By Esther Mamani, Vision 360:

Research

In Bolivian society, the work of grandmothers in raising and caring for their grandchildren is a widespread and overlooked practice because it entails a moral and physical burden as well as an economic contribution that is neither recognized nor valued. Specialists emphasize that the right to a dignified old age for elderly women is an urgent and necessary debate.

Luz with her two grandchildren on a recreational trip. Photo: Courtesy of Luz.

Every morning, at six o’clock sharp, Luz wakes up before her alarm goes off. At this hour, the cold intensifies in the city of El Alto, Bolivia, where she lives with her two grandchildren, aged six and eight, her mother, and her daughter, who spends most of the day working. Soon, the hustle of caring for her grandchildren will help her warm up.

After getting out of bed, Luz (name changed) dresses her grandchildren, gives them breakfast, and checks that all their materials are in their backpacks. She combines her passion for law with being a grandmother. She says that taking care of her grandchildren makes her feel young, fills her with energy and pride, but at the same time, she acknowledges, it involves dealing with daily stress and personal sacrifices.

Luz is one of many Bolivian grandmothers who dedicate a significant part of their time to caring for their grandchildren without receiving any economic compensation for all the tasks it entails. This is because caregiving work in the country remains largely invisible, and in the case of grandmothers, it is normalized, leading to caregiving being a never-ending job, even into old age.

Some grandmothers take on this responsibility because their sons or daughters work, while others are compelled to do so due to their absence, whether from family abandonment, emigration in search of better opportunities, death, or, in the case of women, being victims of femicide.

In Luz’s case, it is because her daughter and son-in-law work all day. “So, I’m the one in charge of my grandchildren,” she explains.

She is responsible for taking them to and picking them up from school and also has lunch with them. While the children do their schoolwork in the afternoon, she returns to her job, which is about 15 minutes by car from her house. In her absence, her 82-year-old mother also helps care for the little ones, staying with them until about seven in the evening when Luz returns home.

Researcher Carol Gilligan, in her text The Ethics of Care Thinks the Political, argues that the patriarchal system “imposes on women the role of ‘compulsive caregivers,’ leading to self-silencing and the sacrifice of their own needs.” It is a chain through time where, regardless of age, women continue to care.

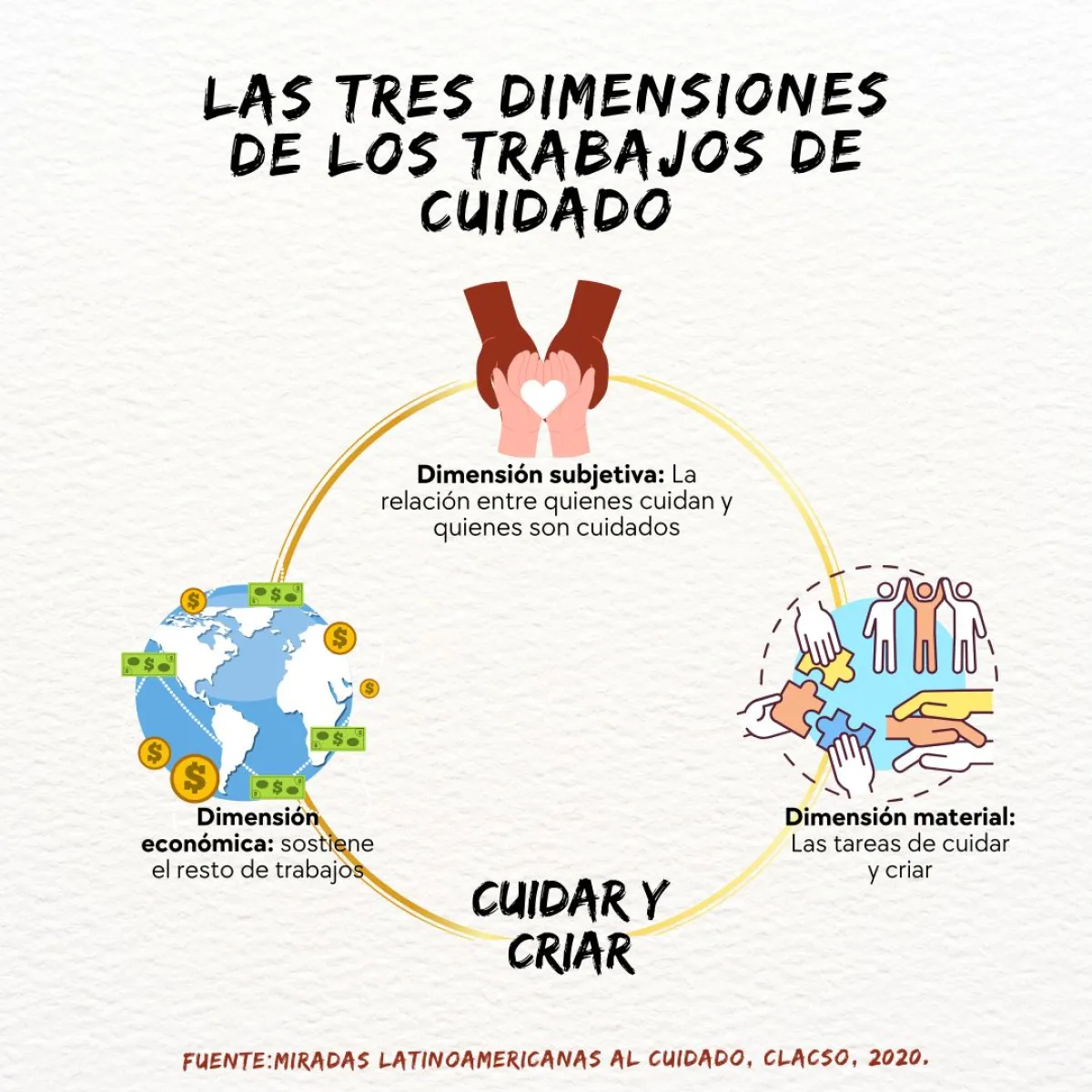

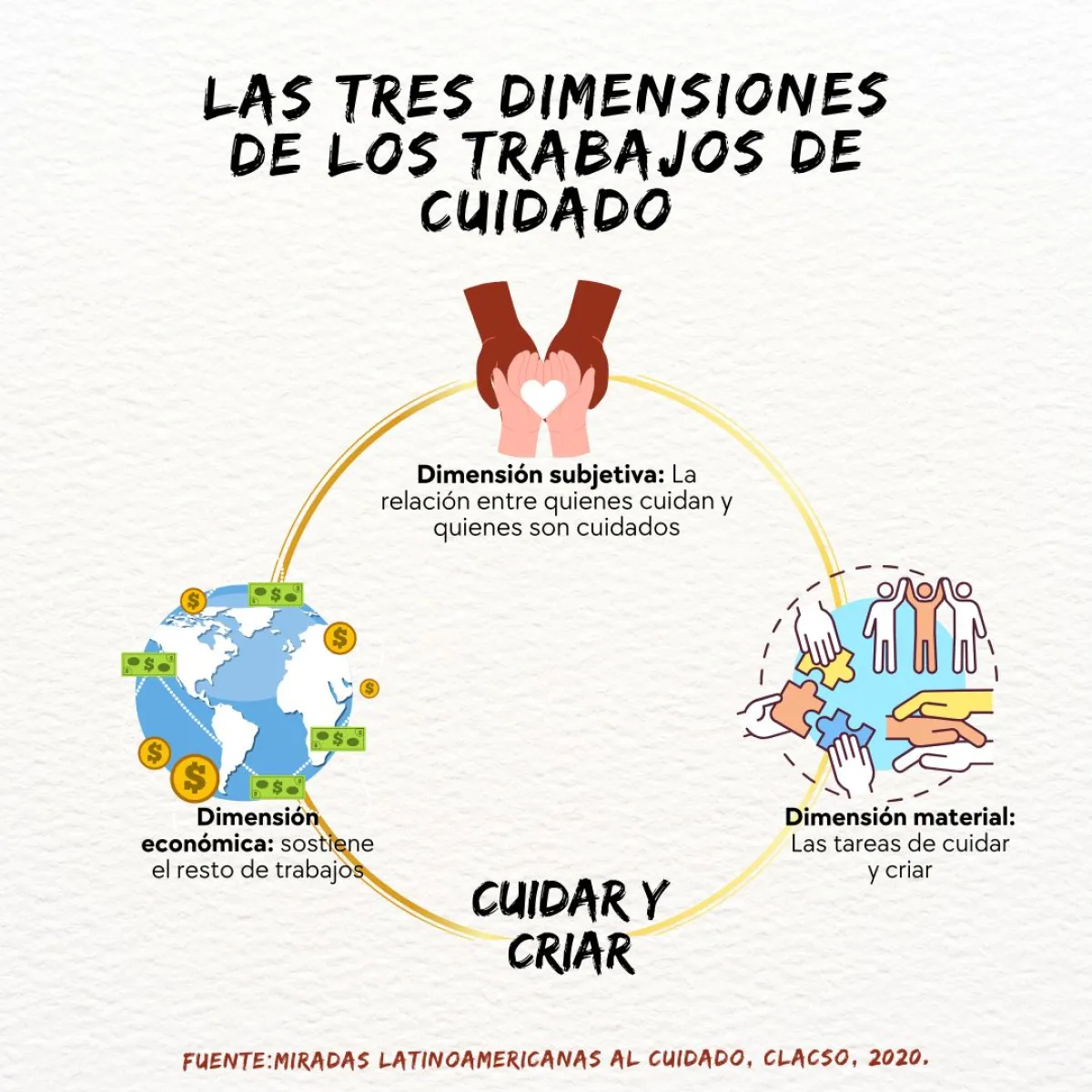

For other feminist researchers, the naturalization of caregiving work is justified by the affection grandmothers have for their grandchildren. Uruguayan sociologist Karina Batthyany states that this occurs because caregiving involves three dimensions: the economic, the material, and “a more subjective dimension.” The latter is “the relationship between caregivers and those cared for in terms of sensations and emotions at play,” she explains in an interview about the text Latin American Perspectives on Caregiving.

Caregiving, a Job

Claudia Arce, researcher and member of the National Care Platform in Bolivia, emphasizes the need to widely disseminate that caregiving is unpaid, undervalued labor without which people could not perform their other tasks.

“This is deeply ingrained in the lives and bodies of women. The first step is to recognize that raising and caring is work,” explains the expert, who was part of the effort in Cochabamba to approve the first Municipal Law on Shared Responsibility in Unpaid Care Work for Equal Opportunities.

Although the debate is emerging, many people outside feminist or gender circles also understand caregiving as labor, including Luz’s friends. “Your daughter should pay you a salary!” “You have the right to enjoy your time!” “It’s her responsibility, not yours!” are some of the remarks they frequently share with her.

If not for Luz, the parents of her grandchildren would need to find a daycare or hire a personal caregiver, which is not feasible due to the economic crisis facing the country.

Luz’s contributions to her household are highly valued by her daughter, who describes her as a fundamental pillar of their home. “She takes on responsibilities that I should handle but can’t because I’m working. She has taught my children so much—she talks to them, cares for them, and they’re used to her. This is temporary; I work a lot now, and my mom helps me tremendously because of that,” Luz’s daughter explains.

Karina Batthyany, executive director of the Latin American Council of Social Sciences, states that “the unequal distribution of caregiving responsibilities is a clear expression of patriarchal structures that normalize caregiving as a female duty.” This exclusion, she explains, reinforces gender stereotypes that perpetuate the idea of caregiving as inherently feminine, leaving women with an invisible and unpaid workload while men remain distant from these tasks.

Other caregiving grandmothers look after grandchildren who have been abandoned or whose parents have migrated in search of better opportunities elsewhere. “There are grandmothers caring for four, five, or even 10 grandchildren, and they don’t have the money to feed them. Many can’t even read or write,” Luz points out.

The situation for most elderly women in Bolivia is precarious, far from the dignified old age that entails respect for their rights, access to leisure activities, and adequate and timely healthcare, highlights a recent study by the Caritas Bolivia Social Pastoral Network.

“It is urgent to understand that caregiving is a collective responsibility, so they can enjoy a dignified old age, free from silent sacrifices,” reflects María Achá of Caritas Bolivia Social Pastoral.

Absent Parents, Present Grandmothers

Sofía and her granddaughter at her food stall in a central street of La Paz, Bolivia. Photo: Esther Mamani

Doña Sofía (name changed), an Aymara woman of 61 years, has spent the past 12 years being both a mother and grandmother. Her life took an unexpected turn when her son arrived one day holding a one-year-old girl and announced that the child’s mother, Sofía’s daughter-in-law, had passed away.

“Oh no, what am I going to do now?” Doña Sofía asked herself. Amid tears, she begged her son not to leave, but he ultimately fled, leaving the full responsibility for his daughter to his aging parents.

Although precise statistics on the number of fathers abandoning their children are unavailable, data from the National Institute of Statistics (INE) shows that, as of 2017, 45.5% of households in Bolivia were led solely by women as heads of the family.

A report by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) links child abandonment in Bolivia to the absence of paternal figures. It reveals that 80% of children in care centers have known relatives, yet only 58% receive visits from their parents. The analysis, made public in 2022, reflects statistics from the 22 years preceding its release.

Sofía’s granddaughter is among these statistics, having been orphaned and abandoned by her father. All they know about him is that he went to Brazil. He has not contacted either his mother or daughter, who remain in La Paz, Bolivia.

Terrified but resolute, Doña Sofía chose to care for the little girl. That first night, the baby snuggled into her arms as if she instinctively knew she had found a new home. “She was so calm, didn’t cry or fuss. She has always been easygoing. From that day, I’ve raised her as my own daughter,” Sofía recalls. Today, they are inseparable.

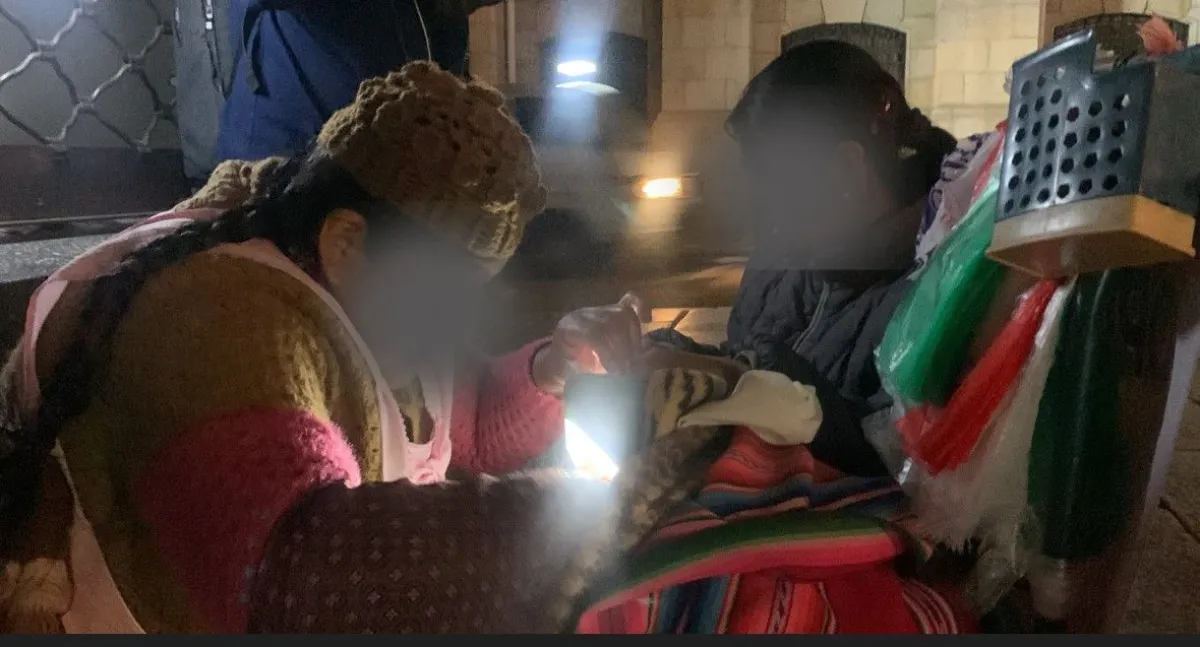

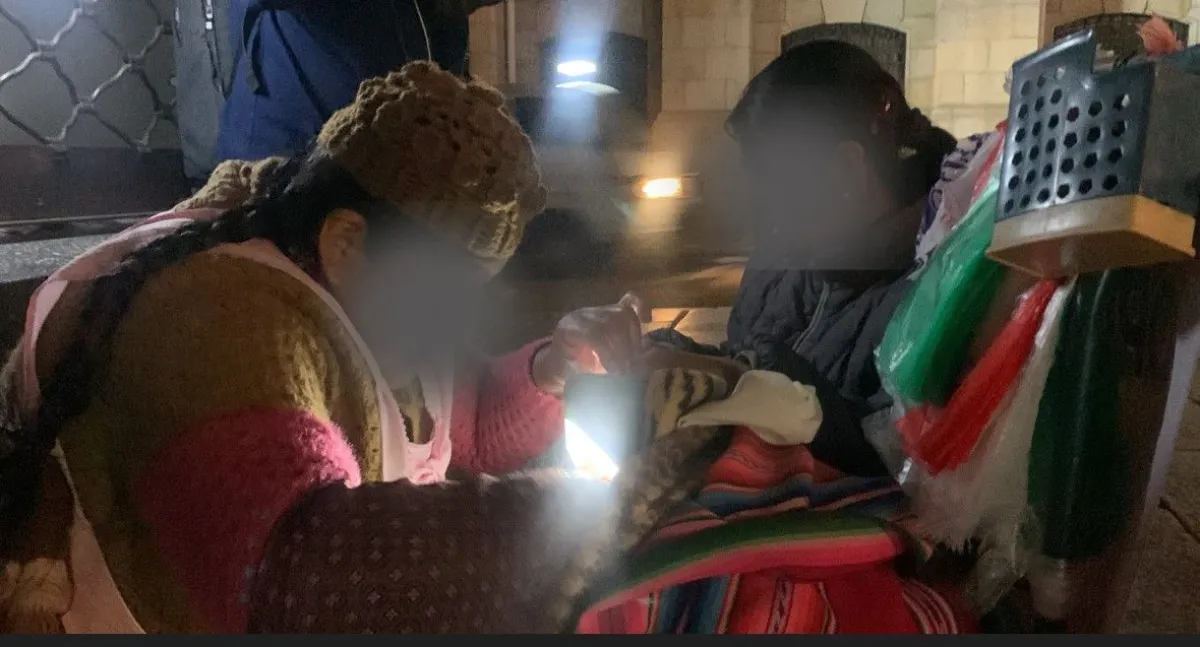

To cover the costs of raising her new “daughter,” Doña Sofía began selling noodle soups (noodles with peanuts, silpancho, flour tortillas, eggs, or cheese)—a job she continues to this day. Each night, both grandmother and granddaughter brave the cold streets of La Paz to sell their food.

“How could I leave her alone? I can’t just lie in bed while my grandma is out in the cold. She’s my mom, and I want to give her everything she deserves,” the teenager says when asked why she accompanies her grandmother.

Like Sofía, thousands of Bolivian women are heads of single-parent households. Women of all ages, including those in their senior years, make up 82% of these households, according to the study Families in Transition: Changes in Bolivian Families Between 2002 and 2017, conducted by the Socioeconomic Research Institute (IISEC) of the Bolivian Catholic University (UCB) and the Fundación Jubileo.

Each day, Sofía goes shopping early in the morning and returns home around 10 a.m. while her granddaughter attends school. In the afternoon, the two work together: Sofía cooks, and her granddaughter does her schoolwork. Around six in the evening, they head downtown carrying the food and supplies for their stall, where they sell until about 10 p.m.

Mary dreams of attending university and securing a career to provide her “mom” with a dignified old age. For now, she contributes by earning good grades at school and helping with the business, managing payments for the noodle soups and organizing napkins and stools for their customers.

Grandmothers, when in charge of raising their grandchildren, take on many roles. Like her, other older women experience the situation of being the head of their households.

According to the Post-Census Study on the Elderly in 2012, conducted by the National Institute of Statistics, in rural areas, 24.3% of households are headed by elderly adults, while in urban areas, this percentage drops to 15.2%.

This is not the only study; others show that caregiving, raising children, and working fall heavily on grandmothers. Six out of ten women aged 60 and older dedicate up to five hours a day to caregiving, according to OXFAM’s report “Tiempo para cuidar” in Bolivia.

In Sofia’s case, since taking full responsibility for raising her granddaughter, she dedicates many more hours to her care, not only as a grandmother but also legally as a mother. “The notary told me to recognize (register her) as my daughter since we didn’t know how to get her birth certificate. My husband and I legally recognized her,” she recalls while continuing to sell food.

In this family, food sales sustain their economy by dividing tasks. “My husband goes even though he’s sick. He got COVID, but he takes care of her studies,” she says.

While the grandmother shares her story, the teenager keeps her eyes on her, and when a customer arrives, they work together seamlessly, exchanging instructions with just a glance. A municipal guard approaches to ask them to leave, and in seconds, they pack up everything to leave. “I’m actually done (with the food),” Sofia says as she bids goodbye.

Aging to Rest

Miriam Chávez, a member of the Casa de la Mujer in Santa Cruz, explains that the roles society imposes on women regarding family care are constraints. “We end up being reproducers of the patriarchal system because it’s unpaid work, and the patriarchal system doesn’t say anything. It’s a way of perpetuating itself with a large subordinated population that we women are,” she argues.

For the activist, this demonstrates a lack of social justice where these women are subjected to unpaid and socially devalued tasks. Therefore, it is crucial that the burden is not invisibilized, that caregiving is not seen as a natural mandate for women, but as a task that needs support, redistribution, and recognition, the expert emphasizes.

According to the study “Situation and Differentiated Characteristics of Urban and Rural Aging in Bolivia” from 2019, Bolivia’s population growth rate shows that the segment with the most growth is the population aged 60 and older, as from 2001 to 2012, the population under 14 years of age decreased by -0.1%.

“In Bolivia, older adults generally live within extended families, and there is still a strong sense of collaboration between parents and children, though cases of domestic violence are increasing. Grandmothers help with the care of grandchildren, and those who care for dependent elderly people are daughters,” says the study.

The voices of women like Luz and Sofia demonstrate that these family ties involve exhaustion and postponed dreams. They don’t seek rewards, as they explain.

“The State must fulfill public policies that recognize their role and offer alternatives for shared and sustained caregiving,” explains Claudia Arce from the Care Platform.

Caregiving and Violence

Other grandmothers who care for grandchildren face intertwined vulnerabilities. Some even consider filing complaints, though no statistics or data exist on complaints regarding the impositions of caregiving and raising grandchildren.

Older adults may suffer other abuses such as the withholding of their pension incomes or the stripping of their property. The Plurinational Integrated Justice Services (SIJPLU), under the Ministry of Justice, reported that during the first half of 2024, they provided legal assistance to 4,461 elderly people (2,510 women and 1,951 men). In 2023, they assisted 4,612 people, all cases related to the violation of rights of this population.

In this context, Bolivian grandmothers are not only raising their grandchildren but are holding up the country because, without them, the fate of many minors would be uncertain or, alternatively, someone would have to pay for these services in daycare centers or with personal caregivers.

(*) This report was produced by the Feminist Journalism Network with funding from the Bolivia Women’s Fund – Apthapi Jopueti.

Por Esther Mamani, Vision 360:

Investigación

En la sociedad boliviana el trabajo de las abuelas en la crianza y cuidado de nietos y nietas es una práctica extendida e invisibilizada porque implica una carga moral y física y un aporte económico que no se reconoce ni valora. El derecho a una vejez digna de mujeres de la tercera edad es un debate urgente y necesario, resaltan las especialistas.

Luz junto a sus dos nietos en un viaje de recreación. Foto: Gentileza de Luz.

Todas las mañanas, a las seis en punto, Luz despierta antes de que suene la alarma. A esta hora el frío recrudece en la ciudad de El Alto, Bolivia, donde vive con sus dos nietos de seis y ocho años, su madre y su hija, quien pasa la mayor parte del día trabajando. Pronto, el ajetreo de cuidar a sus nietos le ayudará a entrar en calor.

Tras levantarse de la cama, Luz (nombre cambiado) cambia a sus nietos, les da de desayunar y revisa que en sus mochilas estén todos sus materiales. Ella combina su pasión por la abogacía con ser abuela. Ella dice que cuidar a sus nietos le hace sentir joven, le llena de energía y orgullo, pero al mismo tiempo, reconoce, que le implica lidiar con el estrés y las renuncias personales del día a día.

Luz es una de las muchas abuelas bolivianas que dedican gran parte de su tiempo al cuidado de sus nietos sin recibir remuneración económica por todas las tareas que eso implica. Esto se debe a que en el país aún el trabajo de cuidados, en general, sigue siendo invisibilizado y, en el caso de las abuelas en particular es naturalizado, lo que ocasiona que criar y cuidar sea un trabajo de nunca acabar, incluso durante la vejez.

Algunas abuelas asumen esta responsabilidad porque sus hijos o hijas trabajan, mientras que en otros casos se ven obligadas a hacerlo ante la ausencia de éstos, ya sea por abandono familiar, emigración en busca de mejores oportunidades, fallecimiento o, en el caso de las mujeres, por haber sido víctimas de feminicidio.

En el caso de Luz es porque su hija y nuero trabajan todo el día. “Entonces, soy yo la que está a cargo de mis nietos”, explica.

Ella es la encargada de llevarlos y recogerlos de la escuela, y además almuerza con ellos. Mientras los niños realizan sus tareas escolares durante la tarde, ella regresa a su trabajo, que está a unos 15 minutos en auto desde su casa. En su ausencia, su madre, de 82 años, también es parte del cuidado de los pequeños pues se queda con ambos aproximadamente hasta las siete de la noche cuando Luz retorna.

La investigadora Carol Gilligan, en el texto La ética del cuidado piensa lo político, afirma que el sistema patriarcal “impone en las mujeres el rol de ‘cuidadoras compulsivas’, lo cual lleva a la auto-silenciación y al sacrificio de sus propias necesidades”. Es una cadena en el tiempo donde sin importar la edad las mujeres siguen cuidando.

Para otras investigadoras feministas la naturalización de los trabajos de cuidado se justifica con el cariño que se tiene, en el caso de las abuelas, a las o los nietas. La socióloga uruguaya Karina Batthyany afirma que esto sucede, porque en el cuidado actúan tres dimensiones: la económica, la dimensión material y “una dimensión más subjetiva. Esta última es “la relación entre quienes cuidan y quienes son cuidados en términos de sensaciones y sentimientos que se ponen en juego”, afirma en una entrevista sobre el texto Miradas latinoamericanas a los cuidados.

Los cuidados, un trabajo

Claudia Arce, investigadora y parte de la Plataforma Nacional de Cuidados en Bolivia asegura que es preciso difundir de forma masiva que los trabajos de cuidado son trabajos no pagados, no valorados y que sin ellos las personas no podrían cumplir sus otras tareas.

“Esto está muy naturalizado en las vidas y cuerpos de las mujeres. El primer paso es dar cuenta que criar y cuidar es un trabajo”, explica la experta, quien en la capital de Cochabamba fue parte del trabajo para la aprobación de la primera Ley Municipal de Corresponsabilidad en el Trabajo del Cuidado No Remunerado para la Igualdad de Oportunidades.

Si bien es un debate emergente, hay muchas personas fuera de los entornos feministas o de género que también entienden el cuidado como un trabajo, por ejemplo las amigas de Luz. “¡Que tu hija te pague un sueldo!”, “¡Tienes derecho a disfrutar tu tiempo!”, “¡Es su responsabilidad, no la tuya!” son algunas de las frases que le dicen constantemente.

De no ser por ella la madre y padre de sus nietos tendrían que buscar un centro infantil o pagar por una cuidadora personal, pero debido a la crisis económica que enfrenta el país, esto no es posible

El aporte que Luz hace en su casa, es valorado por su hija, quien la describe como un pilar fundamental de su hogar. “Cubre cosas que yo debería asumir y no lo hago ya que estoy trabajando. Ella les ha enseñado tanto (a mis hijos), les habla, les cuida y están acostumbrados a ella. Esto es temporal, ahora trabajo mucho y mi mamá me apoya muchísimo por eso”, detalla la hija de Luz.

Karina Batthyany, directora ejecutiva del Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales, afirma que “la asignación desigual de los trabajos de cuidado es una expresión clara de las estructuras patriarcales que naturalizan el cuidado como responsabilidad femenina”. Esta exclusión, explica, refuerza los estereotipos de género que perpetúan la idea de que los cuidados son inherentemente femeninos, dejando a las mujeres con una carga de trabajo invisible y no remunerada, mientras que los hombres se mantienen distantes de estas.

Otras abuelas cuidadoras están con nietos y nietas abandonadas o cuyos padres y madres han migrado en busca de mejores oportunidades en otros territorios. “Hay abuelas que cuidan a cuatro, cinco o hasta 10 nietos, y no tienen dinero para alimentarlos. Muchas ni siquiera saben leer ni escribir”, comenta Luz .

La situación de la mayoría de las mujeres adultas mayores en Bolivia es precaria y está lejos de tener una vejez digna que implica el respeto a sus derechos, tener acceso a actividades de ocio y a servicios de salud adecuados y oportunos, resalta un estudio reciente de la Red de Pastoral Social Cáritas Bolivia.

“Es urgente que entendamos que cuidar es una responsabilidad colectiva, para que puedan disfrutar de una vejez digna, libre de sacrificios silenciosos”, reflexiona María Achá de la Pastoral Social Caritas Bolivia.

Padres ausentes, abuelas presentes

Doña Sofía (nombre cambiado), una mujer aymara de 61 años, lleva 12 años siendo madre y abuela a la vez. Su vida dio un giro inesperado cuando su hijo llegó un día a casa con una niña de un año en brazos y con la noticia de que la mamá, nuera de Sofia, había muerto.

“Ay no, ¿qué voy a hacer ahora?”, se preguntaba Doña Sofia y entre sollozos rogó a su hijo que no se vaya, pero finalmente el progenitor huyó dejando toda responsabilidad de su hija a su mamá y papá, ambos de la tercera edad.

Aunque no se cuenta con una estadística precisa del número de padres que abandonan a sus hijos, datos del Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE) muestran que, hasta 2017, el 45,5% de los hogares estaban a cargo únicamente de mujeres en calidad de madres.

Un informe del Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia (UNICEF) asegura que el abandono infantil en Bolivia está relacionado con la ausencia de la figura paterna. El 80% de los niños en centros de acogida tienen familiares conocidos, pero solo el 58% recibe visitas de sus padres. El análisis se hizo público en 2022 con estadísticas de los últimos 22 años antes de su publicación.

La nieta de Sofía es parte de esas estadísticas al haber quedado huérfana y sido abandonada por su padre. Lo único que saben de él es que fue a Brasil. No se ha comunicado con su madre ni hija que están en La Paz, Bolivia.

Esta abuela estaba aterrorizada y eligió en esa situación cuidar a la pequeña. Esa primera noche la bebé se acurrucó en sus brazos como si supiera que había encontrado un nuevo hogar. “Bien tranquilita estaba, no ha llorado, no ha molestado. Siempre ha sido tranquila. La he criado como mi hija desde ese día”, recuerda. Hoy, ambas son inseparables.

Para costear los gastos de la nueva hija, doña Sofía empezó a vender sopitas de fideo (fideo con maní, silpancho, tortillas de harina, huevo o queso) y es un trabajo que aún continúa. Cada noche ambas se enfrentan al frío paceño vendiendo en la calle.

“Como le voy a dejar sola, yo no puedo estar en mi cuarto echada de panza mientras mi abuela está haciéndose soplar con el frío. Ella es mi mamá, y yo quiero darle todo lo que se merece”, afirma la adolescente a la pregunta de ¿por qué acompaña a su abuela?

Como Sofía, miles de mujeres bolivianas son jefas de hogares monoparentales. Mujeres de diferentes edades incluyendo a las de la tercera edad, representan el 82%, según con el estudio Familias en transición: Cambios en las familias bolivianas entre 2002 y 2017, realizado por el Instituto de Investigaciones Socio-económicas (IISEC) de las Universidad Católica Boliviana (UCB) y la Fundación Jubileo.

Diariamente Sofia hace las compras muy temprano y retorna a casa cerca de las 10 de la mañana mientras su nieta asiste a la escuela. Por la tarde ambas trabajan: la abuela cocinando, la nieta cumpliendo sus deberes escolares. Cerca a las seis de la tarde bajan al centro de la ciudad cargando la comida y todos los enseres necesarios para la venta que se extiende hasta las 10 de la noche en promedio.

Mary sueña con estudiar una carrera universitaria y trabajar para darle una vejez digna a su mamá. Por el momento retribuye con buenas calificaciones en la escuela y siendo la responsable de los cobros de las sopitas de fideo, además de acomodar las servilletas y los taburetes para los comensales.

La abuela, al estar a cargo de la crianza, cumple muchas tareas. Como ella, otras mujeres de la tercera edad viven esta situación de estar en la jefatura de los hogares.

Según el Estudio Post Censal de Adulto Mayor de 2012, elaborado por el Instituto Nacional de Estadística, en el área rural el 24,3% de los hogares está a cargo de adultos o adultas mayores, en las ciudades este porcentaje se reduce al 15,2%.

No es el único estudio, hay otros que señalan que demuestran que las tareas de cuidado, crianza y trabajo están en la espalda de las abuelas. Seis de cada 10 mujeres de 60 años y más dedican hasta cinco horas diarias al cuidado según el informe “Tiempo para cuidar” de OXFAM en Bolivia.

En el caso de Sofía, desde que asumió la crianza total de su nieta, dedicó muchas más horas a su cuidado y no solo como su abuela, sino legalmente como su madre. “El notario me dijo que le reconozca (inscriba como hija suya) no más porqué no sabíamos cómo hacer para sacar su certificado de nacimiento. Le hemos reconocido (a su nieta) con mi esposo entonces”, recuerda mientras continúa la venta de los alimentos.

En esta familia, la venta de comida sostiene su economía dividiendo tareas.. “Mi esposo va, aun cuando (está) enfermito. Se ha enfermado de Covid, pero se encarga de todo lo que son sus estudios”, cuenta.

Mientras la abuela brinda su relato, la adolescente no deja de mirarla y cuando llega un comensal ambas trabajan en una amalgama en la que con solo mirarse se dan instrucciones. Un guardia municipal se acerca para pedirles que se vayan y en cuestión de segundos guardan todo para retirarse. “Ya he acabado más bien (la comida)”, cierra Sofía y se despide.

Envejecer para descansar

Miriam Chávez, integrante de la Casa de la Mujer de Santa Cruz, explica que los roles que la sociedad impone a la mujer sobre el cuidado de la familia son imposiciones. “Terminamos siendo reproductoras del sistema patriarcal porque es un trabajo gratuito y el sistema patriarcal no dice nada. Es la forma de perpetuarse como sistema con una gran población subordinada que somos las mujeres”, afirma.

Para la activista esto demuestra una falta de justicia social donde estas mujeres están sometidas a tareas no remuneradas y desvalorizadas socialmente. Por ello es crucial que la carga no quede invisibilizada, que la labor de cuidado no se vea como un mandato natural para las mujeres, sino como una tarea que necesita apoyo, redistribución y reconocimiento, resalta la experta.

Según el estudio “Situación, características diferenciadas del envejecimiento urbano y rural en Bolivia” de 2019, la tasa de crecimiento de la población boliviana muestra que el segmento poblacional que más crece es el de personas mayores de 60 años, pues desde el año 2001 al 2012, la población menor de 14 años decreció en un -0,1%.

“En Bolivia las personas mayores en general viven en el seno de familias ampliadas y todavía existe un fuerte sentido de colaboración entre padres e hijos, aunque aumentan los casos de maltrato familiar. Las abuelas ayudan con el cuidado de los nietos y quienes cuidan a personas mayores dependientes son las hijas mujeres”, dice el estudio.

Las voces de mujeres como Luz y Sofía demuestran que esos lazos familiares implican cansancio y anhelos postergados. Ellas no buscan recompensas según explican.

“El Estado debe cumplir con políticas públicas que reconozcan su papel y que ofrezcan alternativas para que el cuidado sea compartido y sostenido”, explica Claudia Arce de la Plataforma de Cuidados.

Cuidados y violencia

Otras abuelas cuidadoras enfrentan vulnerabilidades entrelazadas. Algunas llegan a plantear denuncias aunque no se tienen estadísticas ni datos de denuncias por imposiciones del trabajo de cuidado y crianza de nietos o nietas.

Las personas de la tercera edad pueden sufrir otros abusos como la retención de sus rentas de jubilación o despojo de sus propiedades. Los Servicios Integrales de Justicia Plurinacional (SIJPLU), dependiente del MInisterio de Justicia, reportan que durante el primer semestre de 2024, brindaron asistencia jurídica a 4.461 personas adultas mayores (2.510 a mujeres y 1.951 a varones). En 2023 fueron 4.612. Todos los casos relacionados a la vulneración de derechos contra esta población.

En este contexto, las abuelas bolivianas no solo están criando a sus nietos y nietas, sino que están sosteniendo al país porque sin ellas, el destino de decenas de menores sería incierto o de lo contrario alguien tendría que pagar para esos cuidados en centros infantiles o con cuidadoras personales.

(*) Este reportaje fue realizado por la Red de Periodismo Feminista con la subvención del Fondo de Mujeres Bolivia – Apthapi Jopueti.