurría, según esta versión, el coronel Pedro Blanco defeccionaba del ejército boliviano y se reunió en Macha con Gamarra:

“El coronel Blanco vino de Chichas, tanto por huir de una fuerza mayor que salió en su persecución de Potosí, cuanto por el designio de incorporarse con Gamarra, que ya se hallaba en Macha. Pasó por las orillas de esta ciudad (Potosí) sin entrar en ella, estando guarnecida con una pequeña fuerza de infantería. Después de unos 20 días volvió acompañado de un escuadrón más de peruanos, con banderolas peruanas; estos pasaron inmediatamente a Ñuccho y se llevaron preso al Gran Mariscal, hasta el campamento de Gamarra (en Siporo)” (MALLO, 1877: 272).

Ese testimonio está reforzado por lo que apareció en una publicación de la época:

“El coronel Blanco, dijo aquel Sr., á principios de mayo, desprendiéndose de Cotagaita, se dirigió á Chuquisaca. Hizo prisionero al Gran Mariscal presidente, en Ñuccho, donde se medicinaba; siguió su marcha hasta Macha. Allí recibió un refuerzo de un escuadrón peruano. Volvió con dirección a Potosí, y se hallaba hay en Puna, cuando pasaban las conferencias de Piquiza, reteniendo siempre a su prisionero” (AGUIRRE, 1871: 5).

Mediante una publicación de 50 páginas, los hijos de Pedro Blanco, Cleómedes y Federico, refutaron la publicación de Moreno y, pese a las pruebas exhibidas, rechazaron la versión de que su padre haya tomado prisionero a Sucre para retenerlo por espacio de dos meses. “El movimiento del 18 de abril (de 1828) fue una grande y verdadera revolución” (BC-F-01743, 1878: 2), publicaron.

Los Blanco señalan que hay pruebas de que Sucre preparó su mensaje a la nación en Chuquisaca y en este mismo dice que “se me arrancó bruscamente, el cuatro de julio, del retiro en que me curaba mis heridas” (Ídem, 15). A eso hay que agregar una publicación del Cóndor de Bolivia que dice que “el Presidente de la República salió desde el primero del corriente á una casa de campo distante cinco leguas de esta capital. Sus amigos se alegrarán de saber que va restableciéndose. El día once le han extraído del brazo la décima cuarta astilla de hueso, y aún creen los cirujanos que existe alguna más. Sin embargo, opinan que dentro de un mes sanarán las heridas” (CÓNDOR, 1828: 2).

La polémica duró hasta 2024, cuando se encontró la copia de la correspondencia de Galindo en el archivo, biblioteca y museo que está en Colcapirhua, Cochabamba, bajo la curaduría de su descendiente Arturo Galindo Grandchandt. Lo que demuestran estas cartas es que por lo menos en el periodo comprendido entre el 17 de junio al 5 de julio de 1828 hubo intenso movimiento de tropas en Bartolo (hoy Betanzos) y Chaquí, que están próximos a Siporo, así como en Puna y Potosí.

La fecha de 17 de junio corresponde a la primera carta que aparece en el folder que se conserva en la UMSA, ya que las cartas están numeradas y la que aparece primero tiene el número 323, lo que permite presumir que faltan 321.

En su contenido se da cuenta de asentamientos de tropas en los lugares referidos, además del reclutamiento de voluntarios, asignación de vestuario y otro tipo de movimientos que son normales en tiempo de guerra. Hay referencias explícitas a Pedro Blanco, considerándolo responsable del motín del 18 de abril de 1828 y, por lo tanto, un objetivo a destruir. En otras palabras, estos documentos refuerzan la versión de que Sucre fue secuestrado en Ñucchu y llevado a Siporo, donde se firmó el tratado de Piquiza el 6 de julio de 1828. Es necesario hacer notar que Piquiza está a muy corta distancia de Siporo. Si Antonio José de Sucre estuvo retenido en ese lugar, esa parece la razón por la que se haya elegido a Piquiza como lugar para la firma del tratado.

Ahora bien, si Sucre estuvo secuestrado en Siporo, eso justifica la presencia del Jefe de Estado Mayor, León Galindo, con sus tropas en la zona. Allí fue donde ejecutó la resistencia a la primera invasión peruana. Por razones que todavía deben estudiarse, Gamarra no pudo terminar la ocupación del territorio invadido y terminó firmando el tratado de Piquiza que, finalmente, fue humillante para Bolivia. A sabiendas de esto, encabezando sus tropas, Galindo optó por salir hacia Salta, a donde llegó el 24 de julio de 1828.

(*) Juan José Toro es fundador y socio de número de la Sociedad de Investigación Histórica de Potosí (SIHP).

Gráficos: Gentileza SIHP

Referencias:

- AGUIRRE, Miguel María. 1871. AJUSTE DE PIQUIZA EN 1828. Imprenta del Siglo. Cochabamba.

- BC-F-01743, Biblioteca Central de la UMSA. BLANCO, Federico y Cleómedes. Rectificaciones para la historia de Bolivia. Imprenta del Siglo. Cochabamba.

- BNCH MC0049069. MORENO del Rivero, Gabriel René. “Documentos sobre el primer atentado del militarismo en Bolivia”. En REVISTA CHILENA. Tomo IX. Jacinto Núñez, editor. Imprenta de la República. Santiago. 1877. pp. 246-288.

- MALLO, Jorge. “Apuntes sobre la connivencia del general Blanco y los demás incidentes al mismo respecto”. En BNCH MC0049069.

https://www.vision360.bo/noticias/2024/08/05/9540-el-secuestro-del-mariscal-de-ayacucho