Correo del Sur:

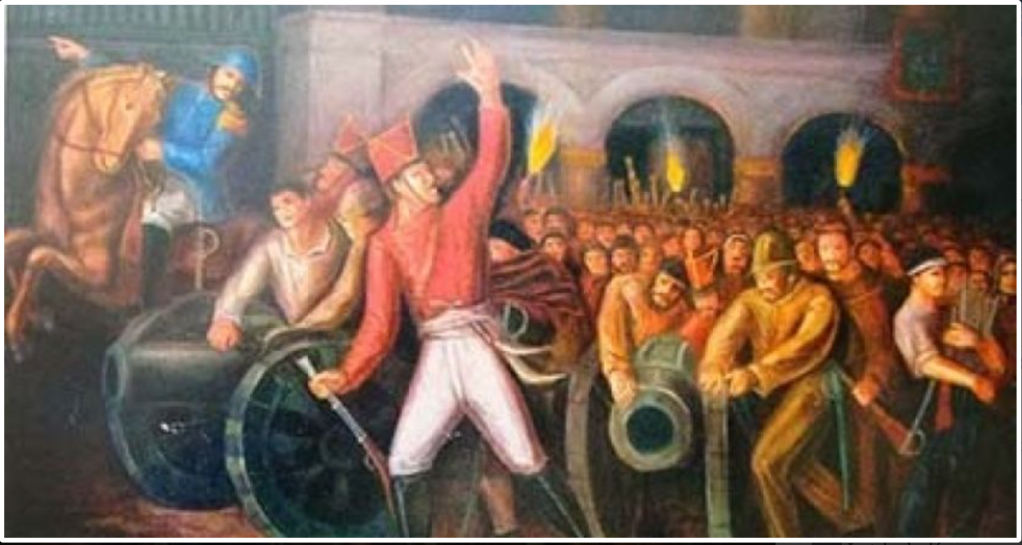

Una obra de arte que ilustra la gesta libertaria de mayo. INTERNET

May 25, 1809, the day hard liquor was drunk with gunpowder

Chuquisaca commemorated the 214th anniversary of events that lasted at least one more day and that constituted the First Cry for Freedom

This May 25, 2023 was Thursday, just like 214 years ago, when the First Cry for Freedom of Latin America was given in La Plata, today Sucre.

Estanislao Just Lleó, the historian who dedicated his life to studying this feat, makes numerous revelations about the events of May 25, 1809 in La Plata, today Sucre, in his book “Beginnings of independence in Upper Peru.”

The political scientist Franz Flores especially highlighted one on his social networks and in an interview with Correo del Sur Radio (minute 13):

“Meanwhile in the square the cries of treason, and cheers for the republic accompanied the insults to the president. The mutinous mob led by a group of Creoles, among whom we could point out the Zudañez and Lemoines, Malavía, Monteagudo, Toro, Miranda, Sivilat, etc, etc., became more and more excited, thanks to the hard liquor that was mixed with gunpowder. it was distributed to them, and to the money they received from some of those leaders for shouting and cheers for Fernando VII and death to the government”.

From that fragment, Flores emphasized the participation of the people in the First Cry for Freedom, often presented only as a revolution of Creole “doctors of Charcas.”

“Following Octavio Paz, in one of his ‘Corriente alterna’ essays, we will say that in May 1809 there were two parallel social processes: revolution and revolt. The first one thought and planned by the charquina middle class, made up of the judges and lawyers of the San Francisco Xavier University, with a clear ideology, objectives and strategy and, where the phrase, long live Fernando VII! serves as a valid pretext for the achievement of their political ambitions and, on the other hand, a popular and plebeian revolt, which sees President Pizarro as a traitor and abusive and who, in the chaos of the events of May 25, an occasion to trample on and execrate the symbols of power that humiliates and postpones them”, questioned from the canteens and anonymous lampoons, he manifests.

He thus called to honor, for example, the Quitacapas, also a leader of those days.

The revolt of May 25, 1809 spread to at least the 26th; Between the two days, Jaime de Zudáñez was released and the president of the Royal Audience of Charcas, Ramón García Pizarro, was imprisoned, with a balance of more than 30 deaths, according to historians.

25 de mayo de 1809, el día que se bebió aguardiente con pólvora

Chuquisaca conmemoró el 214 aniversario de unos hechos que se extendieron al menos un día más y que constituyeron el Primer Grito de Libertad

Este 25 de mayo de 2023 fue jueves, tal como hace 214 años, cuando se dio el Primer Grito de Libertad de América Latina en La Plata, hoy Sucre.

Estanislao Just Lleó, el historiador que dedicó su vida a estudiar esta gesta, hace numerosas revelaciones sobre los acontecimientos del 25 de mayo de 1809 en La Plata, hoy Sucre, en su libro “Comienzos de la independencia en el Alto Perú”.

El politólogo Franz Flores destacó especialmente uno en sus redes sociales y en una entrevista con Correo del Sur Radio (minuto 13):

“Mientras tanto en la plaza los gritos de traición, y vivas de la república acompañaban los insultos al presidente. La plebe amotinada dirigida por un grupo de criollos entre los que se podían señalar a los Zudañez y Lemoines, Malavía, Monteagudo, Toro, Miranda, Sivilat, etc, etc.. se iba cada vez excitando más, gracias al aguardiente que mezclado con pólvora se les iba repartiendo, y al dinero que recibían de algunos de aquellos dirigentes por dar gritos y vivas a Fernando VII y mueras al gobierno”.

A partir de ese fragmento, Flores enfatizó en la participación del pueblo en el Primer Grito de Libertad, muchas veces presentado solo como una revolución de criollos “doctores de Charcas”.

“Siguiendo a Octavio Paz, en uno de sus ensayos de ‘Corriente alterna’, diremos que en mayo de 1809 hay dos procesos sociales paralelos: revolución y revuelta. La primera pensada y planificada por la clase media charquina, compuesta por los oidores y abogados de la Universidad San Francisco Xavier, con ideología, objetivos y estrategia clara y, donde la frase, ¡viva Fernando VII! sirve como válido pretexto para el logro de sus ambiciones políticas y, por otra parte, una revuelta, popular y plebeya, que ve en el presidente Pizarro a un traidor y a un abusivo y que, en el caos de los sucesos del 25 de mayo, una ocasión para pisotear y execrar los símbolos de poder que los humilla y posterga”, cuestionado desde las cantinas y pasquines anónimos, manifiesta.

Llamó así a honrar, por ejemplo, al Quitacapas, también líder de aquellas jornadas.

La revuelta del 25 de mayo de 1809 se extendió al menos al 26; entre ambos días, se liberó a Jaime de Zudáñez y se encarceló al presidente de la Real Audiencia de Charcas, Ramón García Pizarro, con un saldo de más de 30 muertos, según refieren los historiadores.